From the Covid inquiry, to the Royal Mail postmasters and the NHS infected blood scandals, Britain’s fragmented “integrity institutions” have repeatedly shown that they cannot prevent overt corruption and endemic malversation in public office. If a new Labour government is ever to “turn the page” on the the last decade, radical changes in institutional arrangements are needed, argues Patrick Dunleavy. A feasible solution is to establish a powerful Independent Commission Against Corruption and Malversation along Australian lines, with investigative powers and quick, significant sanctions.

Every liberal democracy relies for its survival on both macro-institutions (like free and fair elections, party competition, legislative oversight and civil rights) and a huge set of medium scale and micro-institutions regulating public officials’ adherence to a myriad of conventions, rules, and norms. These bodies are always scattered widely across the political and administrative landscape. Some may seem specific and far removed from democratic practices per se – covering detailed administrative decisions, regulations of industries, public procurement, and the “integrity institutions” specific to one policy sector. Tens of different such bodies already exist to enforce good behaviours and adherence to legal and ethical norms by public officials.

The 2018 Democratic Audit demonstrated that because ministers with a Commons majority have enormous executive powers, the UK has always been uniquely vulnerable to all its integrity protections being degraded by a determined government unconcerned about respecting past norms and ethical standards. Since 2019 the spiraling decline of the core executive into sleaze in all its forms has exceeded even the most pessimistic expectations, leading Transparency International to sharply downgrade the UK’s ranking. In addition, “malversation” – that is, misbehaviour in office, especially using public funds for private or partisan purposes (but falling just short of proven corruption) – has soared to unparalleled heights, often driven directly by Conservative ministers.

No decade in post-war British history has evidenced anything on the scale of this stunningly pervasive and serious collapse of ethical or public-interested central state governance.

A second source of peculiar vulnerability has been the UK’s tradition of refusing to codify standards of public conduct in any effective way, and a predilection for meeting each new problem by creating new, separate, and very weak “integrity agencies” – whose members are all appointed by ministers and whose “independence” can be suborned by them making just a few partisan appointments. Figure 1 shows a list of some of the most notoriously hopeless of these bodies alongside their failures to curb the scandals and malversation disasters with which they are now irretrievably associated. (The links behind the text here give more details). No decade in post-war British history has evidenced anything on the scale of this stunningly pervasive and serious collapse of ethical or public-interested central state governance.

Figure 1. Some of the UK’s failing ‘integrity’ agencies’ and the scandals they have failed to prevent

| Agency name

|

Key scandals and malversation disasters they failed to prevent

|

| Cabinet Office

|

– ‘VIP lane’ procurement rent-seeking by Tory MPs, peers and party donors- Cabinet Secretary role in enforcing ministerial code lapsed through inaction- ‘political’ Cabinet Secretary failing to enforce Cabinet Office propriety rules- vitiating entirely the role of ACOBA (– see below)- promoted Greensill’s influence within the civil service, and failing to ban direct lobbying by David Cameron, seeking to net himself around £20 million |

| Department of Health and NHS England | – Test and Trace procurement waste, at £ billions “unimaginable cost”- Protective equipment (PPE) procurement waste – cost £4billion

|

| Treasury | – Failure to curb VIP lane, PPE Test & Trace procurement waste (as above)- Eat Out to Help Out – £550 million restaurant subsidy hugely increased Covid 19 infections

|

| Treasury and HMRC | – Furlough fraud –lax ‘business-friendly’ implementation by ministers fake businesses & over-claims costing £4.5 billion

|

| National Audit Office and Public Accounts Committee | – Only documenting VIP lane, PEP and T&T scandals after they occurred – no pro-active moves to curb them during implementation.- No government follow-through on reports and ministers’ just denying findings.- Exclusion from investigation of Teesside Corporation

|

| Department of Housing and Local Government | – Robert Jenrick stayed on as minister after recusing himself after he admitted trying to fast-track a Tory donor’s housing scheme- Jenrick and junior minister granted Towns Fund monies to each other’s constituency while recusing on their own area- overtly partisan reprogramming of the Towns Fund and other grants to redirect money to non-needy Conservative seats- Predecessor departments (plus BRE etc) failed to regulate the fire safety of cladding at Grenfell Tower and other multi-story flats- caved in to overt lobbying by 1 in 3 Tory MPs who are private landlords to dilute and delay “no faults” evictions bill.

|

| Elections Commission | – Ministers weakened its powers, gaining effective control– Spending limits hugely increased, differentially benefiting Tory party- Voter ID implemented in partisan “voter suppression” ways- No action to update elections regulation for digital interference age

|

| Parliament | – record numbers of MPs since 2019 suspended by their parties for illegitimate or undeclared payments/jobs, or sexual misconduct- MPs still “give each other the benefit of the doubt” – tolerance of Johnson lying to the Commons about Partygate for months

|

| Independent Parliamentary Standards Authority | – Failed to regulate bumper outside earnings by MPs – £10 million in 2023 alone – or to enforce attendance at Parliament, service to constituency etc.- Can only advise – MPs themselves decide most cases still and have many immunities from police investigation

|

| House of Lords Appointments Committee (HOLAC) | – Complete inability to curb the overt and repeated sale of peerages to Conservative party donors- Could not exclude wholly unsuitable people as peers (e.g. those posing national security risks, with dubious business records, no evidence of distinguished public service, or those engaged in near-corrupt activities while remaining members.

