Does the fear of being bullied in childhood affect people’s resilience to adverse life events they may face in adulthood? Nattavudh Powdthavee investigates whether the ‘scarring’ effects are particularly damaging to individuals who lose their job.

Does the fear of being bullied in childhood affect people’s resilience to adverse life events they may face in adulthood? Nattavudh Powdthavee investigates whether the ‘scarring’ effects are particularly damaging to individuals who lose their job.

Research on the economics of happiness has shown that, on average, people of working age who are unemployed report significantly lower mental health and life satisfaction than those who have a job. They also find it hard to adapt completely to being unemployed. But is the impact of job loss even worse for people who had reported fear of bullying when they were children? In a recent study, I explore whether adults who were afraid of being bullied at school find it even harder than others to withstand and adapt to unemployment shocks, perhaps due to the early loss of self-esteem.

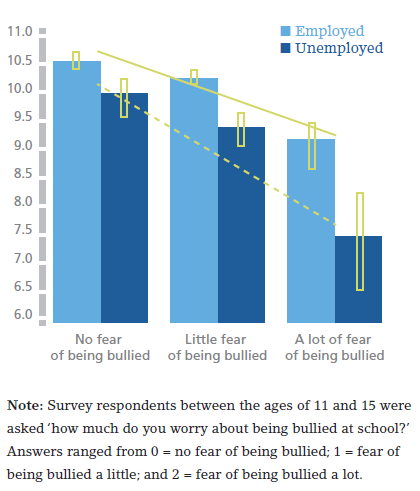

Using a nationally representative longitudinal data set for the UK, which tracks almost 3,000 children (11-15 years old) into adulthood (16-29 years old), I find that on average, the unemployed report worse mental health and lower life satisfaction scores than the employed, holding constant how much they feared being bullied in the past. Similarly, holding employment status constant, people who feared being bullied more in the past report lower mental health and life satisfaction scores as adults.

Using a nationally representative longitudinal data set for the UK, which tracks almost 3,000 children (11-15 years old) into adulthood (16-29 years old), I find that on average, the unemployed report worse mental health and lower life satisfaction scores than the employed, holding constant how much they feared being bullied in the past. Similarly, holding employment status constant, people who feared being bullied more in the past report lower mental health and life satisfaction scores as adults.

These findings indicate that unemployment hurts, but it hurts more for individuals who had a persistent negative experience as a child. Figure 1 shows how the wellbeing gap between the employed and the unemployed is larger for those who reported having experienced higher levels of fear of school bullying in the past. The estimated effect is quantitatively important as well as statistically significant.

Figure 1: Mental health of the employed and the unemployed by categories of childhood bullying

Take, for example, the gap in mental health between the unemployed who reported no fear of being bullied as a child and the unemployed who reported high levels of fear. The difference in the mental health score for these unemployed individuals is equivalent to the effect of becoming disabled, the effect of a move from having ‘excellent’ health to having ‘very poor’ health or the effect of having up to eight children in the household.

What about differences in people’s ‘hedonic adaptation’, their ability to bounce back to a relatively stable level of happiness despite a major life change? When we compare the dynamics of wellbeing between people with different bullying backgrounds, we find that there is virtually no hedonic adaptation to unemployment among those who had feared being bullied a lot during childhood.

By contrast, people who had reported no fear of bullying at school between the ages of 11 and 15 report a significant drop in mental health only in the first year of becoming unemployed. In other words, it is not only the case that people who feared being bullied a lot in the past are less resilient to unemployment shocks, but they are also less likely to adapt to the unhappiness brought about by unemployment.

There are at least two important implications of our findings. The first is purely descriptive: these results are consistent with the general predictions of traditional lifecourse analysis. These indicate that people’s psychological resilience and ability to adapt quickly and completely to negative life shocks can be determined early on in their childhood.

In the last few decades, social scientists have been gathering enough longitudinal evidence to establish that humans do reclaim some – if not all – happiness from despair and that we are surprisingly good at surviving the blackest of blacks. For example, it has been demonstrated in nationally representative data sets that it only takes a few years for people to adapt completely to the unhappiness caused by bereavements and marital splits. But until now, we have known little about why some people are better (or worse) than others at bouncing back from significantly bad life events and why they are initially hurt less (or more) by such shocks.

The second implication is normative: whenever possible, policy-makers would like to be able to identify those individuals who are destined to suffer the most from shocks to their economic circumstances. Thus, knowing which childhood indicators can be used to identify children who are at risk of growing up without the skills to cope with adverse life events naturally becomes one of the keys to optimal policy design.

One such childhood indicator seems to be the fear of bullying that an individual has experienced. This confirms the value of surveys such as that undertaken by the Department for Children, Schools and Families in 2010, which indicated that almost half (46%) of children said they had been bullied at school at some point in their lives.

This article summarises ‘Resilience to Economic Shocks and the Long Reach of Childhood Bullying’ by Nattavudh Powdthavee, CEP Discussion Paper No. 1173.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Nattavudh Powdthavee is a principal research fellow in CEP’s wellbeing programme.