The DUP’s illiberal views are at the centre of attention. But what about the strategies that underpin political agendas in Northern Ireland? Bernadette C. Hayes and John Nagle examine the attitudes of DUP and Sinn Fein supporters towards same-sex marriage and abortion. They find that the two groups tend to diverge over issues that are subject to ethnonational contestation (LGBT rights) and are unified over those that are not (abortion).

The DUP’s illiberal views are at the centre of attention. But what about the strategies that underpin political agendas in Northern Ireland? Bernadette C. Hayes and John Nagle examine the attitudes of DUP and Sinn Fein supporters towards same-sex marriage and abortion. They find that the two groups tend to diverge over issues that are subject to ethnonational contestation (LGBT rights) and are unified over those that are not (abortion).

The likelihood of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) entering into a confidence and supply arrangement to bolster Prime Minister Theresa May’s beleaguered government has drawn disquiet, not least within the higher echelons of the Conservative Party. While one former Conservative Prime Minister voiced deep anxiety at the potential negative impact of the pact on the Northern Ireland peace process, rising star Ruth Davidson, the leader of the Conservative party in Scotland, questioned the morality of a deal with a party implacably opposed to LGBT rights. Another senior Conservative MP, Owen Paterson, warned of the possibility of the DUP pushing for a parliamentary debate on reducing abortion time limits in Britain.

However, more so than any other moral issue, the contention that the DUP – as one journalist puts it – is characterised by a ‘pathological obsession with homosexuality’, is, by far, the most persuasive argument and not without strong evidence. From the formation of the party in the 1970s, leading members publicly articulated homophobic sentiment and the party wields its power to resist key gay rights policy changes.

What drives the DUP’s anti-gay rights agenda? A credible answer concerns the DUP’s roots as an evangelical Protestant party which frames homosexuality as a sin and an abomination against Biblical scripture. Yet, the DUP’s Christian Fundamentalism tells only half the story. A more complete answer needs to take into account the political pragmatism of the DUP as supporters of the unionist population in relation to the Northern Ireland peace process in which human rights have become a ‘war by other means’.

Save Ulster from Sodomy

Formed in 1971 during the emergence of the Northern Ireland conflict, the DUP’s primary ambition was to smash the IRA thus ensuring Northern Ireland’s continued position within the Union. Led by the Rev. Ian Paisley, a Protestant Fundamentalist firebrand, the DUP was institutionally intertwined with his church, the evangelical Free Presbyterians. The DUP’s brand of religious conservative nationalism shaped its worldview on sexuality.

Most infamously, in 1978, Rev. Ian Paisley, then an MP, collected nearly 70,000 signatures as he led a petition to stop the ending of criminalisation of homosexuality in Northern Ireland – a campaign titled ‘Save Ulster from Sodomy’. Since then, a number of DUP political representatives expressed homophobic sentiments, including branding sexual minorities as ‘abominable and filthy’ and to blame for AIDS in Africa and Hurricane Katrina, and labelling homosexuality ‘disgusting, loathsome, nauseating, shamefully wicked’ and ‘an abomination’.

It appears little surprise that these beliefs found expression in its political policies, particularly as the leading party in the Northern Ireland power-sharing Assembly. Edwin Poots, a DUP politician and Minister for Health, used his position to maintain a ban on gay people donating blood – a policy the courts decided was driven by Poots’ religious convictions.

However, it is the DUP’s blocking tactics on same-sex marriage that generates the most comment. As the largest party in the power-sharing government, the DUP passed the 30 seats threshold required to exercise sole veto power. Since 2013, the DUP deployed a petition of concern – effectively a communal veto – on five occasions to stop the extension of same-sex marriage legislation to Northern Ireland.

To be sure, the DUP’s resistance to same-sex marriage legislation stems partly from the evangelical beliefs of its membership. Yet we need to understand this opposition as fundamentally rooted in the DUP’s tactical political manoeuvring within the framework of power-sharing.

LGBT rights as war by other means

Looking at the workings of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement (GFA) and its power-sharing executive provides some insight to the DUP’s position on LGBT rights. The GFA created a framework that endowed ‘parity of esteem’ for the rights and identities of Irish nationalists and unionists as part of power-sharing. For Irish nationalists, parity of esteem represented the institutional expression of the ‘equality agenda’, a positive process of redressing the historical experience of inequality and exclusion of the nationalist population.

