This week the Church of England published a letter from the House of Bishops to the people and parishes for the general election. In this post, Steve Fisher examines how the political preferences of Church of England members have changed since 2010. He shows that UKIP are performing particularly well amongst voters who identify themselves as members of the Church of England. One conclusion he draws is that the political preferences of the bishops may not match that of the regular members of the Church.

This week the Church of England published a letter from the House of Bishops to the people and parishes for the general election. In this post, Steve Fisher examines how the political preferences of Church of England members have changed since 2010. He shows that UKIP are performing particularly well amongst voters who identify themselves as members of the Church of England. One conclusion he draws is that the political preferences of the bishops may not match that of the regular members of the Church.

The House of Bishops’ letter is explicitly not advice on whom to vote for or a policy wish list but a call for a “new direction” for our “political life”. It emphasises values of community and neighbourliness, proclaims a need for parties to offer a “fresh moral vision” and for everyone to engage positively in the political process. While some have claimed that the letter attacks the current government and is left wing, the church denies this reading (e.g. see here and here).

One way to consider the partisan implications of the church’s teaching is to look at the attitudes and behaviour of its members. It is too soon for a proper assessment of the impact of the publication of the letter. But it is reasonable to consider whether and how the political preferences of church members have evolved since the last election. After all, the church argues that the bishops’ views on how voters should approach the election are rooted in Christian faith and deeper traditions of all the main political parties. So they have presumably long been reflected in church teaching. Moreover, the letter repeats points made in previous interventions by the church in political debate since 2010 (e.g. see here).

What then do changes in vote intention since 2010 suggest about the church’s success at instilling the values of its bishops among those who consider themselves members?

