The economy features prominently in the public debate, even though the jargon and decision-making behind it is completely inaccessible to much of the public. As a result, and to articulate their economic grievances, many use the language of nationalism and immigration – something that was particularly evident in the Brexit debate. The way we use economics must therefore be made more democratic and open, explain Cahal Moran, Zach Ward-Perkins, and Joe Earle.

The economy features prominently in the public debate, even though the jargon and decision-making behind it is completely inaccessible to much of the public. As a result, and to articulate their economic grievances, many use the language of nationalism and immigration – something that was particularly evident in the Brexit debate. The way we use economics must therefore be made more democratic and open, explain Cahal Moran, Zach Ward-Perkins, and Joe Earle.

Michael Gove’s infamous claim that the nation has “had enough of experts” has provoked both outrage and soul-searching among experts. But now that the dust is settling on the Brexit vote, what is the future for experts in what many call an era of ‘post-truth’ politics?

Experts are essential in the modern world but arguably, in the case of economics, they have overreached themselves, undermining democracy and fueling popular discontent in the process. It is this popular discontent that Gove and the Leave campaign exploited. Without understanding the root causes of this discontent, experts cannot hope to rebut it; therefore it’s necessary to consider how wider historical trajectories have shaped the political and economic systems that formed the backdrop to the referendum debate.

Econocracy

The political system we have at present is what we’ve termed an ‘econocracy’: a society in which political goals are defined in terms of their effect on the economy; and the economy itself is believed to be a distinct system with its own logic that requires experts to manage it. An econocracy has all the formal institutions of a representative democracy, but public economic discussion is conducted in a language few understand, while economic policy-making is viewed as a technical rather than a political process. Since economics has a direct effect on peoples’ lives, this leads to a disconnect between those versed in the language and the majority of citizens who are not.

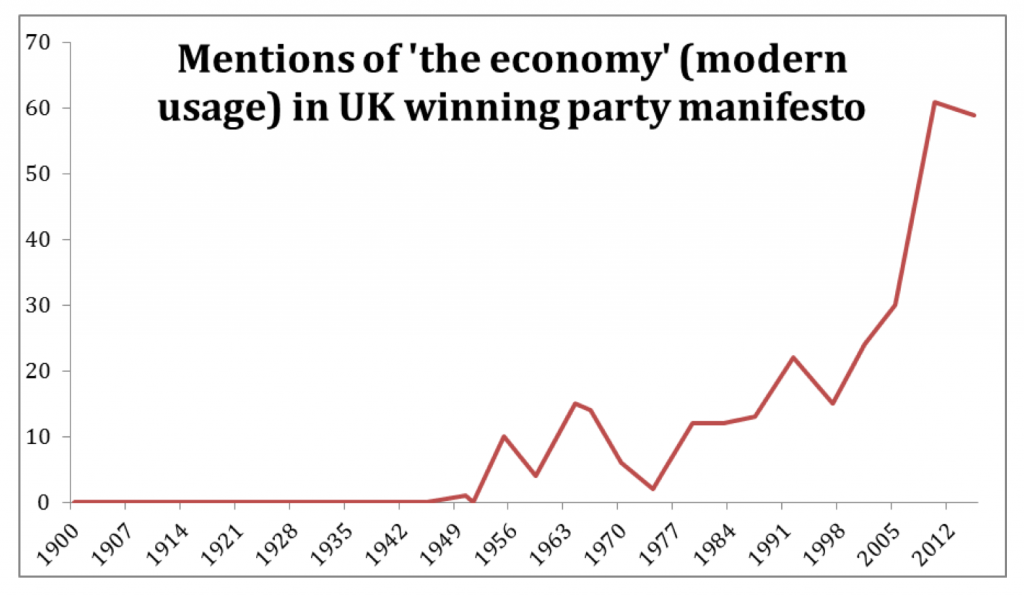

The foundations of econocracy lie in the increasing importance of the idea of the economy in public life over the 20th century. As the figure below shows, the idea of the economy in its modern use only began to appear in party manifestos in the 1950s.

The first macroeconomic models of ‘the economy’ were created in the 1930s and the Treasury began preparing qualitative assessments of the country’s economic prospects shortly after the Second World War. By 1961, these projections had become quantitative and by the end of the 1970s it was predicted that there were 99 organisations producing forecasts of the economy.

