Brexit has forced European decision-makers to take stock of the EU integration process. Dennis J. Snower writes that Brexit should be viewed as only the latest symptom of a process of social disintegration across Europe brought on by the impact of globalisation. He argues that Europe is now at a dangerous point in its history and that feelings of exceptionalism, victimhood and disaffiliation must be tackled to reverse the current trajectory.

Brexit has forced European decision-makers to take stock of the EU integration process. Dennis J. Snower writes that Brexit should be viewed as only the latest symptom of a process of social disintegration across Europe brought on by the impact of globalisation. He argues that Europe is now at a dangerous point in its history and that feelings of exceptionalism, victimhood and disaffiliation must be tackled to reverse the current trajectory.

Brexit has put Europe on a dangerous course. Europe has been here before, but, for most of its people, such periods of turmoil took place too long ago for them to be personal memories. Nevertheless, the early symptoms of the crisis are recognisable.

First, there is a large and growing segment of the disadvantaged – regular people, doing routine jobs – that finds itself unable to participate in the fruits of globalisation. Meanwhile an identifiable segment of advantaged people, benefiting from globalisation, are cushioned from the insecurities of the disadvantaged.

There is a growing perception by the disadvantaged that their failures and insecurities are due to external circumstances – the financial crash of 2008 and tax-financed bail-outs followed by austerity measures hitting regular people. This is leading to a rising sense of disempowerment. Alternatively, there is a growing perception by the advantaged that economic and social successes are attributable to personal achievements.

There is presently blind opposition to an increasingly ineffective governance structure – the apparatus of Brussels – which is deemed remote, overbearing and illegitimate. Alongside this is an indifference to the veracity of political pronouncements, fuelling a cycle of mistrust and alienation. And there is a sense of impatience with liberal democratic processes, including checks and balances, as well as safeguards for the protection of minorities.

A sense of social exceptionalism, leading to greater importance being attributed to cultural or national identities, is beginning to dwarf the importance of economic issues. The situation has cultivated a sense of victimhood, enabling the disadvantaged to ascribe their misfortunes to others, and motivating a general search for scapegoats.

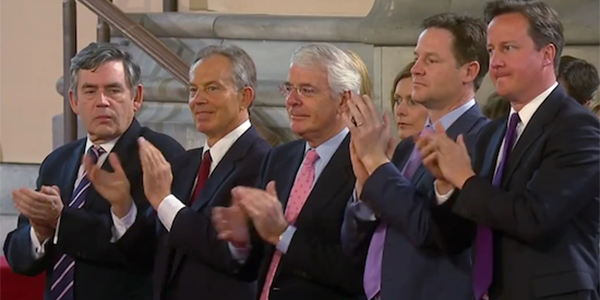

The rising appeal of populist politicians and media who give legitimacy to expressions of narrow nationalist or cultural sentiments is a symptom of this. There is now a broad disaffiliation from people who are different in terms of culture, religion, ethnicity or nation, manifesting itself in a withdrawal of tolerance, respect, consideration and empathy for foreigners; while the scapegoating of foreigners and a desire to purify oneself from their influence has become prominent.

Social disintegration

It is tempting against this backdrop to draw parallels with the Europe of previous generations. We have seen this kind of phenomenon before: in many respects these developments were the social face of fascism in the early to mid-20th century. Today we tend to associate fascism with its political face: the mere mention of the word conjures up images of authoritarianism, dictatorships, corporatism, right-wing stances and militarism. But this acts as a way of disassociating ourselves from the same forces by projecting them on to the interwar period and the governments responsible for the Second World War. In doing so, we have blinded ourselves not only to the social basis that fascism was grounded in, but to the relevance these social forces continue to have for contemporary politics.

The most important of these social forces are exceptionalism, victimhood and disaffiliation. They are interrelated. In the simplest terms, we think we are superior to others, but we are victims of other groups who seek to take advantage of us; thus we sever our affiliation to the others, enabling us to be unmoved by their joys and sufferings. This leads inevitably to social conflict.

In the UK itself, reports of hate crimes rose substantially in the aftermath of the Brexit vote, reflecting a rise in hostility to migrant groups, including verbal abuse, racist graffiti, social media abuse and physical assaults. But this certainly does not mean that all Brexit voters are racists. On the contrary, most are undoubtedly well-meaning, hard-working British citizens with strong loyalties to their country’s traditions of fair play, trustworthiness and civility.

Those who face hopeless job prospects, despite their best efforts, have reason to be angered that they have been excluded from prosperity. They are, by and large, good and honest people, who are powerless not only economically, but also socially. They are caught in social pressures that arouse their sense of identity and sovereignty. Against this backdrop, who they really are has become more important than how much they earn. These pressures encourage them to define themselves in opposition to people who do not share their heritage. The result is that some people have been led into social conflicts that they generally cannot foresee.

