Debate surrounding drugs policy has often been emotive and lacking a solid evidence-base. Over 2,000 people a year in the UK are imprisoned for cannabis offences, despite the lack of any clear empirical evidence of an effect of enforcement activity on cannabis use. Drawing from a recent report he co-authored, Steve Pudney considers the costs and benefits of a system of licensed, regulated and taxed cannabis supply. He sees nothing in the findings to frighten any government or make legalisation unthinkable.

Debate surrounding drugs policy has often been emotive and lacking a solid evidence-base. Over 2,000 people a year in the UK are imprisoned for cannabis offences, despite the lack of any clear empirical evidence of an effect of enforcement activity on cannabis use. Drawing from a recent report he co-authored, Steve Pudney considers the costs and benefits of a system of licensed, regulated and taxed cannabis supply. He sees nothing in the findings to frighten any government or make legalisation unthinkable.

It is easy to despair of the low quality of public debate on drugs policy in the UK. Some of the loudest voices in the debate reflect fixed views and make opportunistic use of any fragment of evidence that happens to support those views. The very act of contemplating certain policy options can attract vehement criticism and – consequently perhaps – some policy-makers who, before entering government, had open minds on options for drugs policy, cling firmly to the prohibitionist line when in power. Few participants in the public debate on drugs policy are prepared to consider the full range of issues involved in policy choice, or acknowledge the large uncertainties that exist in the research evidence. The debate is often conducted in emotive terms, using vague conceptions of ‘tough’ and ‘liberal’ policy, sometimes making large deductive leaps that have little backing in logic.

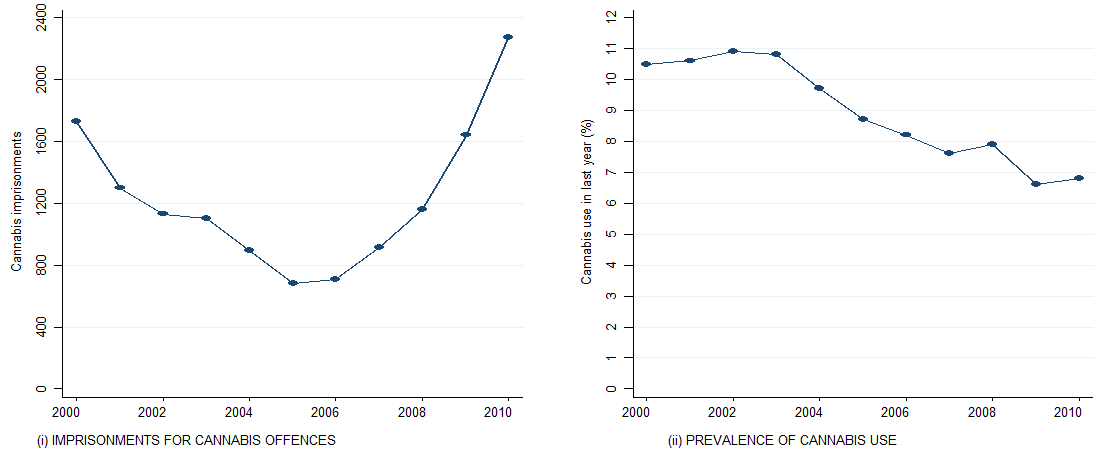

Cannabis is the most widely used illicit drug in Britain (the research reported here all relates to England and Wales rather than Great Britain or the UK). Although its use has been in slow decline for over a decade, analysis of survey evidence still suggests that there may be as many as 3.4m users (down from 5.5m in 2006), which exceeds the prevalence of all other illegal drugs combined. UK policy is prohibitionist: the users and suppliers of cannabis are threatened with maximum sentences of 5 and 14 years’ imprisonment respectively, and we currently imprison over 2,000 people a year for cannabis offences, despite the lack of any clear empirical evidence of an effect of enforcement activity on cannabis use (see Figure 1). This prohibitionist policy is dictated by international treaty provisions and aspirations which found expression in a remarkably implausible UN slogan “a drug-free world – we can do it!”

Figure 1: Trends in custodial sentences for cannabis offences and cannabis use

A recent report co-authored with Mark Bryan and Emilia Del Bono sets out the basis for a comprehensive and reasoned consideration of one radical policy option – a system of licensed, regulated and taxed cannabis supply. We identify no fewer than seventeen possible consequences that need to be evaluated before arriving at an informed and balanced view on the case for this reform. They include: savings in various policing and criminal justice costs; changes in cannabis-related crime, accidents, dependency, mental and physical illness, productivity, and the scarring effects of a criminal record. The tools of cost-benefit analysis can be used to put all projected consequences of reform – both monetary and non-monetary – on a common cash-equivalent basis, giving a coherent overall view of the arguments and some idea of which particular consequences might be crucial in tilting the argument one way or the other. We evaluate only the effect of the reform on the social costs imposed by cannabis users on the rest of society, and are able to make estimates of the net social benefits or costs of reform for 13 of the 17 items on our list of possible consequences.

There are large uncertainties in evaluating the costs and benefits of reform. The first is what a legalised market would look like. US models of legalisation lead to large numbers of suppliers and product heterogeneity that is hard to regulate. Other models, like the extreme case of a government monopoly proposed for Uruguay, entail fewer, larger licensed suppliers operating under tight product controls. The possibility of product regulation is one of the strongest arguments for legalisation. The primary psychoactive component of cannabis is D9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which has been linked to impaired brain function and psychotic symptoms, but research suggests that another component, cannabidiol (CBD) has a protective anti-psychotic effect. In the last decade or so, there has been a worrying rise in the market share of high-THC, low-CBD forms of cannabis (“skunk”, etc), and this worrying trend has proved impossible to control under prohibitionist policy.

