Voters typically want their elected representatives to have roots in their local area, yet a large number of British MPs lack close ties with their constituency. Drawing on new research, Rob Gandy, Philip Cowley and Scott Foster illustrate trends in localism among MPs between the 2010 and 2019 general elections.

Voters typically want their elected representatives to have roots in their local area, yet a large number of British MPs lack close ties with their constituency. Drawing on new research, Rob Gandy, Philip Cowley and Scott Foster illustrate trends in localism among MPs between the 2010 and 2019 general elections.

For British MPs, being ‘local’ is generally recognised as having some electoral advantage because voters want their elected representatives to be local to their constituency. The UK has the fewest parliamentarians with local roots compared to other European countries. Yet the practice of ‘parachuting’ candidates into (seemingly) safe seats continues; as witnessed by the Wakefield Labour Party executive committee walking out of the hustings and senior Conservative Party officials ordering their candidate in the North Shropshire by-election not to speak to the media because he knew so little about the area.

The definition of ‘local’ is open to multiple definitions: place of birth; schooling; residence; place of employment; and even dynastic links where parents or grandparents held a seat. In a new study, we assess the regional roots of British MPs using place of birth, which has the advantage that it cannot be altered to make a candidate appear more electorally appealing.

We base our study on the twelve standard regions and nations, analysing whether a candidate was born in the same region as their constituency (which is reasonable given the chances of someone being able to represent the exact constituency in which they were born is dependent upon how ‘safe’ the seat is and whether a person’s politics coincide with that of the incumbent party). The goal was not to argue for a particular definition of ‘local’, but to analyse the extent to which British MPs are becoming more or less local over time and to try to tease out what is driving that change. Therefore, the precise definition used matters less than the trends over time.

Our results cover the period 2010-2019, which was politically volatile, seeing: a Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government in 2010; the subsequent electoral collapse of the Liberal Democrats; the Scottish independence referendum and rise of the Scottish National Party; the rise of UKIP and the Brexit referendum; the resultant negotiations with the EU and the emergence of a political divide based on ‘Leave’ and ‘Remain’.

There were historically high numbers of MPs switching parties during this period, especially after 2017, as well as significant changes in the make-up of the House of Commons. The most dramatic were the increased number of SNP MPs, the fall in the number of Liberal Democrats in 2015, and the collapse in the number of Labour MPs in 2019. These electoral shifts affected the degree to which British MPs were local across the decade, with clear increases in the proportion of British MPs with local roots. There were changes at each election, with newer cohorts of MPs being noticeably more local than the MPs they replaced.

Main results

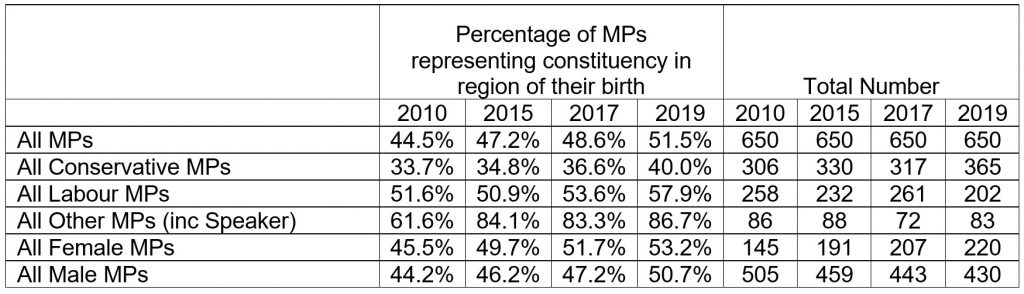

Tables 1-3 below show the percentage of MPs who represent a constituency in the region of their birth. Table 1 focuses on the main political parties and the sex of the MPs. It is seen that between 2010 and 2019 the overall figure for local MPs rose by seven percentage points, with more than half of British MPs being local by 2019. In all four elections, Labour had a greater percentage of local MPs compared to the Conservatives, although both major parties saw roughly equal rises in the percentage of local MPs over the decade.

The largest increase in local MPs was for the other parties, but this was mainly due to the rise of the nationalist parties in Scotland and Wales, and the Liberal Democrat losses in 2015. There was little difference between the sexes: female MPs are marginally more local than male MPs, but by 2019 just over half of MPs of both sexes were local. It was found that a little over half of male Labour MPs were local throughout the period, compared to an increase from 48% to 60% for their female counterparts. (At the same time women moved from 32% of Labour MPs to 51%). For the Conservatives the percentage of local MPs was very similar for both sexes throughout.

