Developments in London’s financial district help us understand the precise form that Brexit will take, argues Sarah Hall. She explains why London is distinct to the rest of the UK and writes that, as companies threaten to move to other European cities in anticipation of a ‘no deal’, the government’s decision making is still not reflecting the City’s strategic importance.

Developments in London’s financial district help us understand the precise form that Brexit will take, argues Sarah Hall. She explains why London is distinct to the rest of the UK and writes that, as companies threaten to move to other European cities in anticipation of a ‘no deal’, the government’s decision making is still not reflecting the City’s strategic importance.

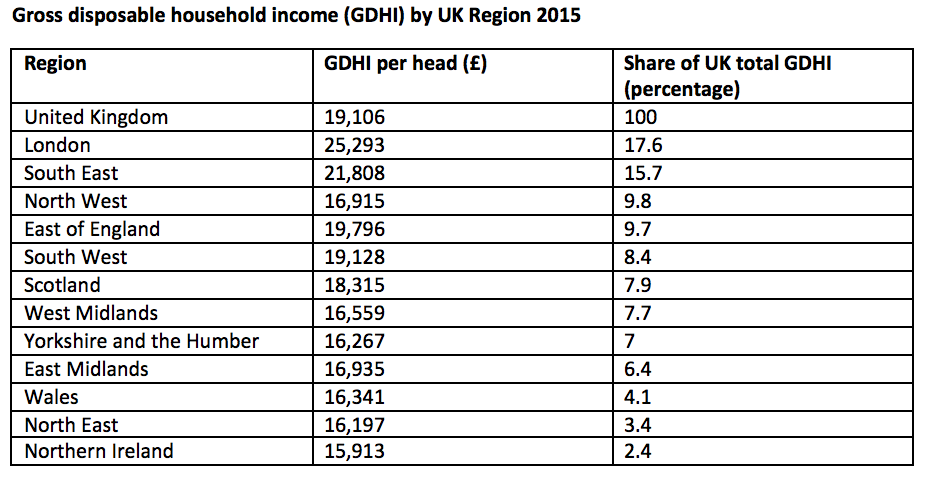

London, and its financial services sector in particular, provides vital insights into understanding England’s Brexit vote in June 2016. Economically, politically, culturally and socially, the capital’s 8.7 million residents are increasingly characterised by their distinctiveness as compared to those living elsewhere in the UK – a trend that has intensified following the financial crisis of 2007-8. For example, figures from the Office for National Statistics show that even after accounting for higher housing costs, gross disposable household income was highest in London in 2015 at £25,293 compared with £16,197 in the North East of England and £15,913 in Northern Ireland.

For the full data see here.

For the full data see here.

Meanwhile, the Centre for Cities revealed the extent to which the UK relies on tax receipts from the capital arguing that London generates 45% of the taxes generated in urban areas in 2014/15 equivalent to almost as much tax as the next 37 cities combined.

The distinctiveness of London in relation to the rest of the UK was also clearly demonstrated in the Brexit vote. London was one of a handful of predominately University cities to vote remain in the referendum in June 2016. This reflects the comparatively high levels of migration coupled with relatively strong economic growth enjoyed by Londoners. However, in contrast, the success of London relative to the rest of the UK was also important in driving the ultimately successful Leave vote. For authors such as Danny Dorling, this vote was driven by growing inequality following a prolonged period of austerity politics that have resulted in worsening health outcomes and declining living standards for many British citizens who wanted someone or something to blame.

In the two years since the vote, London’s distinctiveness has become increasingly significant in relation to the future development of the UK’s economy after Brexit. This stems from the fact that the economy relies on the service sector which makes up 79.6% of the UK’s GDP and is driven by financial services in London’s international financial district. Indeed, financial and related professional services – such as legal services and the insurance sector – which are overwhelmingly concentrated in London make up a significant part of this, accounting for 6.5% of UK economic output in 2017. However, the impacts of Brexit on the strategically important financial services sector are best characterised by profound uncertainty with potentially significant implications for the future trajectory of the UK economy.