For unionists, the Agreement was felt as a loss. The equality agenda – such as the reform of policing and restrictions on Orange Order parades – were perceived as a nationalist-led creeping barrage to hollow out unionism. Such a perspective is not without some grounds: Sinn Fein President Gerry Adams stated that the equality agenda is the ‘Trojan horse of the entire republican strategy’. By 2003, unionist support for the Agreement slowly eroded, a dynamic successfully seized on by the DUP to electorally outperform their unionist rivals – the UUP – who they frame as weak defenders of unionism.

Given that issues of equality and human rights generate conflict between unionists and nationalists, LGBT rights have become embroiled in this struggle. Some evidence of this is seen in the contrasting positions of the DUP and its nationalist rivals Sinn Fein on same-sex marriage. Sinn Fein strongly support same-sex marriage and tabled five motions on same sex-marriage legislation for the power-sharing parliament to vote on. LGBT rights, more broadly, are seen by Sinn Fein as synonymous with minority rights, which include nationalists. As ‘Moving On’, Sinn Féin’s ‘Policy for Lesbian, Gay and Bi-Sexual Equality’, states: ‘… [nationalists] are only too well aware of what it means to be treated as second-class citizens. Our politics are the results of decades of resistance to marginalisation and discrimination’.

The DUP’s resistance to same-sex marriage – while shaped by religious conviction – is also a tactical decision to oppose what they view as nationalists’ co-option of minority rights as a tool to erode unionism. To an extent, LGBT rights present Sinn Féin with a weapon to poke the DUP. The DUP are framed as reactionary and homophobic in contrast to Sinn Féin’s liberal and progressive leanings.

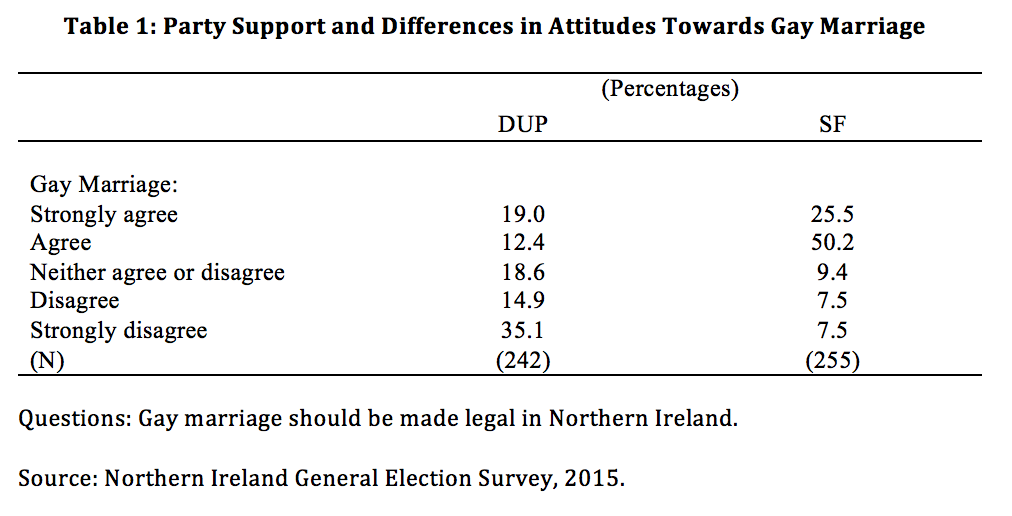

These divergent views on same-sex marriage are mirrored in public opinion. Survey evidence from the 2015 Northern Ireland General Election Survey demonstrates that DUP supporters are much less likely to endorse same-sex marriage legislation than those who support Sinn Fein. As the data in Table 1 shows, whereas only 31% of DUP supporters were in favour of the legalisation of gay marriage, the equivalent proportion among Sinn Fein supporters was 45% higher – at 76%.

By contrast, while exactly half of DUP supporters were opposed to such an initiative, the equivalent % for supporters of Sinn Fein was just 15%. This pattern is replicated when views within their respective constituents, or the Protestant and Catholic community, are considered. For example, whereas just around two-fifths, or 41%, of Protestants supported the legalisation of gay marriage, the equivalent percentage among the Catholic population was markedly higher, at 67%.

