Using data from the Understanding Society survey, Kirby Swales explains that the relationship between income and financial well-being is more complex than often assumed, and so a broader view of living standards could give greater insights into how best to help people react to changes in the economy.

Using data from the Understanding Society survey, Kirby Swales explains that the relationship between income and financial well-being is more complex than often assumed, and so a broader view of living standards could give greater insights into how best to help people react to changes in the economy.

It is well known that Britain has faced the longest period of stagnating incomes for many decades. Indeed it is only recently that real average household incomes recovered to pre-2008 levels, and real earnings growth has still not picked up momentum. This is clearly one of the most important social trends of our time, and is rightly the focus of intense research and policy interest.

Income is not, however, the only lens to look at our living standards. Tracking how much income households have needs to be complemented by other measures of financial and economic status. For example, others have argued that levels of spending are a valid measure of living standards, especially for those on low incomes. Our new analysis of self-reported financial well-being reveals a more complex relationship between income and financial well-being than may usually be assumed.

NatCen have previously written about levels of self-reported financial well-being, and we have now updated our tracking of one of the key measures of this: how well people feel they are managing financially. This is asked in the Understanding Society study – a large-scale survey of UK households, and is now included in ONS ‘well-being’ dashboard too.

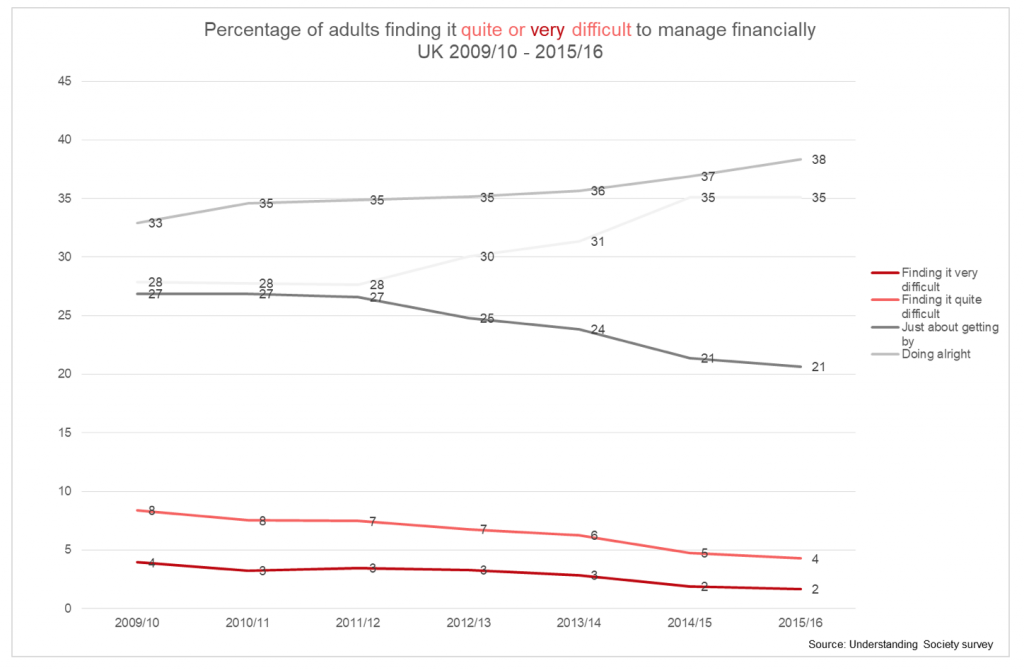

Our previous analysis showed that levels of financial insecurity rose dramatically at the start of the recent recession (when about 12 % of adults were saying that they found it ‘difficult’ or ‘very difficult’ to manage financially). We now see that there has been a continuing steady improvement, with fewer people feeling financially insecure. This is somewhat at odds with what we may expect given the reduction in real terms income over the same period. This could be driven by a number of factors, such as: people managing their finances more tightly; using savings and other assets; and a generally lowering of expectations around living standards.

This may go some way to explain why the long and difficult squeeze in incomes has not had greater political consequences. Households have been able to change the way they manage their household finances. Of course, however, this is an unequal picture, with certain groups (those unemployed, living with a disability, lone parents) more likely to say they are experiencing financial difficulties. About one in ten adults have been in financial difficulty for at least three of seven years of data we examined.

