Scott James and Lucia Quaglia discuss the UK’s role in shaping post-crisis financial regulatory reform, and assess the implications of its withdrawal from the EU. Drawing on their recent book, they use a domestic political economy approach to examine how the interaction of UK officials, financial regulators, and the financial industry shaped UK preferences, strategy, and influence in international and EU-level regulatory negotiations. They conclude by reflecting on the future of UK financial regulation after Brexit.

Scott James and Lucia Quaglia discuss the UK’s role in shaping post-crisis financial regulatory reform, and assess the implications of its withdrawal from the EU. Drawing on their recent book, they use a domestic political economy approach to examine how the interaction of UK officials, financial regulators, and the financial industry shaped UK preferences, strategy, and influence in international and EU-level regulatory negotiations. They conclude by reflecting on the future of UK financial regulation after Brexit.

The crisis which engulfed the international financial system a decade ago came as a profound shock to the British political and regulatory establishment. In the years prior to the crash, the UK financial services sector—concentrated in the City of London—emerged as one of the world’s largest and most important international financial centres. The near collapse of the UK financial system after 2007 fundamentally challenged entrenched ideas about efficient financial markets and ‘light touch’ regulation. After a period of soul searching, policymakers vowed to place themselves at the forefront of regulatory reform efforts aimed at restoring financial stability and protecting taxpayers.

Our book sets out to understand the UK’s pivotal role and influence in shaping post-crisis financial regulation in a multi-level context. It addresses two main puzzles. The first relates to the fact that since the financial crisis, the UK has pursued increasingly stringent ‘market-shaping’ financial regulations in certain sectors (such as banking and derivatives), but not others (notably hedge funds). Moreover, regulators have played a leading role in promoting greater harmonization around tougher financial standards in some areas and at some levels (often at the international level), but have resisted similar efforts in other areas and at other levels (particularly in the EU). How do we explain this variation in regulatory outcomes? The second puzzle concerns the UK’s decision to withdraw from the EU. Why has the UK decided to leave the EU single market in services when this poses such a fundamental threat to the prosperity of the City of London? And how is Brexit likely to impact on the UK’s regulatory preferences and influence at the international level in the future?

We suggest that existing explanations rooted in comparative political economy, international political economy, and business power are not well equipped to account for the UK’s shifting regulatory outlook over the past decade. We also argue that they provide a poor guide to the actions of UK policymakers with regard to the Brexit negotiations and the future UK–EU relationship in financial services.

To address this, the book develops a domestic political economy approach, better suited to capturing the dynamics of contestation and competition between domestic groups in the development of financial regulation. The framework uses a two-step method to: 1) examine the interaction of three key domestic groups—elected officials, financial regulators, and the financial industry—in the process of regulatory preference formation; and 2) investigate how this domestic context shapes the strategies and influence of national policymakers in international and EU regulatory arenas.

At the domestic level, we consider how the need for financial regulators to balance competing pressures for financial stability (from elected officials) and international competitiveness (from industry), as well as regulatory concerns about managing cross-border externalities, often leads them to support the development of new international and EU rules. At the international and EU levels, we analyse how negotiators seek to leverage both domestic and external resources (including market power, regulatory capacity, domestic constraints, and alliance-building) to shape the outcome of multi-level regulatory negotiations.

