The UK austerity programme promoted since the financial crisis energised a dynamic assemblage of political forces, aspiring to create a space of oppositional political identification. Sophia Hatzisavvidou writes that, although this anti-austerity campaign failed to rally voters in the last two general elections, we shouldn’t dismiss its impact on the country’s political life.

The UK austerity programme promoted since the financial crisis energised a dynamic assemblage of political forces, aspiring to create a space of oppositional political identification. Sophia Hatzisavvidou writes that, although this anti-austerity campaign failed to rally voters in the last two general elections, we shouldn’t dismiss its impact on the country’s political life.

Although the global financial meltdown of 2007–2009 started as a crisis of the banking system, it is until today widely presented and perceived as a sovereign debt crisis. Indeed, governments that opted for taxpayer bailouts to save the collapsing finance sector justified this form of state interventionism by presenting it as a necessary step for maintaining financial stability, supporting the wider economy, and responding to future financial crises. In practice, this interventionism entailed the imposition of fiscal austerity, namely of policy measures that cut the state’s budget in order to promote growth. This process was supported by the circulation of a rhetoric that argued for austerity as a form of conventional wisdom or common sense. According to this line of argument, austerity is the prudent choice of any government that aspires to keep the finances of the state on the track of growth.

In April 2009, David Cameron delivered a Party Leader Speech that neatly summarised what was to come, setting also the mood over how to understand what was gone: ‘The age of irresponsibility is giving way to the age of austerity.’ The Coalition government then adopted an austerity programme with welfare reforms that resulted in social benefits and pensions cuts, wage freezes, and public sector job losses, as well as measures that impacted on the governance of education, migration, and health. The impact of these measures has been profound: casualisation of work, inadequate funding of health services, and poverty. Following the creation of food banks, the appearance of clothes banks across the country marked a new point of deprivation, as it became increasingly evident that austerity measures hit not only those traditionally seen as more vulnerable but also those in stable employment.

Although anti-austerity campaigns and demonstrations proliferated since 2010, the result of the 2015 and 2017 general elections evidenced a failure of the agents of this oppositional movement to attract wider support and rally the public in a considerable electoral force. Nonetheless, electoral success is not the only way to assess political practices and their outcomes. If nothing else, the anti-austerity campaign curved a space for political identification from which it became possible to defy the TINA (There Is No Alternative) logic of austerity discourse.

One way to understand the workings of the campaign is by looking at how this diverse political movement communicated its message. Despite their ideological differences, political actors such as UK Uncut, the People’s Assembly, Scotland United against Austerity, the Radical Assembly, community run campaigns, as well as Plaid Cymru, Left Unity, SNP, and the Green Party became agents of anti-austerity rhetoric. They all rejected the necessity of austerity and sought to infuse collective political imagination with a common goal: the end of the era of austerity.

Strictly speaking, there was no single organisational structure that coordinated the activities of the anti-austerity campaign. Its form was more that of an assemblage of diverse constituencies, more or less loosely associated, and benefited from existing networks of collective action that varied from local grassroots movements to the transnational Global Justice Movement. The heterogenous anti-austerity movement in the UK was confronted with at least three major challenges that every agent of social and political change faces. First, to create and project a credible identity; second, to communicate effectively an argument that made a reasonable case against the imperative of austerity; third, to achieve an affective connection with the wider public in order to gain its support. Considering that these challenges emerged amidst a context in which deficit reduction was being presented as an absolute priority, the task of the campaign was nothing less but the creation of a new, alternative common sense to that of austerity.

Anti-austerity rhetoric took many forms, but one of the most powerful strategies its agents used was that of claiming the identity of the truth-teller. This strategy can raise the public profile of agents of political change by presenting them as credible and trustworthy, while it assists them to challenge the hegemonic order of truth. The latter was exemplified in occasions such as David Cameron’s ‘let me tell you a plain truth: there is no magic money tree’. Ultimately, the appeal to truth-telling helped to register in public consciousness the idea that there is an alternative way to respond to the crisis, a crisis that taxpayers should not pay for.

