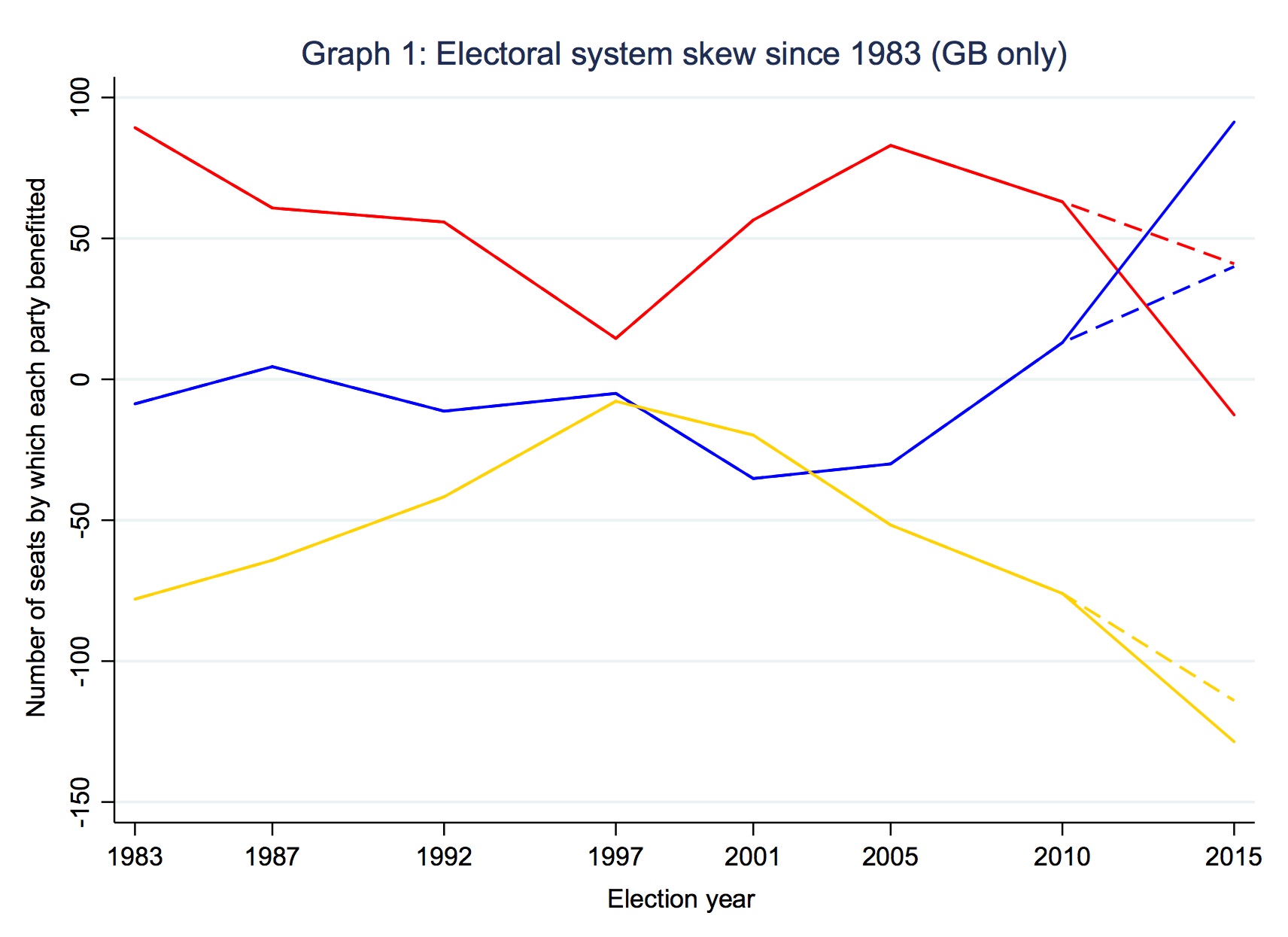

Historically, the electoral system has tended to help Labour in the way it translates votes into seats. In 2015, the skew changed, giving a significant advantage to the Conservatives, argues Tom Lubbock.

A week before the election I wrote an article on this blog setting out how the electoral system was set to benefit each of three parties based on the forecast results (we can can make such an estimate by running the result in each seat through algorithms that transpose each party’s result onto the other party’s distribution of votes).

The headline finding in the pre-election piece was that the electoral system was set to skew to Conservatives and Labour equally. Good news for the Conservatives, placing them in a more positive position than any in the last three decades of contests with Labour.

This forecast electoral skew is shown by dashed lines in Graph 1. The actual skew, derived from the 2015 result in each seat, is shown by the solid line. The extraordinary new conclusion from the actual results is that the electoral system in 2015 rewarded the Conservatives by more seats (net) than it did Labour during any of the well-skewed Blair elections. Don’t just take it from me, speaking on The World at One today Prof John Curtice said that Labour needs to be 12 percentage points ahead in England and Wales to win a majority of the seats in the Commons.

The benefit the Conservatives got from the electoral system at this election is not simply a function of the their victory or the scale of it. Look, for example, at the way the electoral system skewed in 1997 when Blair won his landslide. A modest 20 net seat advantage was delivered to Labour, whilst their Majority was 147. In fact this represented a skew that was decreased from 1992. What the skew tells us is the way that a party wins and loses– in which seats and by what majorities — not that it wins or loses.

Guess what is driving this skew? Yes that’s right, bad news for Labour in Scotland and good news for the Conservatives in England and Wales.

Scotland is at the heart of much of the GB wide skew. We can see that this is the case with a simple thought experiment. Imagine that Labour had won the Conservatives GB wide vote share of 38%. To simulate this increase Labour’s vote share in each seat by the 7 percentage point difference between the actual and hypothetical outcomes. Now count how many seats Labour would have retained (or if we want to think about the future, regained) at the SNP’s expense. None. A vote share swing of that magnitude does not help Labour in seat share terms (in Scotland) and hence each of those additional votes would be ‘wasted’.

The situation in Scotland is extreme, but the same story has played out in England and Wales. The Conservatives have a familiar advantage in the seats they now hold. They have a series of large majorities in the set of seats that Labour would need to win to be the largest party let alone form a majority government. These majorities are resistant to hypothetical, and by implication real, swings.

All this analysis of algorithms, vote share, seat share and swing can be simplified into two numbers from which a common sense conclusion reveals exactly the same picture. Labour needed 40,000 votes to win a seat at the general election whilst the Conservatives needed only 35,000 votes for each seat they won. Add in the Liberal Democrats at 300,000 votes and UKIP at 3.8 million votes per seat and you have a good argument for electoral reform. We’ll be talking about that again in 5 year’s time.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the General Election blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Dr Tom Lubbock is Lecturer in Politics at Regent’s Park College, University of Oxford

Dr Tom Lubbock is Lecturer in Politics at Regent’s Park College, University of Oxford

2 Comments