The resignations and leadership challenges in the wake of the Brexit vote have reignited debates around intra-party democracy. Tom Quinn offers an overview of the selection processes in the four main UK-wide parties and outlines both the challenge and importance of balancing MP and membership approval.

The resignations and leadership challenges in the wake of the Brexit vote have reignited debates around intra-party democracy. Tom Quinn offers an overview of the selection processes in the four main UK-wide parties and outlines both the challenge and importance of balancing MP and membership approval.

The aftermath of the EU referendum has brought a changing of the guard at the top of the UK’s political parties. The Conservatives already have a new leader, UKIP will soon have one and Labour may have one unless Jeremy Corbyn can win again just a year after being elected. These changes raise questions about the ways in which the parties choose their leaders, and the case of Labour in particular has brought to the fore an old debate about the merits of internal party democracy.

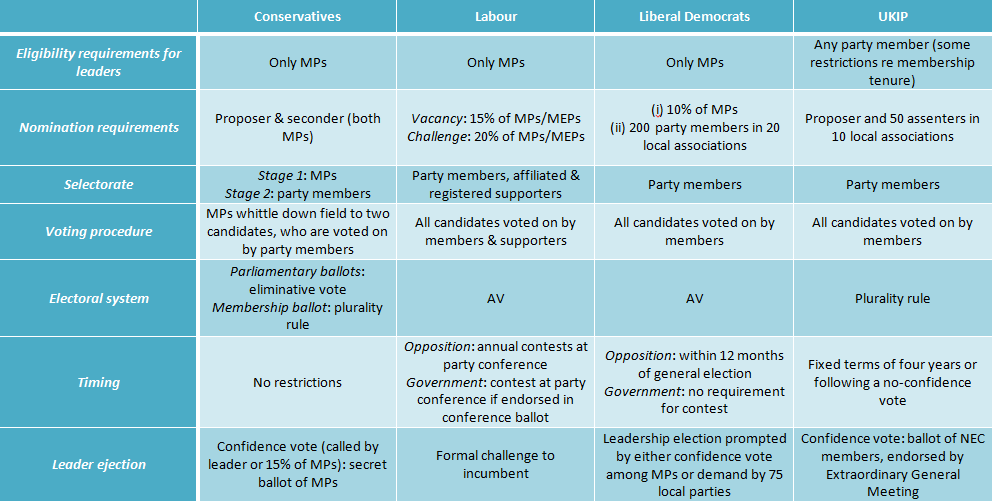

All four major UK-wide parties use a form of one-member-one-vote (OMOV) in leadership selection and allow their members to make the final choice (see table for details). However, there are differences in the role they allocate to MPs.

In the Conservative Party, leadership candidates must be nominated by two other MPs. If only two candidates are nominated, they immediately go forward to a postal ballot of individual party members. If there are more than two candidates, they must navigate a series of ballots of Tory MPs, with the least-supported candidate being eliminated until two are left. They go forward to a membership ballot. It does not matter if a candidate secures an overall majority of MPs’ votes, as Theresa May recently did. The final choice lies with the mass membership. Meanwhile, a confidence vote can be called in a leader if 15 per cent of Tory MPs demand one in writing. If granted, the leader needs a simple majority in a secret ballot of MPs to survive. Individual members do not participate.

Labour leadership candidates must be nominated by 15 per cent of Labour MPs when there is a contest for a vacancy or by 20 per cent when it is a challenge to an incumbent leader. Candidates passing the relevant threshold then go forward to a postal ballot of full party members, as well as two other categories of participants. Affiliated supporters are trade unionists who have signed up for free to vote in the contest, and registered supporters are members of the public who have paid a small fee (£3 in 2015 but £25 in 2016) to vote. All selectors’ votes are counted together with no separate sections for each classification of selector. There are no formal provisions for confidence votes.

The Liberal Democrats require candidates to be nominated by 10 per cent of Lib-Dem MPs and by 200 individual party members covering 20 constituencies. All nominees go forward to a postal ballot of members. UKIP requires leadership candidates to be nominated by a proposer and 50 assentors drawn from 10 constituencies, but not by any MPs. Again, nominees advance to a postal ballot of party members. UKIP specifies fixed four-year terms for its leaders, with leadership elections required at the end of these terms, although incumbents may stand again.