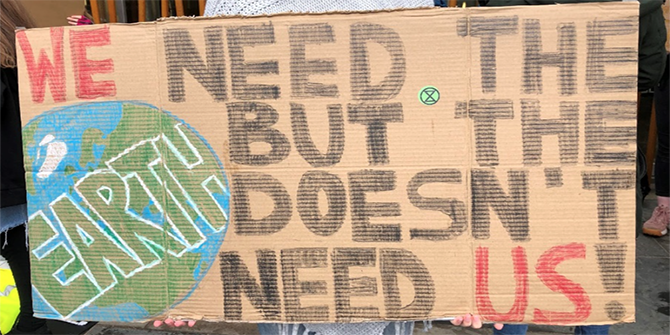

There are several instances on which agents of anti-austerity presented themselves as agents of truth or ‘exposers’ of lies: UK Uncut stated that its mission was to ʻexpose the cruelty and liesʼ of those who claimed that there was no alternative to austerity; anti-austerity demonstrators chanted Captain Skaʼs now iconic ʻLiar Liarʼ while holding pictures of agents of austerity; and Peopleʼs Manifesto argued that ʻBritish big business exports more capital abroad than it invests at homeʼ. Employing as their overarching argument the idea that there is an alternative to cuts, campaigners against austerity sought to rigidly separate themselves from the ʻlyingʼ government and its supporters, multi-millionaires, bankers, and ‘the elite’. Unlike David Cameron’s infamous soundbite, we were not in this all together.

If anything, the campaign against austerity in Britain created opportunities for political engagement, as well as for redefining where politics happens and who is its agent. It was a campaign that brought together contending voices that challenged the TINA logic of austerity and channeled political discontent, creating the possibility to demand alternative ways of understanding and responding to the crisis. Nonetheless, the fact that the rhetoric of the campaign was unavoidably focused around opposition rather than affirmation had a detrimental effect on the more constructive message that the campaign attempted to communicate. As a result, any attempt to put forward a positive social vision by appealing to social justice and equality was ultimately lost amidst the noise of discrediting chants and slogans.

________

Note: the above draws on the author’s chapter published in Judi Atkins and John Gaffney, eds. (2017) Voices of the UK Left: Rhetoric, Ideology and the Performance of Politics (Palgrave Macmillan).

Sophia Hatzisavvidou is a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at the University of Bath. She is researching environmental rhetoric and how it shapes public understanding of environmental issues.

Sophia Hatzisavvidou is a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at the University of Bath. She is researching environmental rhetoric and how it shapes public understanding of environmental issues.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image: Pixabay (public domain).

Up to the 2017 general election the Conservatives could always criticise Labour borrowing as a Bad Thing because “there is no magic money tree”.

Yet when the Conservatives needed £1 billion to give to the DUP to get their support for a minority government they went to the magic money tree. Even the Great British Public—who are not outstanding in their knowledge of macro economics—understood what was going on.

So that criticism of Labour borrowing can no longer be used; the public are onto it. A new criticism was needed, something that economically-naive people can understand.

The Conservatives seemed to have settled on: “what about the interest that Labour would have to pay on their borrowing?” Usefully, a lot of people understand that you have to pay interest on a loan. The good news for the Conservatives is that a lot of those same people think that you run the economy of a country just like that that of a household.

We see this time and again:For the mention of ‘anti-austerity’ [& anti-Brexit: anti-‘X’] uses many of the same lyrics while attempting to change the ‘tune’. All of which tends to reinforce the very argument that it means to counter.

Coupled with this there is an inbuilt atrophy in the original ‘austerity’ policy:It’s proponents can always say “its working”, “not much longer now” &c..

That The Fixed-Term Parliament Act was sold as the very tool to complete the job of bringing us back on course hardly rates a mention.

What a pity, that an absence of vision for any alternative has resulted now in an insistence that ‘Austerity’ be played out to the utter detriment to us all, in order to drive-home the message that ‘Political Actors’ have been unable to articulate to any effect.