There are two main causes of this uncertainty. Firstly, despite the rapidly approaching negotiation deadline, the precise nature of Brexit remains unknown. What is clear is that the financial services sector at the heart of London’s economy will not be given the special privileges that it has previously enjoyed in times of significant change. For instance, in the 1990s, the impact of joining the Euro on London’s financial district was singled out as a key criterion used in government decision making, reflecting the City’s strategic importance in the UK economy. Compare this with the 2017 New Industrial Strategy that makes very little mention of the financial services sector, viewing it far more as a way of facilitating growth in other economic sectors, particularly manufacturing.

The second uncertainty in understanding the impact of Brexit on the UK’s economy, and the role of London within this, lies in the relationship between the UK’s financial services sector and the international financial system. We now understand this relationship as highly complex and interwoven. This means that the impact of any Brexit deal on one particular part of London’s financial services ecosystem could have profound, but unpredictable, implications elsewhere in the system. As the Chairman of HSBC summarised to the Treasury Select Committee in 2017 “the ecosystem in London is a bit like a Jenga tower. We don’t know if you pull one small piece out, whether nothing happens of indeed if there is a more dramatic impact”.

These uncertainties have not been resolved in the keenly-awaited publication in July 2018 of the UK Government’s White Paper on ‘The Future relationship between the United Kingdom and the European Union’. On the critical issue of financial services, the White Paper recognises the interconnected nature of financial networks between the UK and the EU, but proposes a relatively unspecified “new economic and regulatory arrangement with the EU in financial services” that would “maintain the economic benefits of cross-border provision of the most important international financial services traded between the UK and the EU”.

Crucially, the Paper does not call for mutual recognition for financial services between the UK and the EU. Mutual recognition provides greater certainty than other trade options for the relationship of financial services in the EU and UK because it operates on the basis that products developed in one country can be sold across all EU member states. Reflecting his calls for a softer Brexit, the Chancellor of the Exchequer had been advocating for mutual recognition for the financial services sector following the Brexit vote, most recently at his annual Mansion House speech in June 2018.

In contrast, and reflecting the fact that the financial services sector will not be singled out for special treatment within the Brexit negotiations, the Paper argues for a broader form of equivalence between financial services in the UK and EU. Typically, equivalence creates more uncertainty in trade relations because decisions on equivalence are unilateral. In this scenario, each trading partner is able to make a decision (and withdraw this) as to whether regulations in the trading relationship are the same, thereby allowing goods and services to be traded between the two parties. In order to address this, the UK Government states in the White Paper that for financial services, it seeks to develop a “reciprocal recognition of equivalence” although the precise mechanisms through which this would be developed and implemented remain far less certain.

It is this ongoing uncertainty that could have a bigger part to play in shaping the UK-EU trade relationship in financial services post Brexit than policy and regulatory pronouncements. The pace of London’s financial markets move markedly faster than that of Brexit negotiations to date. The uncertainty surrounding Britain’s future relations with the EU is already leading to a growing sense amongst financial institutions that it is prudent to take action now in readiness for a ‘no deal’ in which agreement can’t be reached by the March 2019 deadline. For example, within hours of the White Paper’s publication, the Chief Executive of Lloyd’s of London argued that the uncertainty would lead to the firm going ahead and opening a planned subsidiary in Brussels. Part of this relocation activity is to act as a lobbying force, essentially sounding a warning shot to negotiators that if the financial services sector in London does not get the type of Brexit it wants, it will take action accordingly.

Whilst the precise implications of such actions remain unknown, both in terms of any deal ultimately struck and the trajectory of London’s international financial district, it makes it clear that understanding what is happening to the City will be vital in understanding the precise form that Brexit takes. Moreover, the uncertainty of the negotiations now extends beyond the nature of financial services relations between the UK and the EU to a wider questioning of the position of London’s financial services sector economically and politically within UK plc.

________

Note: the above draws on the author’s co-authored work (with Professor Dariusz Wójcik) published in Geoforum.

Sarah Hall is Professor of Economic Geography at the University of Nottingham.

Sarah Hall is Professor of Economic Geography at the University of Nottingham.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Pixabay/Public Domain

Max Frisch’s play “The Fire Raisers” is being reenacted on a grand scale including Biedermann’s inconsequential analysis.