|

| Independent Advisor on Ministers’ Interests | – Party appointee by PM, not independent and can look only at what PM says they can consider. Johnson completely ignored his, prompting their resignation. – Sunak’s wife’s massive shareholdings never checked.

|

| PM’s Anti-Corruption Champion | – Currently Tory MP, husband of former T&T head Diana Harding, and apparently inactive

|

| Ofcom | – Wrecked UK’s past impartial broadcasting rules by letting GB News funded by far right tycoon do whatever it likes to transmit only pro-Tory news– Caved in to ministerial pressure to appoint committed Conservatives like (Gibb) to BBC board

|

| BBC board | – Maintaining overt pro-Conservative government bias in most news outlets, after appointment of committed Conservatives to many news-related jobs.

|

| Ofwat | – “Capture” of Ofwat board and executives by water company interests and personnel- Initially debt-free water firms allowed to rack up debts of £72 billion to finance £85 billion in dividends and interest, bringing Thames verge of bankruptcy– Allowing companies to repeatedly and pervasively breach their legal obligations to not pollute rivers, streams and beaches with sewage- Allowing huge payments to executives and shareholders- Failing to require leak prevention, most new investment or new reservoirs in 20 years, despite major population growth

|

| Independent Advisory Committee on Business Appointments (ACOBA) | – Fake “independent” with Tory e-minister chair, and “anything goes” policy. Did advise limits on what Boris Johnston and some other ex-ministers could do – they just ignored it.

|

Achieving real reform

How can steps be taken now to effectively renew the public’s trust in central government elites, whether ministers, civil servants, agency staff and public contractors? It is easy to lapse into despair at the scale of the task ahead, or to believe that a little institutional tweaking is all that’s needed to rectify matters – as an ultra-complacent recent Institute for Government report on constitutional reform did. Labour has pledged a one-off Commissioner to investigate the Covid19 frauds over PEP, Ttrack &Trace and to try and claw back some lost monies.

Many political scientists now believe with Bo Rothstein that corruption is perhaps the biggest global threat to liberal democracy.

Yet the implications of Figure 1 above are that something wholly more thought through, integrated and clearly “turning the page” is badly needed. We also need to recognize that “corruption” is no longer typically organized now as a dyadic “quid pro quo”, but is instead operationalized as “malversation” in police-proofed triadic ways such as those shown in Figure 2. Once these powerful processes gain a foothold, they can easily be self-sustaining, and expand to become endemic and pose a major threat to the polity. Many political scientists now believe with Bo Rothstein that corruption is perhaps the biggest global threat to liberal democracy.

Figure 2 Examples of how triadic “malversation” stops just short of provable “corruption”, is self-fuelling and will become endemic unless stopped.

In Australia the incoming Labour government in 2023 reacted to a similar urgent need to improve public trust by pledging to establish a powerful National Anti-Corruption Commission with its own investigative staff and strong legal powers. Similar agencies have long existed in Australia’s state governments, and they have had huge impacts in improving previously flakey governance there. (E.g. the Independent Commission Against Corruption in New South Wales began investigating the state’s premier herself in 2022, leading to her resignation). That same commission is now moving ahead in Canberra.

Doing almost exactly the same thing in the UK would have a dramatic effect in strengthening the incentives for ministers, top civil servants, agency chiefs and regulators to behave in far more ethical ways. An Independent Commission Against Corruption and Malversation (ICACM) with its own investigative powers (including powers to investigate police corruption and malversation, a major problem in Britain still) and with the ability to call even ministers to answer for their actions, would be a revolution in improving integrity.

An ICACM would also create the “capstone” for a new and greatly strengthened ‘integrity’ regime across UK government. It would be key for its brief to include “malversation” as well as more obvious forms of corruption and for it to co-ordinate a collegium of integrity institution and agencies – including all those in Figure 1 for instance – so as to reinforce work on enforcing propriety and good governance across the whole state. Both the recent infected blood public inquiry and the still ongoing Covid public inquiry have demonstrated over and over again the need for a complete rethink of the rules of conduct for ministers, civil servants, regulators and agency heads. A great opportunity exists here to go back to the completed neglected but still worthwhile Seven Nolan Principles of “Selflessness, Integrity, Objectivity, Accountability, Openness, Honesty and Leadership”. But these rules would need to stop just being vaguely good ideas and become instead a strongly implemented, well-monitored and rigorously enforced Code of Ethics, applying by statute to all key public office holders.