Table 1: MPs with regional connections, by party and sex, 2010-2019

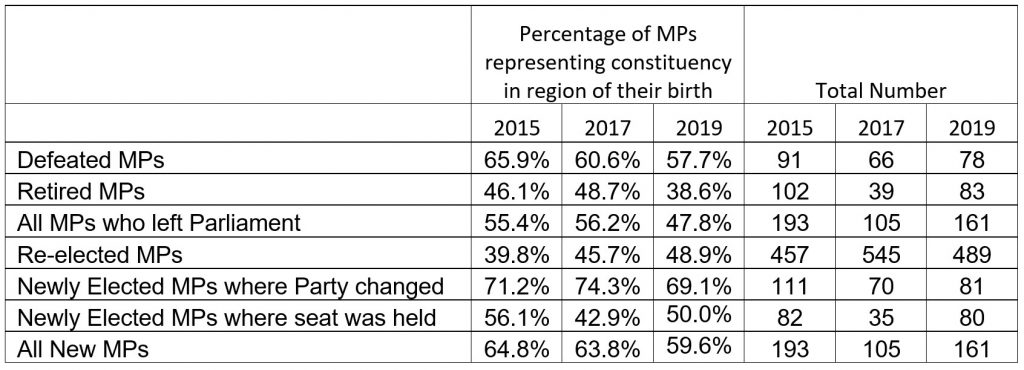

Table 2 examines the turnover of MPs. In 2015, 65% of new MPs were local, but those representing a seat where the party changed were noticeably more local (71%) than where the seat was inherited by an MP of the same party (56%). By comparison, only 40% of re-elected MPs were local. Of MPs leaving Parliament in 2015, 55% were local; with figures of 46% for those retiring and 66% for those defeated. The same general pattern holds true for both 2017 and 2019. In all three elections, new MPs who took a seat from a rival party were around 70% or more local.

Table 2: MPs with regional connections, by entry and exit to parliament, 2015-2019

Table 3 shows the decades of birth of MPs and the extent to which they are local. For each of the older (pre-1970) age groups, the percentages of local MPs were broadly similar up to 2017; generally, in the low 40s. Roughly half of MPs born in the 1970s were local. However, between 62% and 73% of MPs born in the 1980s and 1990s were local. The ongoing replacement of older, less local MPs with younger, more local MPs has had the greatest impact on the overall situation. For example, there were 102 (16%) MPs born in the 1930s and 1940s in 2010 but only 21 (3%) in 2019, which compares with 16 (2%) MPs born in the 1980s and 1990s in 2010 and 138 (21%) in 2019. Consequently, as older MPs leave the Commons, there should be further increases in the percentage of MPs who are local.

Table 3: MPs with regional connections, by date of birth, 2015-2019

Figure 1 shows the geographical differences for each of the four elections. The x-axis is the percentage of MPs in that region who were born within the region (i.e. the percentage of MPs in each region that are local). The y-axis shows the percentage of MPs born in a region who have a constituency in that region. A ‘self-sufficient’ region would have co-ordinates (100, 100); all MPs with constituencies in a region were born in that region, and no-one from that region represents a constituency outside the region. So, the nearer to the top right-hand corner, the more self-sufficient a region is. Scotland (93,71) and Northern Ireland (94,65) were the best examples in 2019.

Conversely, the nearer a region is to the bottom left-hand corner the more politician mobility is taking place; people from outside the region represent constituencies and natives leave their region of birth for other seats. London (45,32) and East of England (21,44) were the best examples in 2019. Regions below the 45° diagonal have more MPs born in them than there are constituencies, with the reverse the case for regions above the 45° diagonal. For illustration, in 2019 Londoners only represented 33 (45%) of the 73 London seats, whilst there were 70 (68%) elected to constituencies outside the capital. Over the decade, the changes in these geographical differences were mostly relatively minor, although (in line with the overall increase in local MPs) most regions saw their percentage of local MPs rise.

Figure 1: The regional mobility of MPs, 2010-2019

Conclusions

Relatively few seats change hands at each general election, even in an era of political turmoil: 281 constituencies (43%) were represented by the same MP in 2010 and 2019, and only 39% of these were ‘local’, as defined in this research. This compares to 61% for other MPs elected in 2019. There are clear partisan differences and a centre-periphery divide, but no overall gender divide. The trend towards increased (region-based) localism should continue on an evolutionary basis in coming elections as longstanding MPs retire or are defeated, to be replaced by younger, more local politicians.

This article is based on the authors’ work published in The Journal of Legislative Studies.

___________________

About the Authors

Robert J. Gandy is a Visiting Professor with Liverpool Business School, Liverpool John Moores University.

Robert J. Gandy is a Visiting Professor with Liverpool Business School, Liverpool John Moores University.

Philip Cowley is Professor of Politics at Queen Mary University of London.

Philip Cowley is Professor of Politics at Queen Mary University of London.

Scott Foster is the PhD Programme Leader at Liverpool John Moores University, Liverpool Business School.

Scott Foster is the PhD Programme Leader at Liverpool John Moores University, Liverpool Business School.

Featured image credit: Photo by Olivier Collet on Unsplash