A second major source of uncertainty is the nature of demand. It has not proved possible to arrive at a clear understanding of the reasons for the slow decline in cannabis use or the shift towards higher-potency product, nor is there any research consensus on price effects, especially the cross-effects of variation in cannabis prices on the demand for alcohol, tobacco and other drugs. A third difficulty is in identifying the true causal relationship between cannabis use and eventual long-term harms. Given these uncertainties, we consider three scenarios based on alternative assumptions about the responsiveness of cannabis demand to legalisation, and also give a subjective margin of uncertainty for each estimate.

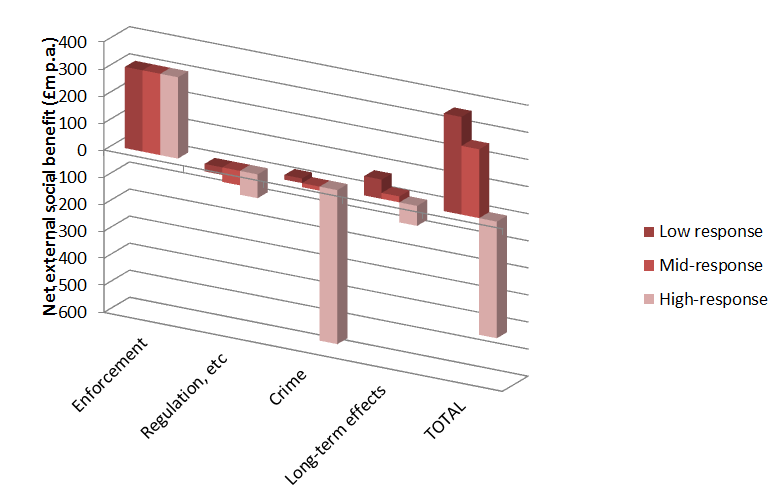

Figure 2 summarises the results. We assume a significant degree of product regulation, with government setting excise taxes at a rate comparable with those used in the alcohol and tobacco markets, and the continued existence of residual illegal supply with a market share rather larger than the share of illegal supply in the tobacco market at present. The striking feature of these estimates is how small the projected costs and benefits are. This is partly because we are only considering external costs and benefits, arguing that the anticipated private costs (e.g. health risk) to cannabis users themselves are necessarily outweighed by the anticipated enjoyment of consumption. But it is also partly because the plausible scale of cost savings (reduced enforcement costs, etc) and cost increases (medical care, crime victimisation, etc) to society appear to be inherently modest. There is no compelling evidence for a huge impact – either good or bad – on the rest of society from the changes in cannabis use likely to be produced by legalisation.

A possible exception to this is cannabis-related crime. Although we find very little evidence that cannabis use causes any crime at all, the large size of the market means that costs could be high under the most pessimistic “high response” scenario. But the large projected net increase in cannabis-related crime in that case (almost £600m) is highly uncertain, with a margin of error of plus or minus £800m.

Figure 2: Projected net social benefit of reform under three demand response scenarios

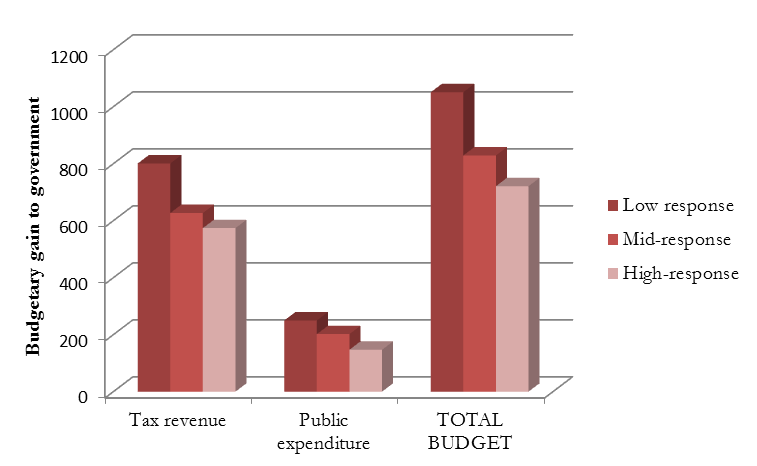

By far the largest projected impact relates to the government budget (Figure 3). Under this reform, government gains additional tax revenue from licensed supply and makes net savings on policing and criminal justice costs. Since taxes represent transfers within society rather than gains to society, the improvement in the government’s budgetary position is not a strong argument for reform in principle, but it might be an attractive feature of reform to governments in practice.

Figure 3: Projected gains to the government budget

We see nothing in these findings to frighten any government – there is no “killer fact” that makes legalisation unthinkable. While there is a significant possibility of net social harm if the demand response to policy change turned out to be extremely high, close monitoring of prevalence would allow the policy to be evaluated in practice and reversed if necessary.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Steve Pudney is Professor of Economics at the Institute for Social and Economic Research, University of Essex.

He is grateful to the Open Society Institute (OSI-ZUG) and UK Economic and Social Research Council through the Research Centre on Micro-Social Change (award no. RES-518-285-001) for supporting this research.