In this post, Will Jennings and Gerry Stoker argue that voters supporting the two main anti-politics parties in the 2015 general election have policy preferences that are polar opposites. Because of this, they suggest that trying to be friends with both Ukip and Green supporters won’t work for the mainstream parties.

In this post, Will Jennings and Gerry Stoker argue that voters supporting the two main anti-politics parties in the 2015 general election have policy preferences that are polar opposites. Because of this, they suggest that trying to be friends with both Ukip and Green supporters won’t work for the mainstream parties.

There is a polarity at the heart of British politics that is triggered by anti-politics. Both Ukip and Green supporters share a deep sense of disillusionment with the political class and functioning of British democracy. In almost every other respect, though, their grievances with what is on offer from the political mainstream diverge – leading to polarities that require both Labour and the Conservatives to defend against an attack from both their left and right flanks.

The mainstream parties recognise the threat but are in much more of a bind when it comes to how to respond than they understand. First the political disenchantment at the heart of Ukip and Green support means that their voters have stopped listening to mainstream parties to some degree and second the polarity of Green and Ukip positions means that if mainstream parties try to appease one set of voters they run the risk of simply driving others away from them.

As part of our ongoing investigation into the causes and impacts of political disaffection, we have undertaken a systematic comparison of the determinants of Ukip and Green Party support, based on the British Election Study’s Continuous Monitoring Survey (2009-13) and Internet Panel Study (2014). Full details of our analyses can be found here (the Ukip analyses replicate earlier work reported here).

The results across both periods – which start well before the height of the Ukip and Green surges – are striking. Distrust of politicians is almost as big a factor for Greens as it is for Ukip supporters (it is interesting that this effect is slightly weaker for 2014 as the Greens have picked up more popular support). The odds of someone intending to vote Green or Ukip are up to two and a half times higher (and at a minimum 50% higher) if they express distrust in politicians. People who intend to vote for UKIP and the Greens are also more dissatisfied with British democracy, dislike both David Cameron and Ed Miliband, and more likely to agree that “politicians don’t care what people like me think”. Interestingly, Greens are more likely to accept the view that “it is difficult to understand government and politics”, whereas Ukippers disagree – for them politics is not as complicated as is made out. Even controlling for the demographic and attitudinal factors identified in the popular and widely accepted Ford and Goodwin thesis, political distrust and disaffection is a major driver of support for the Greens and UKIP.

The idea that Ukip or the Greens represent a threat is not news to the political parties. Labour’s big data election analyst Ian Warren long since identified the Greens as key to understanding the distinctive geography of the new British politics. And the Tories plainly see Ukip as a major concern. But the standard mainstream party response is to focus on policy red meat that both parties should throw Ukip supporters to win them back. Disaffection with politics means this strategy may not work because those voters are less trusting of politics and so less likely, anyway, to believe the policy crackdowns and inducements they are offered. But appeasing Ukip has in turn created space for the rise of the Greens – though it remains to be seen to what extent their gains in the polls translate into votes on Election Day.

Our old politics is struggling to cope with a new world of polar opposites. While they may be disaffected and share distrust in politics and politicians, the attitudes of Ukip and Green supporters differ in important ways. Ukip voters are more likely to be male, aged 55 and over, and read right-wing tabloids. Greens are more likely to be female, younger, and not tabloid readers. Ukippers want to leave the EU are worried about immigration, and tend to be of the view that “ordinary people do not get their fair share”. They also are more likely to think that equal opportunities for ethnic minorities and gays and lesbians have gone too far. Greens on the other hand are pro-EU, more likely to express positive attitudes on immigration, believe that government should be concerned about inequality, and disagree that “too many people rely on government handouts”. They also strongly disagree that environmental protection has gone too far. In contrast to Greens, Ukip supporters tend to be less supportive of redistribution or government intervention, but still care about ordinary people getting a fair deal. They may be hacked off about the economic status quo, but Ukip supporters are not necessarily natural bedfellows for Labour’s brand of redistributive social democracy.

These results show that the Left behind thesis that the demographic of Ukip supporters means they are natural Labour voters has perhaps been overplayed – the set of policy attitudes that they express would be just at home in the “new working class” identified by Ivor Crewe in Thatcher’s heyday. These people once may have voted for Labour and Tony Blair – in the guise of “Mondeo Man” – but their policy and cultural attitudes are distinctive and not social democratic in any way. By trying to placate voters’ concerns about immigration and the EU, parties may well have driven voters into the arms of the Greens – who are the polar opposite to Ukip supporters on crucial cultural and policy attitudes.

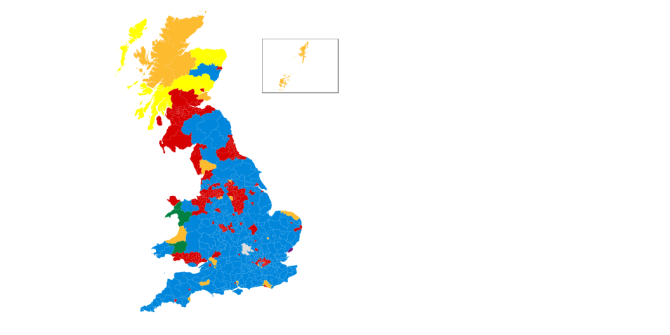

Further Greens and UKIP supporters are not “insurgents” in any normal sense of the word (they are unarmed as far as we know!). They have a clear set of ideological dispositions and policy preferences that are not being met by the political parties or within the political system as it currently stands. That those preferences are at polar opposites highlights the impossibility for both Labour and Conservatives of mollifying both sides. Their impact on rising support for the new forces in British politics simply highlights the lack of discussion about the underlying attitudinal cleavages that are giving rise to these disparate political movements and the extent to which they are reshaping the political map.

This research is funded under the ESRC research award ‘Popular Understandings of Politics in Britain, 1937-2014’ (Nick Clarke, Gerry Stoker, Will Jennings and Jonathan Moss). See further details here. This post was originally published on the New Statesman’s May2015 blog.

Will Jennings is Professor of Political Science and Public Policy and Director of the Centre for Citizenship, Globalisation and Governance at the University of Southampton

Will Jennings is Professor of Political Science and Public Policy and Director of the Centre for Citizenship, Globalisation and Governance at the University of Southampton

Gerry Stoker is Professor of Politics and Governance at the University of Southampton

Gerry Stoker is Professor of Politics and Governance at the University of Southampton