Since 1992, British governments have routinely published lists of cabinet committees. Nicholas Allen and Nora Siklodi argue that the latest list reveals much about the policy priorities and distribution of power in Theresa May’s government, and also provides a key insight into the new prime minister’s governing style.

Since 1992, British governments have routinely published lists of cabinet committees. Nicholas Allen and Nora Siklodi argue that the latest list reveals much about the policy priorities and distribution of power in Theresa May’s government, and also provides a key insight into the new prime minister’s governing style.

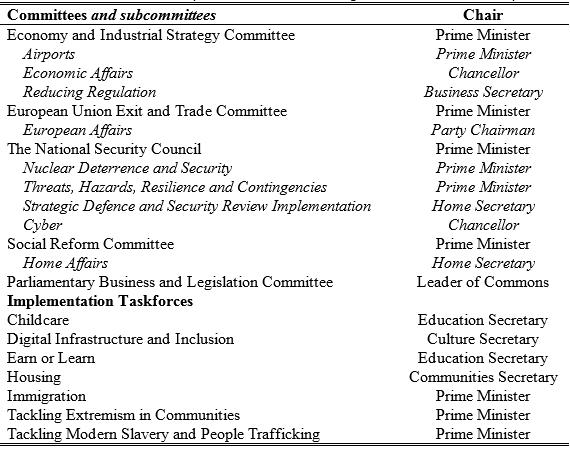

The right to create cabinet committees is an important source of prime ministerial power: prime ministers decide how to organise them, who to appoint to them, and how actively they are involved in them. May has streamlined the committee system she inherited from David Cameron. Instead of ten committees, ten subcommittees and eleven ‘implementation taskforces’ (bodies introduced in 2015 to drive forward the government’s ‘most important crosscutting priorities’), there are now just five committees, nine subcommittees and seven taskforces (see Table 1).

Table 1: Cabinet committees, subcommittees and implementation taskforces, October 2016

In addition to being streamlined, the system has also been restructured around four policy committees: Economy and Industrial Strategy, European Union Exit and Trade, Social Reform and the foreign-policy oriented National Security Council. There is also a fifth, largely procedural committee, Parliamentary Business and Legislation. Several long-standing committees, such as those dealing with economic, European and home affairs, have been reconstituted as subcommittees within the new system. Other long-standing committees, notably those focusing on constitutional affairs, public expenditure and Syria have been culled.

The quadripartite policy structure seems to reflect May’s reported preference for a form of ‘traditional cabinet government’, with an emphasis on collective decisions being made through formal processes. It also seems designed to facilitate prime ministerial oversight and influence. Existing and new subcommittees will presumably report to the relevant committees, all of which are chaired by the prime minister. May also chairs three subcommittees and three implementation taskforces that reflect her personal priorities or require her involvement for political or official reasons. Cameron, by contrast, chaired only two committees and two subcommittees when he first took office in 2010: one of these was the politically-oriented Coalition Committee, and the other three focused on national security.

Perhaps not surprisingly, press attention has focused on the membership of the European Union Exit and Trade Committee, which will oversee the Brexit negotiations. Six pro-Brexit cabinet ministers were appointed to this committee, including David Davis, Liam Fox, Chris Grayling, Boris Johnson, Andrea Leadsom and Priti Patel. Together, they constituted half the committee’s permanent membership. For proponents of ‘soft Brexit’, this development was taken as a sign that the government would press for a harder Brexit. From May’s point of view, it was probably necessary in order to manage the pro-Brexit wing of her government and, by extension, her parliamentary party.

Measuring positional power

Membership of a cabinet committee matters because it confers potential influence over decisions. The more committees on which someone sits, the more influence they potentially wield. At the same time, of course, some committees and some members of committees are more important than others.

These assumptions underpin attempts by political scientists to measure the ‘positional power’ of ministers on the basis of cabinet committees. Developed by Patrick Dunleavy, this measure first involves establishing the relative importance or ‘weighted score’ of each committee, which is a factor of their status and composition. Each committee’s weighted score is then divided among its members, with a greater share given to its chair. Finally, individual ministers’ shares are aggregated and reported as a percentage of all ministers’ weighted scores.