Over four decades on and GDP growth is now one of the central indicators of success for governments, and it is unheard of for a party to win a general election without being viewed as competent on the economy. Econocracy is characterised not just by GDP but by a more general technocratic approach to public economic discussion and policymaking. Central Banks are the prime example of this tendency to move economic decision-making away from politics, but it is a trend that can be seen across the board. The Government Economic Service has tripled in size to 1600 employees since 2000 [based on an interview with a recently retired GES figure] and bodies ranging from the Competition Commission, utilities regulators and the Behavioural Insights Team all make political decisions based on economic expertise (largely without any public oversight).

Beyond that there are a number of international organisations including the International Monetary Fund, World Trade Organisation, World Bank and Bank for International Settlements which provide an international economic framework which measure and rank national economies, support economic development, act as lender of last resort and manage the global financial system.

Minding our language

In a YouGov poll, we asked 1,696 respondents their view on how politicians and the media talk about economics: only 12 per cent said it was done in an accessible way. This finding resonates with polling we did for our book: although 35 per cent of respondents felt happy engaging with economics, 47 per cent stated that they only talk about economics once a month or less. A further 12 per cent only talk about it 2 or 3 times a month.

Disengagement was considerably more prevalent among women and people from less privileged socio-economic backgrounds. Some of the popular reasons given for disengagement included ‘I have no interest in economics’, ‘I find economics difficult to understand’, and ‘economics is out of my hands so there is no point discussing it’. This is the process by which econocracy undermines and hollows out democracy.

It is in this context that the EU referendum took place. All the big economic institutions including the Treasury, IMF, OECD and the IFS carried out quantitative modelling to forecast the effects of Brexit on the economy. Academic economists were similar in their almost unanimous agreement that Brexit would be bad for the economy. Based on the historical record, we can see why many Remainers thought that this would be enough to win the argument.

But for a long time, and particularly visibly since 2008, a backlash against econocracy has been forming. Populist politicians from Trump to Varoufakis have, in different ways, defined themselves in opposition to technocratic government. This is why the Leave campaign explicitly sought to devalue the economic expertise much of the Remain case rested upon. Michael Gove compared experts supporting Remain to scientists who worked for the Nazis, and economic forecasts of Brexit were labelled as ‘Project Fear’. This strategy is effective in an econocracy because it plays on the fact that people feel disconnected from economic discussion and decision-making.

It has been widely recognised that economic insecurities were an underlying factor in the success of the Leave campaign. After all, social class and location were key determinants of how one voted, with Leave voters much more likely to have lower income and come from poorer areas.

But the language of nationalism and immigration filled the vacuum in the absence of a public language and spaces in which people could air their economic grievances. Nationalist and anti-immigration arguments clearly had more resonance with peoples’ lived experience of ‘the economy’ than abstract economic forecasts. Unless economists and politicians find a way to give people a feeling of ownership over economics and the tools to engage in economic debate, we risk economics becoming completely disregarded as irrelevant or propaganda. This outcome is a sure way to being locked into post-truth politics.

So far though the foundations of the econocracy have held strong. Retrospective analysis is framing the vote to leave as a contest between identity and emotions on one side and economics on the other. But this rests on two assumptions which are at the heart of econocracy and prevent any significant democratisation of economics. Firstly, by framing economics in opposition to identity and emotion it implies that economics is technical and scientific but not political; as long as it is viewed as such there is little reason to involve the public in economic discussion.

Secondly, by implying that those who voted leave did so based on emotion and identity, it denies the possibility that Leave voters did so based on different economic logic or arguments. In short it represents the idea that if Leave voters had based their decision on economics they would have come to the same conclusion experts did which. This belief precludes the possibility of legitimate political debate about economic issues and reinforces econocracy.

From here, the academic discipline of economics and our economic institutions have two choices. Either they frame Leave voters as emotional and irrational and thus carry on with the status quo of econocracy: continuing to lock people out of economic discussion. Or they can take seriously the ways in which econocracy undermines democracy and fails to give people a voice to express their economic grievances. By moving from detached authority figures to humble advisors, economists could regain the trust of the public and stop the scary drift towards a world of post-truth politics.

Of course, experts can only be as good as their knowledge. The latter path requires significant reform within the discipline of economics. Economics must recognise that the study of the economy is inherently bound up with politics, values and emotions because it is the study of humans. It must also recognise the limitations of its knowledge in a complex world, and take seriously the contribution that citizens can make by contributing dispersed knowledge through more participatory political processes. Currently, the discipline of economics as a body of knowledge doesn’t incorporate these insights which means that experts are more likely to feel that the status quo is the right way to do economics.