Leadership Selection Procedures in the Four Main UK Parties

The arguments for and against intra-party democracy are well-known. The ordinary members who pay subscriptions to and campaign for the party should, in exchange, have a say over its policies, its candidates, and its leader. Without this influence, they have little incentive to stay in the party, yet their efforts are vital for it to remain operational and a campaigning force. From this perspective, it is right that members choose their leaders and the latter should implement policies that reflect the members’ preferences.

Against this position is the fact that party members are typically an unrepresentative section of voters, as is evident in the Labour Party today. If they impose ‘extreme’ policies or choose unelectable leaders, the party will lose elections. For this reason, the ascendancy of a party’s MPs is offered as an alternative to grassroots control. MPs are collectively elected by millions of voters and are usually more reflective of voters’ preferences.

The Conservatives and Labour have sought to square this circle by devising selection systems that give influence to both groups. That is evident in the Conservatives’ two-stage system and in Labour’s requirement that candidates must be nominated by 15 per cent or MPs – though in the case of Corbyn in 2015, this provision was deactivated by those MPs who nominated him ‘to broaden the debate’ rather than because they genuinely supported him.

There are practical reasons why a leader needs to have the support – or at least, the consent – of his/her MPs. In a parliamentary democracy, the government is drawn from the legislature, with MPs (and some peers) filling its ranks. The PM holds ultimate power in the British system and appoints MPs to ministerial positions. However, leaders who lose the confidence of their MPs find it difficult to carry on. A mass-resignation of front-benchers in government, of the type witnessed in the Labour Party in opposition recently, would leave the executive unable to govern, irrespective of how much support the PM had among the membership. The PM’s position would be untenable.

In opposition, if a party is to present itself to voters as a government-in-waiting, the same parliamentary discipline is essential. Without it, a party looks divided and rudderless. Even Corbyn’s supporters tacitly acknowledge this point when they raise the spectre of mandatory reselection of MPs. Its purpose would be to replace some MPs and pressurise others to obey the leader, ensuring a more united parliamentary party, albeit on Corbyn’s terms.

Recent concerns about intra-party democracy have indeed largely been driven by the experience of Labour. But probably the major issue here was the rapid influx of new members after the 2015 general election. Such surges over such a short period would have been unfeasible in the past but have become easier in an era of social media, where hundreds of thousands of people can be mobilised into a party with the aim of capturing it and voting in its internal elections. That was made possible by the lack of a qualification period before new members could vote in the 2015 Labour leadership contest.

Labour has backtracked on this in 2016. Without such restrictions, there is a risk that parties lose their organisational integrity, as they become too open and vulnerable to intensely-motivated but unrepresentative minorities. If that happens, parties become protest movements and cease to perform the crucial functions of democratic linkage between voters’ preferences and governmental policy outcomes. They risk becoming electorally uncompetitive and by failing to offer an alternative government, they enable the existing one to get away with controversial decisions.

When MPs oppose the leader that members impose on them, parties risk becoming dysfunctional. It perhaps explains the relief among many Conservatives when Andrea Leadsom withdrew to allow May, the choice of 60 per cent of MPs, to become leader without a membership ballot. If the members had chosen Leadsom, the Tories could have faced a similar problem to Labour’s, except while in government. Internal democracy was sacrificed for practicality. It remains to be seen how Labour’s opposite choice turns out.

____

Note: this post was originally posted on Democratic Audit.

About the Author

Tom Quinn is Senior Lecturer in the Department of Government at the University of Essex.

Tom Quinn is Senior Lecturer in the Department of Government at the University of Essex.

There are four main UK parties?

None of the four mentioned stand for election across the UK. I rather suspect that the author actually means that there are four main parties in England, which is the populous component of the UK.

If this had been an undergraduate essay, I would have failed it for lack of accuracy.

I note that the third biggest party in the House of Commons doesn’t even get a mention.