In recent years there has been a proliferation of non-partisan groups aiming to promote awareness around citizenship and electoral rights and rules. Looking at evidence from recent general elections, Luke Temple and Ana Ines Langer assess the importance of this activism and contemplate its future.

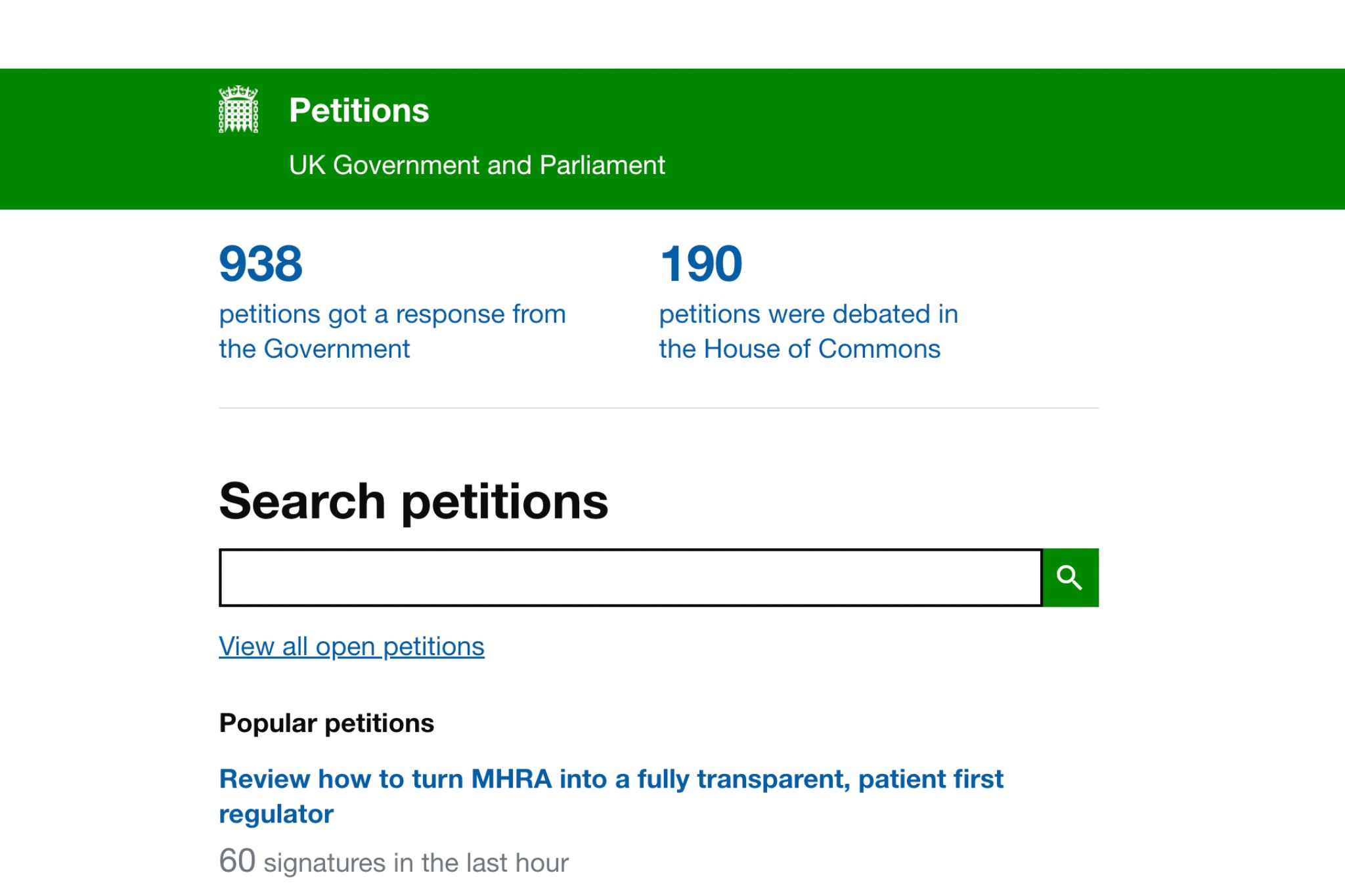

During the 2017 and 2019 UK general elections, a vibrant space of “democracy activism” emerged, with citizen groups campaigning on issues like voter information and advice, voter registration, vote swapping, government transparency, and electoral integrity. Although most campaigns were independent from political parties, in an era of low turnout, low levels of political trust and low numbers of people joining parties, even if citizen groups aim to be politically neutral there remains potential for them to influence election campaigns, and even outcomes.

We researched these groups through interviews, analysing websites and social media, and observing networking events to find out how this space of democracy activism was developing and to explore what barriers it faced.

Even if citizen groups aim to be politically neutral there remains potential for them to influence election campaigns, and even outcomes.

The space is small but complex, full of passionate and skilled activists. Organisations we spoke to didn’t fit into existing categories very well (such as pressure group, trade-union, charity, and so on), making them tricky to analyse. The space has many websites, Whatsapp and Facebook groups, social media accounts, email lists, apps, blogs, crowd-sourced documents and databases. But many campaigns are short-lived, leaving behind broken links, lapsed websites, out-of-date voter advice applications, and abandoned social media feeds. Especially outside of election time, it can be difficult to tell if a campaign or organisation is active. Overall, this can make it confusing to navigate from the outside.