In our book we set out a vision of a public interest economics linked to reforming the discipline. The EU Referendum has opened up major fault lines and one of those is between those who feel they own economics and those who know it isn’t supposed to be for them. Our answer to those who are saying that the vote for Brexit showed that we shouldn’t let people make these decisions is that we need more democracy, not less.

____

Note: the above draws on the authors’ forthcoming book “The Econocracy: the perils of leaving economics to the experts” (forthcoming October/November 2016). The authors are members of Rethinking Economics, an international student led movement seeking to reform the discipline of economics so that it is more pluralist, critical, democratic and participatory.

Cahal Moran is studying for a PhD in economics at the University of Manchester. His research is in applied behavioural economics. He is the current chair of the Post-Crash Economics Society at the University of Manchester and was the co-author of the Post-Crash Economics Society Report Economics, Education and Unlearning (2014).

Cahal Moran is studying for a PhD in economics at the University of Manchester. His research is in applied behavioural economics. He is the current chair of the Post-Crash Economics Society at the University of Manchester and was the co-author of the Post-Crash Economics Society Report Economics, Education and Unlearning (2014). Zach Ward-Perkins is a trustee of Rethinking Economics and a founding member of the Post-Crash Economics Society in Manchester. He has written extensively on economics education, elections and polling for the Guardian, the Royal Economic Society and on the blogosphere.

Zach Ward-Perkins is a trustee of Rethinking Economics and a founding member of the Post-Crash Economics Society in Manchester. He has written extensively on economics education, elections and polling for the Guardian, the Royal Economic Society and on the blogosphere. Joe Earle is a freelance action researcher and organiser currently working on a project looking at the possibilities for social innovation in adult social care. He is also a trustee of Economy (www.ecnmy.org) which seeks to catalyse and facilitate a public conversation about the economy and in doing so democratise economics.

Joe Earle is a freelance action researcher and organiser currently working on a project looking at the possibilities for social innovation in adult social care. He is also a trustee of Economy (www.ecnmy.org) which seeks to catalyse and facilitate a public conversation about the economy and in doing so democratise economics.

Having followed Richard D Wolff for years, Mark Blyth for months, having followed Yanis Varuofakis, listened to the odd interview with John Ralston I have concluded the following:

For the most part Economics (and even more so Neo Liberal Economics) is not a science or even an academic discipline. It is an ideology.

Just seen this and immediately pre-ordered the book. The argument that economics has overtaken the debate is almost complete. Now we have even DfID in the UK tying up and aid to how it would benefit the UK’s economy and the dangers in this are clear (to some, anyway). There used to be ‘political economics’ that attempted to tie the subject of economics (as you write, a people subject – when I was at Manchester University it was taught alongside Sociology and Anthropology) within a political context.

Economics has been buried beneath numbers in a way that tempts everyone to believe that it is akin to physics. It is far from it. I wish this book well as I wish the work being done at Manchester in Post-Crash Economics. I would add that in a world of “Natural Capital” (where ‘we’ are attempting to develop numbers by which to ‘value’ trees and rivers so that economists and business people can better understand costs) the challenge is a great one and economists and accountants (I have a degree in economics and am a qualified accountant – so have been severely infected) are not easy to shift from the quantitative mindset that has engulfed them, where the qualitative seems too hard to understand and where the use of computers and larger algorithms provide a sense of accuracy when just one error in assumptions usually undoes a mass of calculations.

I suspect you might enjoy this one too Jeff 🙂 http://www.chelseagreen.com/surviving-the-future

This is great – I’ve just pre-ordered my copy and can’t wait to see it!

It ties in beautifully with my late mentor’s book – Surviving the Future – which is launching next month on similar themes, all about the rediscovery of active citizenship. As my editor’s preface states:

“Society’s answers to the questions of economics shape the bulk of our waking hours, and so Surviving the Future returns them to their rightful owners. In the process, it reminds us of how extreme and unusual today’s ‘ordinary’ is, and shows zero tolerance for those who benefit from presenting these life-defining questions as impenetrable, none-of-our-business and, of all things, boring.”

Dr. Chris Shaw is reading it for the LSE Review of Books, and I’ll be glad to send the authors of this piece a copy if they drop me a line. Full details at http://www.chelseagreen.com/surviving-the-future

All power to you. May both books find a wide readership, and help us all to reclaim our control over the direction of our lives.