Evidence that LGBT rights are as much a political as a religious matter can be seen by looking at the question of abortion. Currently, Northern Ireland has the harshest criminal penalty for abortion in any country in Europe – up to life imprisonment for both the woman having the procedure and anyone assisting her. Statistics from the Northern Ireland Department of Health estimate that around 1,000 women a year travel from Northern Ireland to England and pay up to £2,000 to obtain an abortion privately, as they are not entitled to a NHS abortion in England. Yet, both Sinn Fein and the DUP refuse to support the full extension of the 1967 abortion act to Northern Ireland, though it should be noted that Sinn Fein support abortion on the grounds of unborn children having life-limiting conditions and on the act of sexual crime while the DUP reject any change.

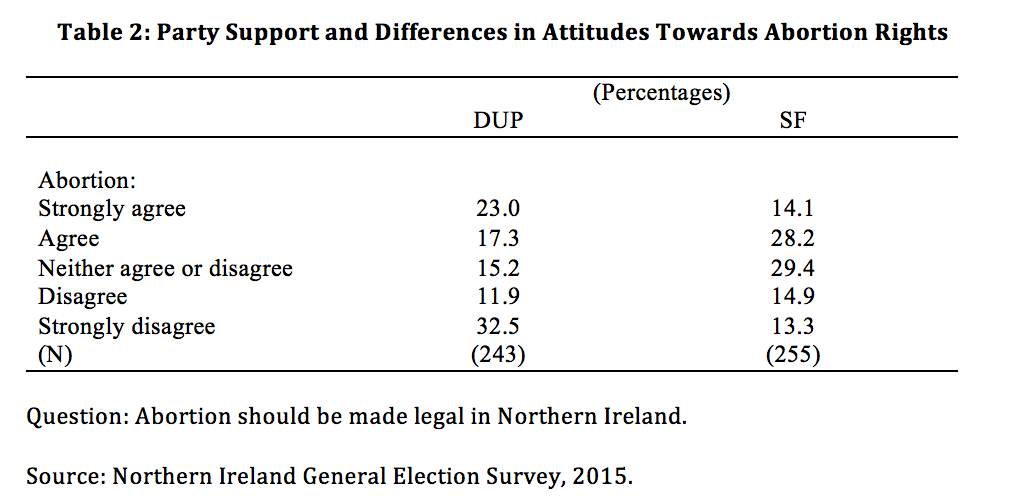

Survey data suggests, however, that not only are DUP supporters more likely to ‘strongly support’ the legalisation of abortion rights than their Sinn Fein counterparts – 23% versus 14% – but they are also notably divided in their views (see Table 2). For example, whereas exactly two-fifths (40%) of DUP supporters endorsed such an initiative, 44% were opposed to such a move. Moreover, there is evidence to suggest that at least as far as support for the legalisation of abortion is concerned, at 40% and 42% respectively, both DUP and SF supporters are now almost identical in their views. Again, a similar pattern emerges when opinions within their respective constituents, or the Protestant and Catholic community, are considered; whereas 47% of adults within the Protestant community were willing to endorse the legalisation of abortion, the equivalent figure among their Catholic counter-parts was 40%.

What may explain this finding, or the almost equivalent support for abortion rights among DUP and Sinn Fein supporters? As noted earlier, LGBT rights have been championed by Sinn Fein as synonymous with minority rights, including the rights of nationalists. This is not the case, however, when abortion rights, or the question of a woman’s right to choose, is considered which Sinn Fein has not endorsed as a minority rights issue. Thus, rather than inherent social conservatives, this finding of almost equivalent support for abortion rights suggests that unionists and DUP supporters may not be too different to their nationalist neighbours when issues are not subject to ethnonational contestation.