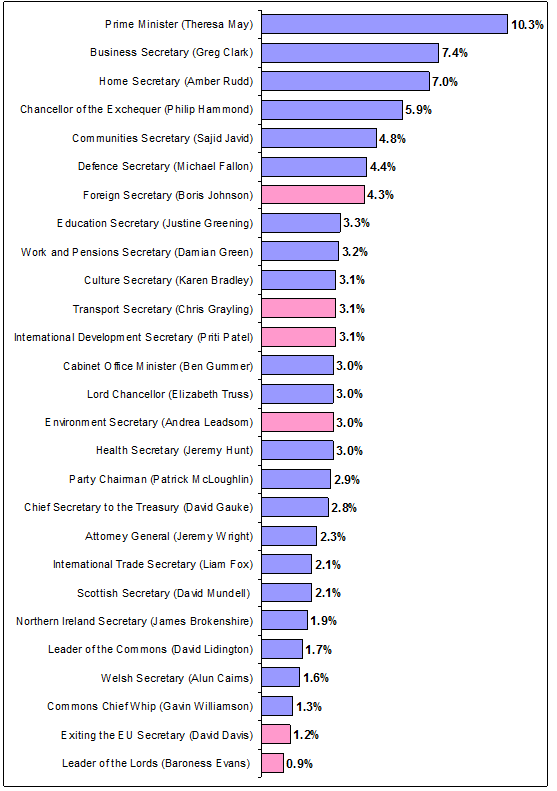

Applying the measure to the new list of cabinet committees enables us to explore further the distribution of power in Theresa May’s government (see Figure 1). The prime minister herself enjoys the largest positional-power score (10.3 per cent), ahead of Business Secretary Greg Clark (7.4 per cent) and Home Secretary Amber Rudd (7.0 per cent). Chancellor of the Exchequer Phillip Hammond has the fourth highest share (5.9 per cent) and Sajid Javid the fifth (4.8 per cent).

Figure 1 is also interesting for what it reveals about individual pro-Brexit ministers’ influence (represented by the pink bars). While these ministers enjoy a strong presence on the so-called Brexit committee, their potential influence in the broader committee system is limited. Boris Johnson has the highest score (4.3 per cent) among the pro-Brexit ministers—as Foreign Secretary, he sits on the National Security Council and its subcommittees—but he is the only such minister in the top ten. David Davis, the Secretary of State for Exiting the EU, has the second lowest score (1.2 per cent) among all cabinet-level ministers.

Figure 1: Cabinet-level ministers’ share of positional power, October 2016

Note: Pro-Brexit ministers are in pink. For the purposes of our calculations, taskforces have been treated as carrying the same weight as subcommittees.