A lot of detailed work remains to be done on reforms in this area by an incoming Labour government, whose core executive inner team (Keir Starmer, Sue Grey, Rachel Reeves and Pat McFarlane) has all the talents needed to ‘turn the page’. All the components for the transformation of UK central government back to a highly ethical mode of operating are feasible to implement in the government’s first two years:

– An Independent Commission Against Corruption and Malversation with its own statutory powers to investigate.

– A statutory Code of Ethics for all public office holders based on strengthening, implementing and policing in practice the Nolan Principles.

- – A Collegium of Integrity Agencies bringing together all the main bodies charged with maintaining good governance, under the leadership of the new ICACM.

Pledging this concerted action would combat a crisis of public trust and be an enormously popular move by Labour. It would powerfully attract Liberal Democrat, Green and moderate Conservative voters in seats where Labour needs their support to win. And in government establishing the new ICACM regime would quickly allow ministers, at very low cost, to show their supporters and the public at large that meaningful reform of government is underway.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

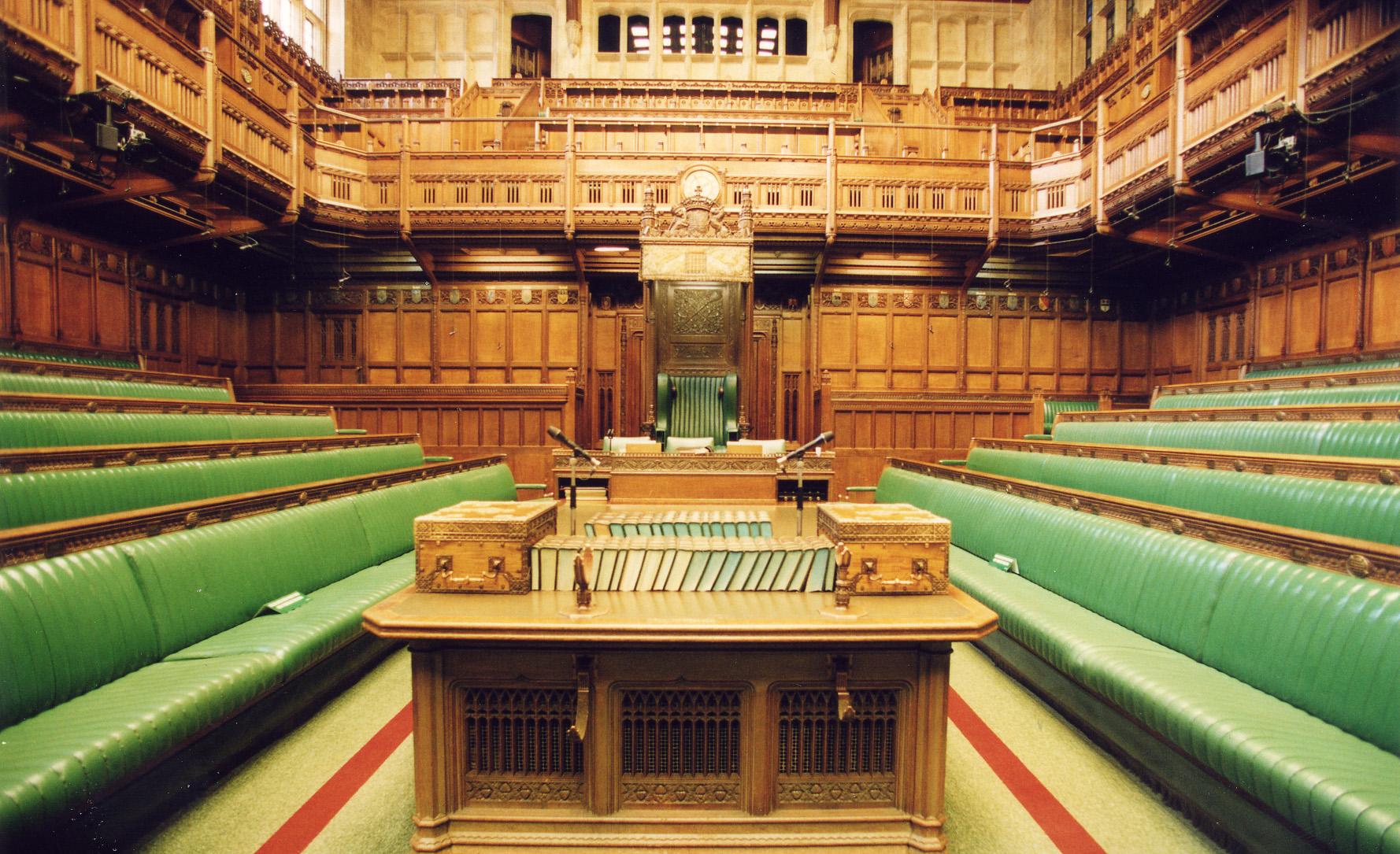

Image credit: Alex Yeung on Shutterstock