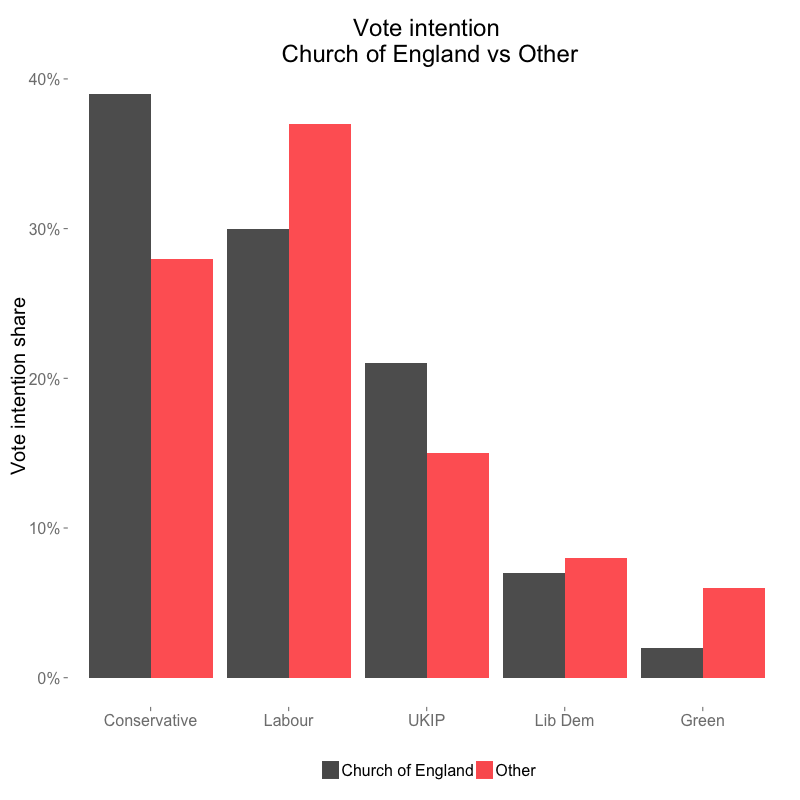

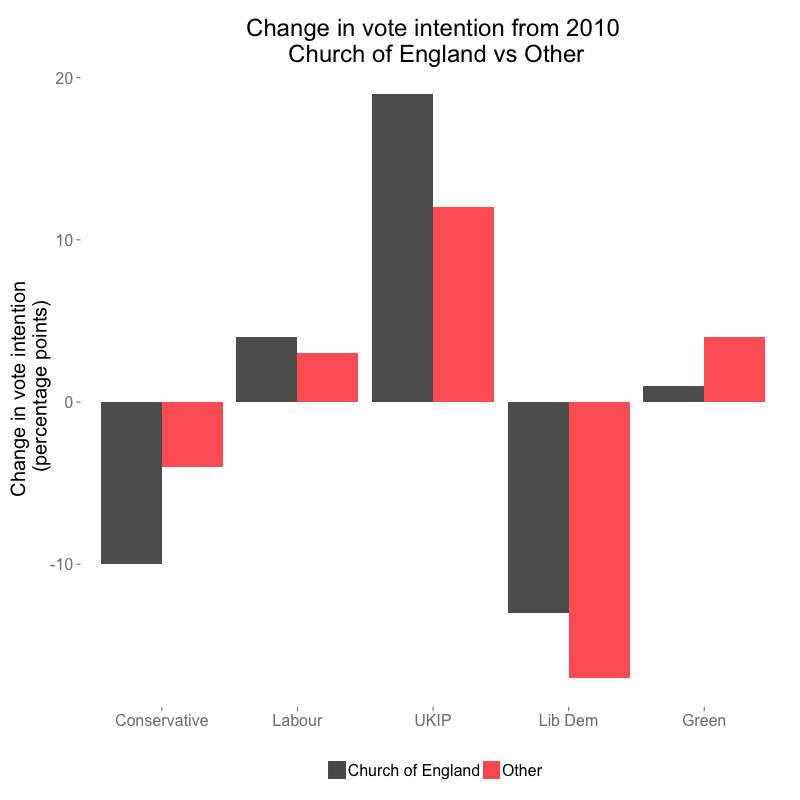

The graphs below show current vote intention and change since 2010. All figures are percentage points. The shares show that the 28% of respondents who consider themselves to be a member of the Church of England are much more likely to vote Conservative and less likely to vote Labour than other voters. This fits with the long-standing stable pattern of religious voting, and classic notions of the Church of England as the Tory party at prayer.

What is new is the weakening of the Tory advantage among Church of England identifiers and correspondingly greater rise of UKIP. The final column in the table shows is that the drop in the Conservative vote since 2010 is somewhat greater among C of E identifiers than it is among others. This essentially because the rate of switching from Tory to UKIP has been higher among C of E identifiers than it is among other voters. So now these data tell us that UKIP are doing some 6 points better among those who think of themselves as members of the Church of England.

As Robert Ford and Matthew Goodwin have pointed out, UKIP have been most successful in attracting votes from those who are older, white, working class, male and have relatively little formal education. But even after controlling for all these factors and previous vote (including none), those who identify as C of E are more likely to say they will vote UKIP. The same is not true of other Christian denominations and members of other religions.

There is no identifiable ‘effect’ of being Anglican after also accounting for attitudes to immigration, which are very strong predictors of UKIP voting. Of those who consider themselves members of the Church of England 35% said they thought that immigration undermines cultural life in Britain, compared with just 22% of other voters.

It is not just immigration that accounts for the high rate of UKIP voting among Church of England identifiers. In a statistical sense the C of E effect can be also accounted for by attitudes on equality for gays and lesbians, perhaps because of the gay marriage legislation. More generally a libertarian-authoritarian values scale also seems to ‘explain’ the C of E effect. Those who identify with the Church of England are more to have authoritarian attitudes of a variety of issues, including immigration, and these make them more likely to vote UKIP.

These findings are in marked contrast with the pastoral letter which cautions against stirring up resentment against immigrants and various other groups (paragraph 76). While acknowledging that it is not always racist to question immigration (paragraph 104) the letter also says “The politics of migration has, too often, been framed in crude terms of “us” and “them” with scant regard for the Christian traditions of neighbourliness and hospitality. The way we talk about migration, with ethnically identifiable communities being treated as “the problem” has, deliberately or inadvertently, created an ugly undercurrent of racism in every debate about immigration.” (para 103). Arguably then the views of the bishops on immigration do not sit well with the attitudes and voting intentions of many of those who consider themselves members of the church.

The pastoral letter makes no mention of homosexuality, but it does talk about some other issues that are related to UKIP voting. On pages 29-30 the letter promotes international cooperation within Europe, but Anglican identifiers are much more likely (38% to 25%) to say that Britain should do all it can to protect its independence from the European Union. However, Euroscepticism (along with economic pessimism and anti-environmentalism) does not help explain why Church of England identifiers are more likely to support UKIP.

To be fair to the bishops it is well known that many who consider themselves members of the church do not attend much (if at all), and the attitudes of frequent attenders are typically more liberal than those who identify but do not attend much or at all. The BES data do not currently allow us to examine the implications of this, but previous research suggests it is likely to be the least religious of the C of E identifiers who would be most likely to vote UKIP.

Even if the pastoral letter does not reflect well the politics of those who consider themselves members of the Church of England, it will appeal to plenty of those who say they have no religion. Perhaps the letter will change attitudes about the church among those outside it more than it will change attitudes about politics of those inside the church.

Note: Thanks to Jon Mellon for help with the BES data and to Zac Ward-Perkins for the final point.

Steve Fisher is an Associate Professor in Political Sociology and the Fellow and Tutor in Politics at Trinity College, University of Oxford. He is also one half of the team at electionsetc.com.

1 Comments