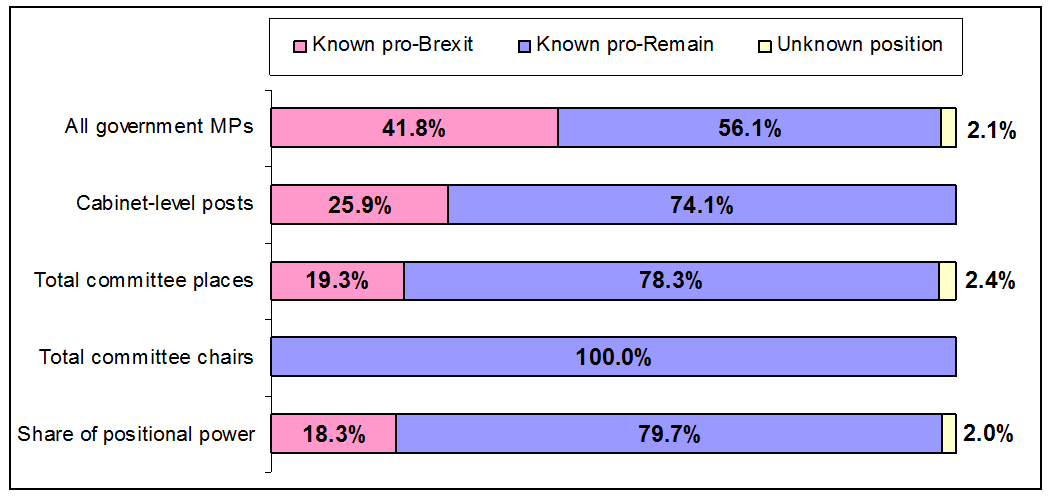

Figure 2 brings into sharper perspective the limited overall influence of pro-Brexit ministers in the cabinet-committee system. While over one-quarter of cabinet-level posts are filled by individuals who supported withdrawal from the European Union, they occupy just 19.3 per cent of all committee seats and not a single committee chair. The combined positional-power score for all pro-Brexit ministers is only 18.3 per cent, less than half the proportion of Conservative MPs (41.8 per cent) who took this position ahead of the referendum.

Figure 2: Positions on Brexit in the cabinet and its committees

Prime ministerial influence over time

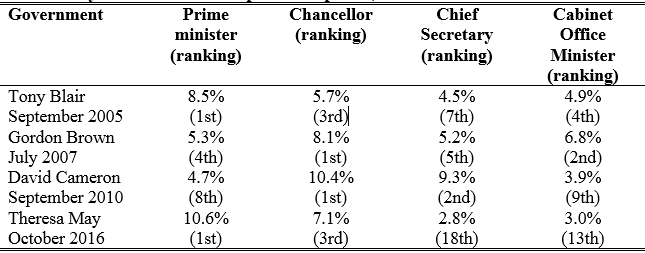

The advantage of using a consistent measure is that it also enables us to explore changes in positional power over time. Thus the final table extends our analysis backwards to compare May’s share of positional power with her immediate predecessors’. We find that she enjoys the highest positional-power score of any prime minister since at least September 2005, when Tony Blair was prime minister. Gordon Brown did not enjoy primacy in July 2007, whereas David Cameron’s share of positional power was notably meagre at the start of his premiership in 2010.

Table 2: Key ministers’ share of positional power, 2005-2016

Table 2 also serves to highlight two other features of May’s government. The first is the apparent downgrading of Treasury influence in the committee system, partly reflected in the Chancellor’s third-placed ranking in 2016 and especially in the Chief Secretary to the Treasury’s low score. Together, their potential influence is much diminished. This feature arguably accords with the abandonment of the old Cameron-Osborne narrative of austerity and its emphasis on fiscal rectitude.

The second feature is May’s apparent decision not to delegate supervision of the committee system to others. In recent years, Ministers for the Cabinet Office have been an almost ubiquitous presence in cabinet committees, helping to coordinate their work on the prime minister’s behalf. They have tended to enjoy accordingly high levels of influence. Cameron even appointed a second Minister of State in the Cabinet Office, Oliver Letwin, to share this role. Indeed, Letwin’s share of positional power in September 2010 (not reported) placed him third behind the Chancellor and Chief Secretary.

May, in contrast, seems to be relying largely on her chairmanship of the four key policy committees to supervise the cabinet. She is trusting in processes rather than people. This aspect of her leadership reflects her reputation as a details person and reluctance to delegate. Working in this way carries risks, however. On the one hand, insufficient delegation could lead to delays and the appearance of dithering, as reflected in the decision surrounding the Hinkley Point nuclear plant. On the other hand, while May’s style of government could lead to more deliberative decision-making in the spirit of traditional cabinet government, it could also lead to less predictable outcomes, especially if, or when, her authority begins to wane and her ministers have mastered their new briefs.

_____

About the Authors

Nicholas Allen is a Reader in the Department of Politics and International Relations at Royal Holloway, University of London.

Nicholas Allen is a Reader in the Department of Politics and International Relations at Royal Holloway, University of London.

Nora Siklodi is Lecturer in Politics and European Studies in the School of Social, Historical and Literary Studies at the University of Portsmouth.

Nora Siklodi is Lecturer in Politics and European Studies in the School of Social, Historical and Literary Studies at the University of Portsmouth.

1 Comments