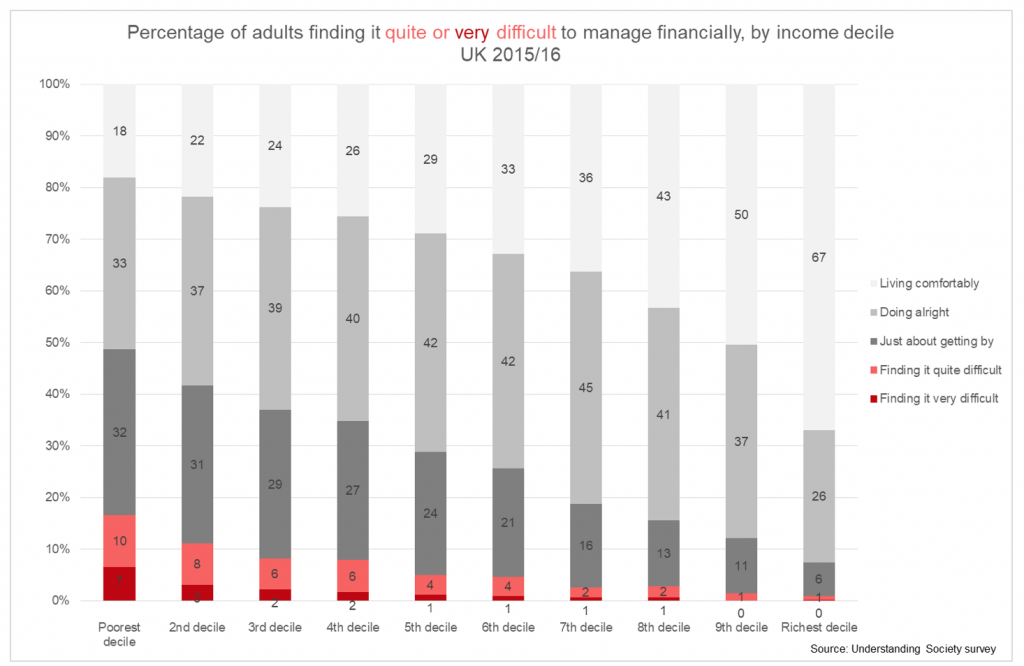

There is a clear relationship with income, as feelings of financial hardship increase with lower incomes. However, about a fifth of those in the poorest decile feel they are living comfortably or doing alright, whilst a quarter of those who are middle income (5th decile) feel they are ‘just about getting by’.

Paradoxically, as incomes are now starting to see real growth, the improvements in financial well-being are stalling. Within-wave analysis of Understanding Society suggests the picture was less positive in 2016, particularly for those on the lowest incomes. This appears to be in line with the latest messages from consumer confidence surveys and expenditure data.

It is perhaps surprising that the longest period of income stagnation has not led to greater feelings of financial difficulty. However, the relationship between income and financial well-being is not as strong as we may be commonly expected. Taking a broader view of living standards could help unlock greater insight into how best to help people and society react to changes in the economy.

__________

Note: the above draws on research which Kirby conducted together with Dr Matt Barnes, Lecturer in Sociology, and Nhlanhla Ndebele, PhD Researcher, both at City, University of London.

Kirby Swales is the Director of the Survey Research Centre at the National Centre for Social Research.

Kirby Swales is the Director of the Survey Research Centre at the National Centre for Social Research.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Pixabay (Public Domain).

Well I might today and have no job tomorrow.

Thus mean amount of employment in FTE and periodicity of employment are other parameters if financial security (fs)

Ergo

FS=FTE*salary +employment cycle length+sector durability+ savings-debt

I,m always amazed that the press reports 94% employment!!! or some such figure, whereas the FTE may be 83%. Doesn’t look quite so brilliant does it.

It would be interesting to factor in levels of debt. People can and often do drift along on a cushion of debt that provides an illusion of financial security in that they’re getting by pretty well in the short term. It would be interesting to plot the overall sense of financial well being against overall household debt levels. I suspect there would be a correlation. It plays well to political short-term thinking if so. Is debt the key to 21st-century economic cycles? Turn a blind eye to it until everything collapses, be ‘amazed’ when it does, then start over? If so, the overall trend can only be downwards. The comparative rise of China and other nations’ middle classes may be as much to do with the general decline of traditionally developed nations as the up-and-coming nations’ own improvement. Much easier to win a race to the top if your competitors are fading.

Have you got an equivalent graphic for financial well being vs wealth? I am no expert in this field, but I can imagine that those of any income level with some cushion against shocks may feel able to cope with low, uncertain or changing income, whereas those with no savings at all (quite a lot of people) are likely to feel financially insecure at almost any level of income.

In answer to the question posed the answer is simple, No