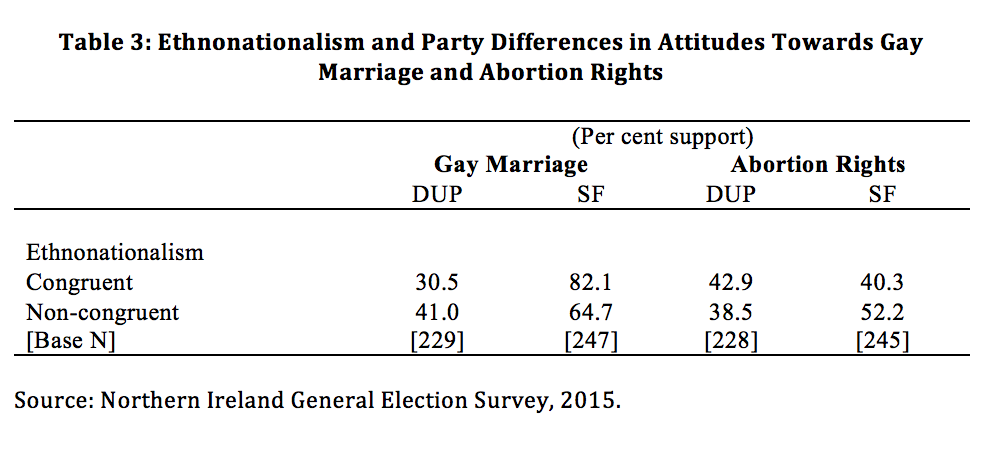

Survey evidence again lends some support to this interpretation. As the data in Table 3 demonstrates, while congruency in ethnonational identity – the extent to which Protestants see themselves as British and adopt a unionist label, and Catholics see themselves as Irish and choose a nationalist label – has a differential and positive impact on attitudes towards gay marriage among SF supporters, this is not the case when DUP supporters are considered. For example, whereas 82% of Sinn Fein supporters who saw themselves as Irish-nationalists were supportive of gay marriage as compared to just 65% who did not, the equivalent proportions among DUP supporters were 31% and 41% respectively.

A similar, albeit converse, pattern emerges when abortion rights are considered. Here, while DUP supporters were almost equally divided – 43% versus 39% – in relation to the issue, among Sinn Fein supporters it is individuals who rejected a dual-identity label that stand out as the most positive in their views.

There is no doubt that the DUP’s resistance to same-sex marriage legislation stems partly from the evangelical beliefs of its membership. Yet we need to understand this opposition as fundamentally rooted in the DUP’s tactical political manoeuvring within power-sharing. The party’s recent history of engaging with power-sharing highlights its capacity for pragmatism and relative moderation. For example, while the DUP initially took a hardline stance against the GFA and Sinn Fein’s presence in government, in 2007 it decided to enter into a power-sharing government alongside Sinn Fein. It is not altogether inconceivable that the DUP could move to a position that, while it may not support same-sex marriage, it may not necessarily vote to oppose it.

The prospects of this event materialising were somewhat enhanced by the outcome of the March 2017 Assembly elections which saw the DUP go under the 30-seat threshold needed to maintain veto power. In the event of the power-sharing government resuming, the DUP will effectively be powerless to halt same-sex marriage legislation. This may not be the case, however, in relation to the legalisation of abortion where, despite recent survey evidence – the 2016 Northern Ireland Life and Times Survey – that suggests overwhelming public support for a change in the law, both the DUP and Sinn Fein may continue to act as the moral guardians of a woman’s right to choose, and remain unified in their lack of support for such an initiative except in the case of rape and incest.

_____

About the Authors

Bernadette C. Hayes is Chair in Sociology and Director of the Institute of Conflict, Transition, and Peace Research (ICTPR) at the University of Aberdeen. She has published extensively in the areas of gender, politics, religion, and social stratification at both the national and international level. For a full list of publications see here.

Bernadette C. Hayes is Chair in Sociology and Director of the Institute of Conflict, Transition, and Peace Research (ICTPR) at the University of Aberdeen. She has published extensively in the areas of gender, politics, religion, and social stratification at both the national and international level. For a full list of publications see here.

John Nagle is Lecturer at the School of Social Science, University of Aberdeen. He has published three books (including Multiculturalism’s Double-Bind and Shared Society or Benign Apartheid?) and a number of articles in leading international journals. John’s latest book is entitled Social Movements in Violently Divided Societies: Constructing Conflict and Peacebuilding.

John Nagle is Lecturer at the School of Social Science, University of Aberdeen. He has published three books (including Multiculturalism’s Double-Bind and Shared Society or Benign Apartheid?) and a number of articles in leading international journals. John’s latest book is entitled Social Movements in Violently Divided Societies: Constructing Conflict and Peacebuilding.

Image credit: Pixabay/Public Domain

1 Comments