Undoubtedly, the Brexit vote would not have been achieved without a sense of British exceptionalism, without a sense that the country is being undermined and exploited by other groups, and without a psychological disassociation from foreigners. These forces have been awakened with a vengeance in many other European countries. In France, Marine Le Pen is riding this wave of discontent. Her declaration, ‘Long live free nations! Long live the United Kingdom! Long live France!’, makes this clear. Some polls suggest that she now may have a realistic chance of winning the presidential election. Her anti-immigrant, anti-Brussels, Front National is the most popular party among the working classes.

Austria also faces a rerun of its presidential election, nearly won last time by a right-wing, anti-immigrant candidate. In the Netherlands, Geert Wilders’ Party for Freedom, also opposed to immigrants and Brussels, leads in the opinion polls. Italy faces political and economic turmoil, with Matteo Renzi fighting for his political survival and the anti-Brussels Five Star Movement winning control of Rome and Turin in recent mayoral elections.

These social forces are also present in the successes of Donald Trump in the US, and the popularity of Vladimir Putin, alongside the increasingly harsh and ruthless relations among differing ethnic and religious groups in the Middle East and Far East. Suddenly the geopolitical world is looking increasingly unstable, propelled toward internal and external conflict through the grievances of the powerless classes and the indifference of the advantaged.

A time for action

The time has come for us to awaken from this impending nightmare. We have already seen where it can lead. It is high time we address its root causes. Integration of the global economy cannot succeed without some form of social integration. It is not sufficient for globalisation to raise average incomes in a country. Each EU member state requires employment, training, education and social security systems that permit the benefits from globalisation to be reaped by all citizens. We must dismantle policies that permit advantaged segments of the population to become sequestered from the fortunes of their country.

Politicians and the media must also avoid pretending that social and economic success is always a measure of personal achievement, thereby legitimating the status quo. Nor must they pretend that social and economic failure is always a product of external circumstance, thereby disempowering the disadvantaged. We must get serious about creating equal opportunities for all our citizens, continually challenging the power of special interests, and dismantling the protection of insiders at the expense of outsiders.

Ultimately, the EU needs to ensure that its initiatives for political and economic integration are matched by initiatives for social integration. This means giving all school leavers the opportunity to work in other EU member states, eliminating obstacles to labour mobility for all working-age citizens of the EU, promoting the portability of welfare benefits and pensions, and encouraging wide-ranging cultural exchanges.

After all, there are two potent ways to overcome the plague of exceptionalism, victimhood and disaffiliation: to promote equal opportunities and to bring people into contact with one another in settings that help them understand each other’s perspectives.

______

Note: This article was first posted on EUROPP – European Politics and Policy.

Dennis J. Snower is an American economist and President of the Kiel Institute for the World Economy, Professor of Economics at the Christian-Albrechts University in Kiel Germany, and President of the Global Economic Symposium. One of focus of his current research is to extend the domain of identity economics.

Dennis J. Snower is an American economist and President of the Kiel Institute for the World Economy, Professor of Economics at the Christian-Albrechts University in Kiel Germany, and President of the Global Economic Symposium. One of focus of his current research is to extend the domain of identity economics.

I am impressed by this article and its search for root causes and patterns. The suggested solution is in synch with that from the Brexit cause and effect model on know-why.net.

With regard to the root causes and the effects that an improved interchange should offer I would like to point to chance of a non-materialistic integration of different parts of Europe’s societies.

Now that Fareed Zakaria also argued that way I have developed a cause and effect model covering the major arguments: https://www.know-why.net/model/CWejwGHa-455h-YLP7W9_rw

Thank you for sharing your thoughts on this critical issue. The EU faces a set of daunting economic, security, political and social problems which are closely related and reinforcing each other. However the problem of social disintegration is most dangerous as it threatens its social fabric and core values the union has been build upon. All the rest make little sense if social integration—as within so between member nations—fails.

(1) I fully agree with the root causes you have identified. And true, this didn’t happen overnight. Whatever ironical it may sound, a sequence of ill-thought-out strategies and related policies (approximately since the end of Cold War) has resulted in the EU increasingly resembling the features of an empire in decline: Accelerated albeit unfeasible territorial expansion at the expense of gradual progression; Inequality in wealth distribution, as between the centre and the peripheries so within each country; Mass migration from the peripheries to the centre combined with the tense intergroup and interfaith relations; Poor overall economic performance, especially vis-à-vis aggressive external competition; Inflexible decision making processes combined with diminished government effectiveness; Sizeable and quite expensive central bureaucracy; The rise of radical political movements and disintegrative forces; and The escalating security threats.

That said, I think that the problems in and of Europe are not all exclusively due to EU’s failures; national governments shall accept their part of responsibility, too.

