Leaving the EU would free up more money for the NHS, according to Leave campaigners. This pledge has been all but disowned – and in any case, writes Joan Costa-Font, Brexit will impose further costs on an already cash-strapped service. The biggest effect will be on wage bills, but it will also restrict choice for Britons and raise procurement costs.

Leaving the EU would free up more money for the NHS, according to Leave campaigners. This pledge has been all but disowned – and in any case, writes Joan Costa-Font, Brexit will impose further costs on an already cash-strapped service. The biggest effect will be on wage bills, but it will also restrict choice for Britons and raise procurement costs.

Healthcare and the National Health Service (NHS) budget were a key element of the Brexit referendum narrative: Vote Leave infamously promised that savings from paying into the EU budget could be spent on health, a pledge from which campaigners have since disassociated themselves. Indeed, the NHS is unlikely to benefit from Brexit – very much the contrary. Indeed, Brexit weakens the financial sustainability of the NHS.

According to estimates from the King’s Fund, in 2015–16 the NHS had the largest deficit in its history. NHS funding has been unable to keep pace with a growing demand for services. These financial constrains come at a time of staff shortages in most British hospitals, which have had to rely, as is common practice, on private temporary contract agencies and, more generally, on private providers who already make up 18% of the NHS spend on community health services.

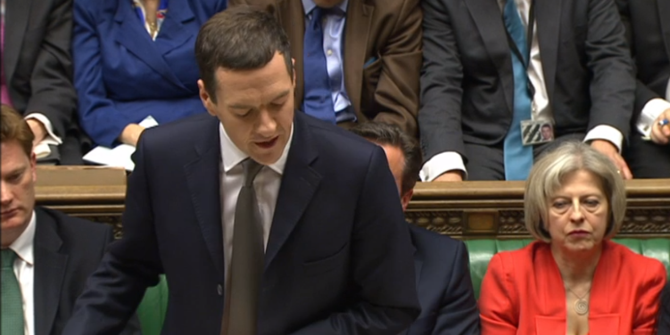

Photo: Tudor Barker via a CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0 licence

Photo: Tudor Barker via a CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0 licence

Leaving the European Union in such a context creates a conundrum for English hospitals. How can they square their need for cost savings with maintaining quality? Better-quality services inevitably mean extra resources, which are not available without extra funding. So Brexit raises questions about the financial sustainability of an unreformed NHS – that is, an NHS without additional money. Leaving the EU will lead to significant restrictions on labour mobility, which can shift labour costs upwards – for example, higher wages will be required to incentivise a declining medical workforce, and more vacancies might need to be covered by temporary staff. In addition, we can expect higher transaction costs for intermediary goods. Brexit is estimated to lead to a reduction of 6.3–9.5 % of national income which will mean even less revenues to fund the NHS.

Effect on the workforce

Even before Brexit, the NHS has struggled to recruit and retain permanent staff. In 2014, there was a shortfall of 5.9%, and in social care 5.4%, rising to 7.7% in care services in the home, and about one-third of all UK nurses are due to retire in the next ten years. The problem is even more alarming when one looks at the GP workforce. A recent report of the Royal College of Physicians suggests that, in 2016, 86% of physicians experienced shortages across clinical teams.

Reducing EU immigration would increase wages on both ends of the wage distribution. In such a scenario, the options available include incentivising EU immigration or expanding health and social care spending in an attempt to transform it into a higher-wage sector, with the aim to increase its productivity. Therefore, the trade-off is between saving NHS funds by hiring health professionals from overseas, or expanding health investment further to incentivise local recruits (with some delay as they are trained).

Brexit may offer an opportunity to get rid of the contentious European Working Time Directive (WTD) which limits the maximum amount of time that employees in any sector can work to 48 hours each week. In turn, raising working time limits is likely to cause a deterioration in the quality of NHS employment and make working for the NHS less attractive.

Effects on patients

The balance of payments associated with free patient mobility seems to have traditionally benefited the UK, given that British expats (who stop using the NHS) tend, overall, to be older than EU residents in the UK – who are on average younger, healthier and more highly skilled. After Brexit, UK citizens are unlikely to have the right to travel to the EU for treatment and therefore will enjoy less control over their healthcare. Furthermore, British tourists might be excluded from the European Health Insurance Card (EHIC) programme. The only advantage, from a welfare perspective, of restricting mobility is that discouraging it reduces competition between health systems. Hence it could be argued that mobility deters a ‘race to the bottom’ in healthcare investment.

Brexit almost certainly means higher costs for the NHS, especially labour, as I argue in more detail in a recent article in the Journal of Social Policy. As a consequence of Brexit, it will become more difficult to attract qualified staff and other inputs affected by non-tariff barriers (e.g. rules of origin checks, regulatory barriers, border controls etc.), and procurement will become more expensive. Certainly, Brexit does bring some opportunities too – including the possibility of redefining the NHS in new directions. Nonetheless, it takes place in the midst of a process of fiscal consolidation (leading to longer waiting lists, waiting times etc) and will create additional and unnecessary financial pressures.

______

This post was first published on the LSE Brexit blog.

Joan Costa-Font is an Associate Professor at the LSE in the Department of Health Policy and the European Institute, and an associate faculty of LSE Health and Social Care and the International Inequalities Institute.

Joan Costa-Font is an Associate Professor at the LSE in the Department of Health Policy and the European Institute, and an associate faculty of LSE Health and Social Care and the International Inequalities Institute.

Citizens from outside the EU, here on visas over 6 months (visa fees increased by 25% in 2016) have to pay an NHS surcharge in addition to the visa fees. The NHS surcharge has been set at £200 per year. Since it’s implementation in 2015, over £600 million has been raised. In December 2018, this surcharge was increased to £400 per year, hence doubling the amount to the NHS. Fantastic money earner for the Government, but has any of it been passed to the NHS? I would assume not as this should plug the huge hole in the NHS expenditure more than adequately. No mention of this is ever publicised. I would guess that Ms May intends to extend this surcharge to all non-British citizens if we leave the EU? What a money spinning plan she’s made! Personally, exasperated by this surcharge, as my husband commenced employment, paying tax and NI, 14 days after arriving in this country on his spouse visa, yet still has to pay the surcharge.

In addition to this conundrum, skilled non EU citizens, here on working visas, who are mainly in NHS positions, are not only capped to the number of visas authorised, the minimum income has been set to £35,000 should the individual wish to remain in the UK after 5 years! All of this is detrimental to the NHS, in terms of recruiting and salaries.

Why is it assumed that a post-Brexit NHS will be unable to recruit from abroad, as it did before the EU insisted on preferential treatment for EU citizens over those from other countries? Yes, there is a need to reduce overall immigration (unless, of course, any potential government plans to match net immigration with additional housing, education and access to services, which none of them has even mentioned to date). However, prior to the mutual recognition of member countries’ qualifications for medical staff, the NHS was free to recruit from the Philippines, India, the West Indies and other countries. It’s not foreign recruitment to meet need that has been the problem, but access as of right for EU citizens to all jobs open to UK residents.

You think EU citizens will continue to apply to jobs when they don’t have the same rights and the pound is on par with the euro? If the common employment market is broken by leaving the EEA, then the UK relies on Philipines and West Indies more than ever which comes at higher recruitment costs, or will have to increase wages, which will be an across the board rise in costs to the system,…or continue being understaffed and hence, implicitly promote private medicine,…