Distinctive approaches

To try and get a handle on this complexity we analysed the space by focusing on different “approaches” (we used a strategic action field framework). We suggest three key approaches shape the space:

- Electioneering – mobilising voters and improving the impact of campaigning

- Social movement – thinking about long-term change and strategy

- Civic tech – using technology to solve social problems

By contrasting these three approaches we can shed light on some of the challenges that campaigners face.

The civic tech and social movement approaches are usually “positive-sum”, prioritising transparency, sharing resources, and collaborating, no matter who benefits. Their target is the citizen in a democracy. In contrast, for the electioneering approach citizens still matter – in terms of access to information, registration, and turnout – however, the citizen is now unavoidably a partisan voter. This is a “zero-sum” situation, especially under the UK’s voting system.

This leads to hard questions – do you make tools that potentially give an advantage to one party more than another? What if it benefits people you strongly disagree with? Can you uphold different values when an election is on, compared to the rest of the time? More than one activist described how this prompted a lot of ‘soul-searching’, but no easy answers.

Civic tech is synonymous with “hackathons”, short and focused events where the tech-savvy work to fix something, usually software related. They often put out experimental ideas in “beta” form to be tested by users. This approach can be fragmentary and work in quick bursts. However, the social movement approach is much more about laying groundwork to bring about long-term and lasting change. The electioneering approach is similar in some ways but must also adapt to the compressed and high-pressure window of an election. The rhythms of an election are powerful and hard to manage – this is amplified when all these different habits and ways of doing things are being combined across several organisations.

What the findings tell us

One consequence of the democracy activism space utilising digital technology in innovative ways is that the way groups (and campaigns) are organised varies widely. This was clear in activists’ language when it came to describing their own organisations, which were frequently tentatively described as “things” that “overlap” and are “messy”. This is exciting in many ways, but, with no obvious blueprint to work to, it can also make it difficult to effectively reach out, build relationships or just navigate the space. It is hard to know how everyone operates and where each organisation stands in relation to the other.

The activists we spoke to were highly skilled, but often their skillset was linked to one of the three approaches, meaning different types of work can get “siloed”. Research has identified a general growth in activists who – whilst principled and committed to particular causes – are less connected to specific organisations. These people tend to be “doers” and less so “joiners”. We frequently saw activists moving in and out of roles and across campaigns, undertaking “micro-actions” or “micro-volunteering”: providing niche, specific and small-scale contributions. People “drop in and out”, something that working digitally allows for, yet this was even the case for physical meet-ups. Even core activists in organisations might also be working across multiple projects elsewhere. This is greatly facilitated by digital technology but frequently necessary due to funding.

Funding challenges

How to fund an organisation raises questions around values as well as organisational structure: having fee-paying members (a rare choice amongst those we spoke to) requires different considerations than selling services or seeking grants from funders.

The unavoidable proximity to partisan politics also poses difficulties. Financing voter literacy can be seen as controversial, or it can be seen as a waste when an organisation is not advocating a partisan view. This is compounded by the waning general interest in citizen literacy during lulls in the electoral cycle.

Financing voter literacy can be seen as controversial, or it can be seen as a waste when an organisation is not advocating a partisan view.

Even capturing funding might not guarantee much long-term financial security. One activist explained how they were funded to prove the value of a project, which they did. Then the funder moved on. This leads to questions of how (and which) services can be provided in a sustainable way, and what role the state might play.

Regulation dilemmas

Whilst digital campaigning continues to be a headache for electoral regulation, in general UK elections can still be considered highly regulated affairs with tight spending limits. Inexperienced organisations are likely to struggle to navigate the complex regulation. Indeed, following recent elections the Electoral Commission conducted a number of investigations into non-party campaigners, in some cases resulting in fines. These were usually related to issues of accounting or auditing. While recognising the importance of restricting the influence of money in electoral campaigning, interviewees expressed fears that the complexity of rules would put people off campaigning, resulting in a “legal game” and “arms race” of powers being given to the Commission.

Digital technology – the lure of quick fixes

Digital technology does not necessarily cause the issues discussed so far, but it can amplify them. Emphasis on digital technology is unsurprisingly core to the civic tech approach – an interviewee linked it to a “build it, ship it, quick, make mistakes as you go” attitude which clashed with the longer-term messages required for campaigning and funding. At its most technocratic, it can come with a “one tool to save democracy” mentality, viewing voters as simply needing to be “nudged” by the right tool to vote “smarter”. This does not align well with tribal, emotional, or political identity approaches found in social movement and electoral campaigning.

Finally, we observed that for all the networking, organisational, and media power offered by digital technology, interviewees often noted a frustrating inability to really get any kind of sense of its impact. Many were limited to using website hits, which offer limited insight into the actual effect a campaign is having.

Looking ahead

Our research demonstrates how thinking through these issues using different approaches helps illuminate why sticking points may have arisen. Moving forward, engagement with political elites will likely be important as activists raised a key question – in a democracy, what part of this activity should be supported by the state?

This article draws on research funded by BA/Leverhulme Trust (GrantBA/Leverhulme Trust Grant SRG18R1\180515). A more detailed version can be found here.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: Photo by Michael Pittman, Creative Commons — Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic — CC BY-SA 2.0