While many presumed school attendance levels would recover rapidly from the impact of the pandemic, new research reveals the scale of continued absenteeism among school pupils across the country. Andrew Eyles, Esme Lillywhite and Lee Elliot Major outline their findings and discuss the difficulty of tackling this problem at its root.

One of the most damaging legacies of COVID-19 may yet prove to be the unprecedented closure of the nation’s schools during the pandemic. In March 2020, most schools across the UK closed their gates. Millions of pupils headed home with little idea of how they would continue their studies.

When we produced initial estimates of the large learning losses likely to be suffered by the COVID generation of pupils, many dismissed these calculations as scaremongering; they argued this would just be a one-off disruption and pupils would soon bounce back. However, new data we present here for England sadly shows this is not the case. We now face a national education crisis in the post-pandemic era: a huge slice of the COVID generation have never got back into the habit of regularly attending school.

A huge slice of the COVID generation have never got back into the habit of regularly attending school.

The rise in absenteeism among pupils has been startling. During the autumn term of 2017/18, 4.4 per cent of lessons were missed across state-maintained schools; during the autumn term of 2021/22, 6.9 per cent of lessons were missed. Meanwhile there has been a staggering increase in persistent absence. In 2017/18, 11.7 per cent of pupils missed 10 or more sessions (defined as half a day of school); in 2021/22, 23.5 per cent of pupils missed 10 or more sessions.

A crisis affecting children across the country

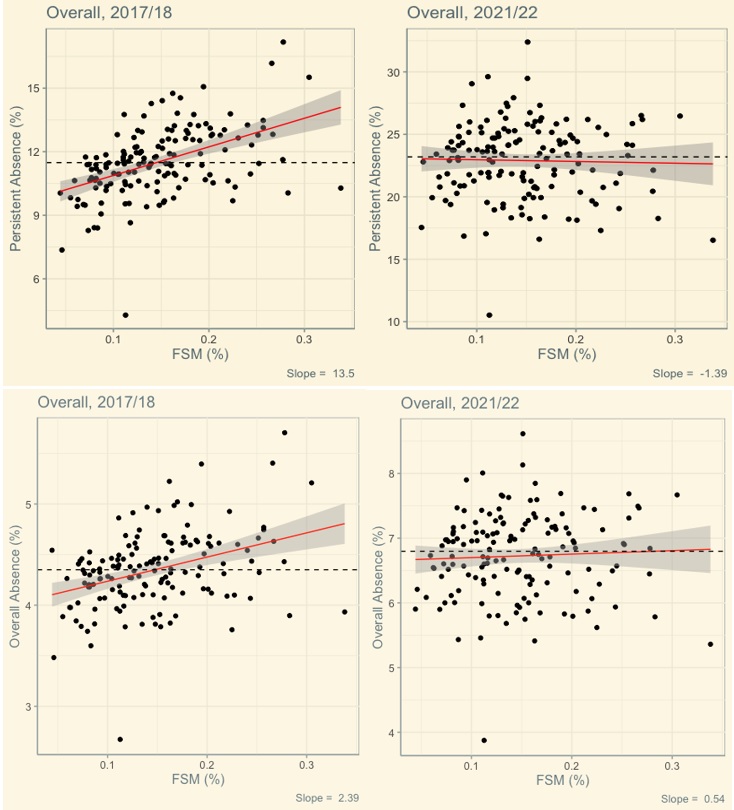

Our figures also show how widespread absenteeism has become across the pupil population. Primary and secondary school pupils are missing school across all areas of the country. The rising tide of absences has eradicated a once strong statistical correlation between local deprivation and absence rates. Figure 1 below plots the relationship between absence and the proportion of pupils eligible for free school meals (FSM %) at the local educational authority (LEA) level. In 2017/18, the rate of persistent absenteeism was 24 percent greater in the most deprived areas compared with the least deprived areas. In the post-pandemic era, we find no evidence of such a difference when we compare the bottom and top deciles of areas by deprivation.

When we look at individual pupils, a similar story emerges. Overall, the number of pupils classed as persistently absent rose from 921,927 to 1,672,178 between 2019/20 and 2021/22. Breaking this down by FSM status, the rate of persistent absence doubled for non-FSM pupils across the country, going from 10.5 per cent to 20.0 per cent. In percentage terms, this far outstrips the rise amongst FSM pupils from 23.8 per cent to 33.6 per cent.[1]

Similar results hold for overall absence which increased from 4.3 per cent to 6.0 per cent for non-FSM pupils (a 40 per cent rise) and 7.6 per cent to 9.7 per cent for FSM eligible pupils (a 28 per cent rise).

Notes: The above derives from the authors’ own calculations based upon data available here and FSM variables taken from school performance tables. The red line is a fitted regression line (unweighted) based upon the relationship between the fraction of pupils eligible for FSM and the rate of persistent (and overall) absenteeism at the LEA level. The dashed dotted line refers to the national mean. The data are for those in state maintained schools – both primary and secondary level. The findings above hold separately for primary and secondary and are not sensitive to the base period – in this case 2017/18 – chosen.

These patterns mirror those we have observed in previous work. For example, we found that educational losses were widespread during the pandemic and not confined solely to children with the least resources. It appears that the most privileged children are being insulated from the damage impacting the rest of the population, rather than the poorest pupils falling further behind everyone else. Other research has shown that children in state comprehensives are twice as likely to say they have fallen behind in the studies than privately educated pupils (15 per cent vs 37 per cent).

The challenge of finding solutions in uncharted territory

The reasons for the rising absences are still unknown. Increased anxiety, lack of mental health support, and budget pressures have been cited, as have changes in parental working schedules. We have previously suggested more fundamental factors could be at play: a breakdown in trusting relationships between parents and teachers alongside increasing unhappiness with the narrow academic curricula schools are measured by.

It’s also far from clear what will persuade students to come back to school. On May 18, the government announced plans to tackle absence rates by expanding Attendance Hubs and Attendance Mentor programmes. These will share effective practice such as automatic texts to parents of chronically absent pupils. Interventions such as these are not unprecedented, but the nature of the problem is. A recent review by the Education Endowment Foundation highlights that sending parents personalised letters or texts can help improve attendance, but it is not obvious that interventions such as these will work at scale if the composition of those absent – and the reasons for that absence – are different to what they have been in the past.

Improving attendance needs to be part of a longer-term education recovery plan

In our view improving attendance needs to be part of a longer-term education recovery plan, one strand of which should aim to forge deeper school-parent partnerships. We are still in the earliest days of comprehending the full impact of the pandemic on the COVID generation. Our work supported by the Nuffield Foundation will shed more light on this, assessing the lasting impacts on school attainment and non-cognitive skills for pupils at different ages and academic levels. The aim is to help inform governments to develop the most effective ways of improving prospects for a generation facing multiple challenges including a sclerotic labour market, stagnant productivity growth, and rising costs of goods – particularly housing – that are essential for a good standard of living. Getting children back to school would be a good start.

[1] This paragraph refers to results using 2019/20, rather than 2017/18, as a baseline due to information on absence breakdowns by pupil characteristics only being available from 2019/20.

This research is part of COVID-19 and social mobility: life prospects in a post-pandemic world, a project supported by the Nuffield Foundation.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: Marco Fileccia via Unsplash.