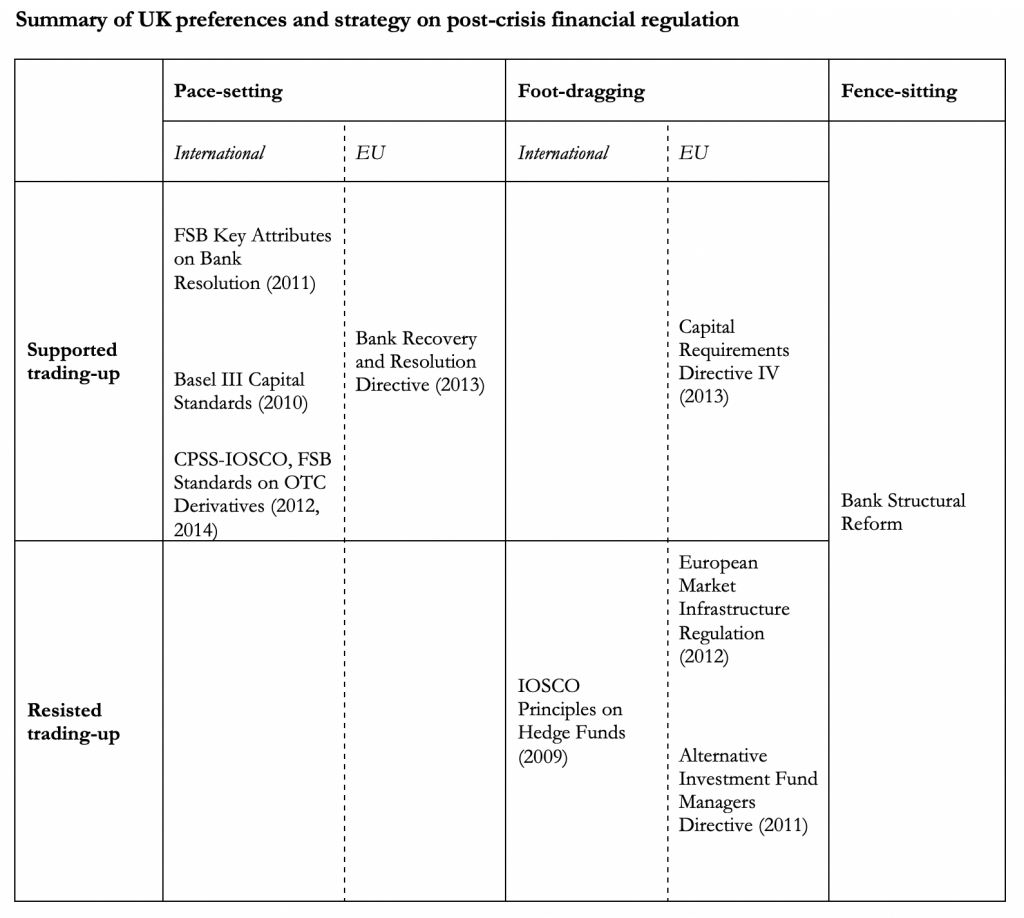

The framework is used to explain and assess the UK’s role in shaping post-crisis financial regulation across five key regulatory domains: 1) bank capital and liquidity requirements; 2) bank resolution rules; 3) rules on bank structure; 4) hedge-fund regulation; and 5) regulation of derivatives. For each case study we analyse three core aspects of the UK’s role: its regulatory preferences (whether it supported the adoption of more stringent rules, i.e. ‘trading up’, or not); regulatory strategy (whether UK negotiators are ‘pace-setters’, ‘foot-draggers’, or ‘fence-sitters’ in regulatory negotiations); and regulatory influence (the UK’s effectiveness in shaping regulatory outcomes).

The book makes three main claims:

Regulatory preferences. Political pressure from UK-elected officials for tougher regulation of bank capital and bank resolution, combined with strengthened domestic regulatory institutions, curtailed the influence of the financial industry and empowered UK regulators to pursue more stringent rules (i.e. trading up) with a view to safeguarding financial stability. In other areas, notably on bank structure and derivatives trading, UK regulators acted independently in the pursuit of tougher regulation, and had to actively build political support for their position at home. By contrast, in the case of hedge funds, the capacity of regulators to strengthen regulation was limited by a lack of political support and diminished institutional resources. Consequently, the hedge-fund industry was highly effective in defining the UK’s preferences in opposition to trading-up so as to defend the sector’s competitiveness.

Regulatory strategy. In the pursuit of more stringent rules, UK negotiators acted as pace-setters for international harmonization to minimize the impact on the UK’s competitiveness by creating a level playing field for industry (bank capital and liquidity); and to address the financial instability risks generated by cross-border externalities (bank resolution and derivatives). By contrast, they acted as foot-draggers at the EU level when harmonization threatened the light-touch regulation of hedge funds and London’s dominant position in derivative trading; but also when EU rules sought to dilute international standards on bank capital. In addition, UK negotiators adopted a fence-sitting strategy in the case of bank structural reform because unilateral action by the US, together with resistance to reform in France and Germany, ruled out the development of a harmonized approach.

Regulatory influence. UK regulators were more successful in shaping post-crisis standards at the international level because they were better placed to leverage their market power and regulatory capacity in technocratic fora; were able to exploit their prominent pre-crisis role in existing transnational regulatory networks; and forged important alliances with like-minded regulators (particularly the US). At the EU level, the UK was effective in shaping regulation when issues were less politicized (bank resolution and derivatives); but less influential as issues became more politicized (bank capital, hedge funds, and the clearing of euro-denominated derivatives) because it struggled to build alliances with other member states. Instead, UK negotiators used legal challenges and domestic constraints to block reform (e.g. euro clearing) or to secure a UK-specific exemption (bank capital and structural reform).

The final chapter considers the implications of Brexit for UK financial regulation. Analysed through the lens of our domestic political economy framework, we outline the likely future UK–EU relationship in financial services by analysing the preferences of elected officials, regulators, and industry; and assess how Brexit is likely to affect the UK’s role—its preferences, strategies and influence—in shaping financial regulation in the future.

We make two main arguments. With respect to the UK’s preferences, we argue that the political context was pivotal to shaping the ‘hard’ Brexit position set out by elected officials following the 2016 referendum. This was bolstered by financial regulators fearful of being reduced to the role of ‘rule-takers’ from Brussels, and a financial industry that lacked influence due to internal industry divisions and institutional barriers to access. Ultimately, however, the UK’s weak negotiating position forced the government to settle for a looser future relationship, based on the EU’s rules governing regulatory ‘equivalence’ for third countries. At the EU level, national governments and the EU institutions were steadfast in refusing to countenance a special deal for the City of London. This did not simply reflect the importance of defending the integrity of the EU single market, but also a desire by some member states—particularly France and Germany—to exploit Brexit to boost their domestic financial centres. Moreover, we suggest that this commercial self-interest stymied efforts by the EU27 financial industry to mobilize a transnational coalition around Brexit.

Looking to the future, we conclude that the post-Brexit UK–EU relationship will most likely be based on the EU’s existing third-country regime. UK-elected officials, regulators, and industry are likely to seek to compensate for the loss of influence in Europe by mobilizing greater resources and strengthening alliances at the international level. Yet, the future direction of UK financial regulation remains highly unpredictable: subject to both centripetal and centrifugal political forces, the outcome of which will be determined by struggles for power at home and in Brussels over the coming years.

_______________________

The UK and Multi-Level Financial Regulation: From Post-crisis Reform to Brexit was published by Oxford University Press in 2020.

Scott James (@DrScottJames) is Reader in Political Economy at King’s College London.

Scott James (@DrScottJames) is Reader in Political Economy at King’s College London.

Lucia Quaglia is Professor of Political Science at the University of Bologna.

Lucia Quaglia is Professor of Political Science at the University of Bologna.

Photo by Ed Robertson on Unsplash.