(2) A two-way path toward overcoming the problem you have offered—to promote equal opportunities and to bring people into contact with one another—also seems the only reasonable solution. European Union was designed as an evolving institutional arrangement where integration should be treated as means to an end and not the final destination; and therefore, the solution is not in integration but through integration (and associated inclusion, trust, fairness).

As for implementation modality, I would advocate for avoiding grand projects and ambitious all-encompassing policy endeavours but instead adopting a strategy built on continuous adjustment and refinement—through small and inclusive (often-time grassroots) initiatives, experimentation and learning, and eventually adapting. There are multiple advantages to this approach, along with significantly increased chances of solving this problem eventually. One is that, performing in this mode Europe would remain dynamic, resilient, and relevant and adequately equipped to face the challenges of fast-progressing environment while preserving its core values.

The inconvenient truth of present day globalisation.

Within the context of historically created structural imbalances within our global society, we are seeing disproportionate levels of resource flows both within and between developed and developing countries. As a result, global development has been and still is very uneven. Therefore, whilst developed countries continue to receive a greater proportion of capital and financial resource flows, these same developed countries are financing …

1. Land-grabbing initiatives in developing countries in order to promote industrial agriculture for bio-fuels and foodstuff

2. Conservation programmes which are being used as an opportunity by developing countries to promote economic growth through tourism (including big-game hunting) and precious mineral extraction

3. Free trade agreements which leads developing countries to restructure their economies to satisfy consumerist demands within developed countries.

These investment progrqmmes are all of resulting in the forced eviction of indigenous tribes and rural dwellers from their ancestral homelands resulting in rapid and unmanageable urbanization, a loss of biodiversity including wildlife habitats, soil and atmospheric pollution and increased greenhouse gas emissions through increased industrial production leading to climate change.

The conundrum for developing countries and for global society as a whole is that whilst these structural inbalances persist then developing countries are effectively being forced into ecologically damaging practices as their only means to economically grow. Incidentally, the same ecologically damaging practices that enabled developed countries to economically grow.

The negative impacts of globalisation in the form of forced evictions of indigenous communities and subsistence communities from the rural to the urban and the rapid urbanisation of developing countries is leading to multiple territorial conflicts as this rapid social change invokes differences over race, class and ethnicity in relation to scarcity and growth opportunities. Similar conflicts and tensions are emerging in developed countries as uneven development and scarce growth opportunities results in increased labour flows into developed metropolitan areas. Therefore whether within the context of developed or developing regions, to varying degrees, public infrastructure is under-resourced to provide the necessary capacity to avoid these tensions and conflicts.

Overall, the structural inbalances within our global society underpin a lack of infrastructural capacity to accommadate the rapid social change that is being created through globalisation. This is felt most intensely in developing countries which is creating the conditions for mass migration, not only into adjoining countries that are relatively more developed but also towards the developed West. To a lesser degree, these same structural inbalances are at work within developed continental regions which is similarly creating mass migration tendencies but to a lesser degree but with the same problems associated with inadequate infrastructural capacity.

So essentially, at present we have a historically created situation whereby a lack of global cooperation to manage capital and financial resource flows in order to better diversify and distribute economic growth opportunities is causing mass migratory tendencies at all regional scales within global society. In turn, as a result of inadequate infrastructural capacity, this is leading to a tense environment of ‘unmanaged’ competition over scarcity and growth opportunities and the need to ‘manage’ these tensions with a policy of cosmopolitan equality which results in the hollowing out of indigenous traditions and accustomed lifestyles.

Effectively therefore, present day globalisation is a process of violating or ignoring internationally agreed human rights frameworks which then leads to state (or civic) enforcement of a rights-based cosmopolitan equality agenda in order to mitigate against the tensions that arise from these originating human rights violations.

To make matters worse, the underlying structural imbalances that have created this environment of poverty and scarce growth opportunities, which I argue is borne from a logic of competitive self-interest, is not only both encouraging the degradation of our ecological world and encouraging social change at an unmanageable rate but also the limited financial gains of this destructive form of globalisation is simply not adequate enough to pay for the huge expenditure that is required to increase the capacity of urban and peri-urban infrastructures in both developed and developing countries. In effect, due to competitive self-interest and the structural inbalances that this competitive self-interest promotes, we are creating an environment filled with multiple crisises at social, economic, ecological, political and cultural levels. In effect we are socially constructing a dystopia filled with strife and conflict at all levels of global society.

The only solution I argue is a globalisation that is based on cooperation rather than comoetition and one that is underpinned by an attitude of cooperative self-interest. Therefore with regards the EU for example, rather than advancing a highly competitive social market economy (TEU Art 2) it would be much more fitting of a civilised global culture to be advancing a highly cooperative social market economy instead (to be announced).