In response to Ken Loach’s new film Spirit of ’45, Adam Lent makes the case that the popular narrative of social change expressed in the film is mistaken. The social state established by the postwar Labour government of 1945 is not in decline but rather has continued to grow. He argues that we must now find a unifying ideal, with the same power as the ‘Spirit of 45’, in order to make the necessary transition from a state designed to ameliorate failure to one which generates success.

In response to Ken Loach’s new film Spirit of ’45, Adam Lent makes the case that the popular narrative of social change expressed in the film is mistaken. The social state established by the postwar Labour government of 1945 is not in decline but rather has continued to grow. He argues that we must now find a unifying ideal, with the same power as the ‘Spirit of 45’, in order to make the necessary transition from a state designed to ameliorate failure to one which generates success.

All credit to Ken Loach for directing our attention back to the epoch-shaping Labour Government of 1945. It speaks to a time when many fear that the last vestiges of what Attlee, Bevan and Dalton built are being torn down. The truth is, however, that the narrative behind the longing for the ‘Spirit of 1945’ is wrong. Political values may have shifted unrecognisably from that period but in terms of cold hard cash, Beveridge and Attlee remain the towering figures of our age. In fact, their importance has only grown.

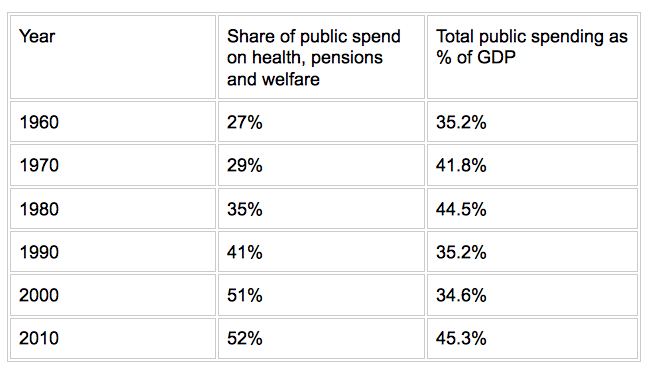

The three areas that the Attlee Government hard-wired into the fabric of state provision were pensions, healthcare and social security. A brief look at the change in the share of public spending going to these areas reveals why, far from fading, the ‘Spirit of 1945′ is in the sort of health that would make Nye Bevan proud:

The trend is incontrovertible and, as the right hand column shows, the growth is not the result of ‘Beveridge spending’ taking a bigger share of a shrinking state. There is also no sign that the growth will reverse given an ageing population, growing demand on the NHS and the higher unemployment rates we have experienced since the mid-1970s.

So the real challenge is not how we return to some lost world of pre-Thatcher glory but how we maintain a civilised and just society when the mechanism established under Attlee to do this has become unsustainable. As the FT columnist Janan Ganesh wrote last year:

Seventy years on, the benevolent thrust of the Beveridge report jars with the recent resurgence of the defining problem of economics: scarcity. But the intellectual boldness of the document is what the age requires. The UK needs an equivalent of the report from the opposing perspective – a strategic vision of the state that seeks to gradually contain its cost by narrowing its ambition.

The notion of the Big Society was, of course, supposed to do this rethinking. However, when one looks at the scale of growth in the table, the idea that a half-baked marketing concept might genuinely recast seventy years of the Beveridge behemoth was always ludicrous.

A ‘success state’ not a ‘failure state’

Ganesh is right, we need something as powerful as the Spirit of ‘45. That power came in some large part from the clarity and simplicity of the message: the idea that giving the state a much more active part in the life of the individual would slay the five giants of disease, squalor, ignorance, idleness and want that the free market could not defeat.

Since that point, the right has tilted constantly at the extra role this gives to government. Their alternative guiding principle has been the notion that the state is a malign interference in the beneficial operation of the market and its cornerstone of individual responsibility. However, despite eighteen years of Conservative Government inspired by this view (and three more since 2010), the figures above show how ineffective this has been as a mobilising ideal.

The problem is that the enlarged role for the state acted as a dog whistle for the right detracting their attention for decades from the other very significant aspect of the Spirit of ’45. This is its deeply remedial nature: the notion that the role of the state is to pick up the pieces resulting from the failure of the market and the individual. In short, the state steps in when things go wrong. The obvious alternative view that the state may have a role in stopping things going wrong in the first place has always been the less favoured sibling despite the fact that it is potentially just as powerful and fruitful as the remedial conceptualisation.

As a result, we have a state that spends more on welfare than on education (17% of total public spending versus 13% in 2012), commits only 2% of the healthcare budget to prevention and public health and spends £1.5 billion on a hotchpotch of benefits for better off pensioners rather than using the money to help older people stay in work, set up a business or volunteer.

The importance of shifting to a state designed to generate success rather than ameliorate failure is two-fold. Firstly, it is an optimistic notion of what can be achieved by state action which chimes far better with the more aspirational age we live in now. And secondly, it may prove an effective way of saving money over the medium to long term. Better educated citizens are less likely to be poor and unemployed, citizens who take care of themselves are less likely to get ill and older people who work longer or remain active are less likely to require state support.

So ultimately, the goal of those who would like to see the state back on a sustainable fiscal path while also holding true to a vision of a civilised and just society is to find ways to replace our ‘failure state’ with a ‘success state’. In short, this would be a state that is less about protecting people against the flaws of a free society and economy and more about helping them to enjoy all that a free society and economy has to offer.

This was originally posted on the RSA blog.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Adam Lent is Director of Programme at the RSA. He tweets from @AdamJLent.