Post Brexit, I’ve been thinking along the lines of values and rightly or wrongly have come to the conclusion that Brexit values align with a more communitarian outlook whereas Bremain values align with a more liberal outlook. This points to the dynamic between communitarianism and liberalism with the former evoking a need for community continuity and stability underlied by democracy and resilience and the latter evoking a need for community change and growth underlied by technocracy and wealth.

However, the trouble with liberalism and its inherent need for change and growth is that it is ecologically and socially deconstructive which is a good thing if change and growth is required but also a bad thing since it is inherently unsustainable. Liberalism, whether social or economic, is fundamentally unsustainable because if all living things had the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness then we would all starve or else be immobilised by moral constraint. This belies the fact that the sustainability of life is underpinned by life/death relationships but if not properly managed, these life/death relationships will inherently lead to unmanaged competition even if under the liberal framework of individual rights-based entitlements. In effect then, liberalism facilitates accumulation with few restrictions other than be nice to one another. This is why economic liberalism inherently leads to the formation of monopolies of power and consumerism and why social liberalism hollows out communities and leads to atomisation, loneliness and identity politics.

In this respect liberalism as a social policy tool has been a good thing in terms of deconstructing traditional communities based on entrenched patterns of patriarchy, gender inequality and class inequality but this creative destruction and has been a good thing in terms of improving standards of living now needs to be rolled back in order to allow communities to recoalesce around virtue-based value systems and in particular, ones I argue that are designed to create a sustainable future and so built on a platform of community democracy and community resilience.

This I think is the true nature of the Brexit backlash against the eu and the globalised liberalism that it supports. Unmanaged liberalism is inherently unsustainable and destructive and whilst it is a useful ideology to deconstruct and reform communities as a social change tool, at some point it is necessary to withdraw the use of this tool in order to allow communities to reformulate around different principles. It is therefore with irony that with regards the eu debate, the communitarians (brexiters) were using liberalism (democracy and the right to self-determination including border controls) to support their communitarian arguments whilst liberals (bremainers) were using communitarianism (cooperation and eu safeguards) to support their liberal arguments.

This highlights that liberalism functions as dynamic with communitarianism with the former being used to evoke change and growth through competition wheras the latter is used to evoke continuity and stability through cooperation. As such, yes the competition of liberalism is as important as the cooperation of communitarianism but each needs to be recognised for the benefits and losses they bring in order to manage social change and social continuity. In this respect, progress for its own sake and the constant social change and growth that liberalism brings through self-interested competition is damaging and unsustainable if it is not democratically consented to by all segments of society. In effect, by trying to bring half of a society unwillingly into the liberal mold whether through eu membership or through centralised government imposition that in effect manages eu policy is not only undemocratic but also exclusive of others that might wish for continuity and stability in order to build up decentralised democracy and resilience.

Liberalism does not allow for this regrounding of community values because it relies upon competition or creative destruction in order to constantly change and grow society or in international order terms, liberalism does not allow community cohesion because it requires communities to cooperate in order to compete in order to evoke change and growth on a global level.

In conclusion, without recognising that liberalism (individual liberty) forms an antogonistic relationship with communitarianism (social cohesion) and that the two need to be mediated according to democratic consensus then we are not only damaging our ecological and social relations through imposed competition (which arises because liberalism is unable to reconcile the rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness when expanded to all living life-forms) but we are also damaging our relation with our self since when this competitive outlook is internalised,it begins to form a divided and antagonistic self which goes some way to explain the bigoted behaviour from both sides of the eu debate.

So whilst liberalism is an important socio-economic policy tool to evoke change and growth through the application of negative rights, the inherently competitive and unsustainable effects of liberalism need to be recognised as such and so in turn, it needs to be recognised that liberalism has as its complimentary opposite a communitarian perspective that evokes continuity and stability through the application of positive rights which allows diverse communities to cooperate on a platform of responsibility and resilience which is mediated by democracy in order that diverse communities can formulate their own identities and values. However, if over time this continuity and stability creates entrenched inequalities, then liberalism again becomes useful to creatively deconstruct these entrenched inequalities. As such liberalism and its inherently competitve outcomes and communitarianism with its inherently cooperative outcomes are social policy tools which can be applied to varying degrees to create a managed dynamic between change and continuity. So, if continuity (and sustainability) is required then communitarianism needs to come to the fore whereas if change (and unsustainability) is required then liberalism needs to come to the fore. At present I would argue that communitatrianism needs to come to the fore in order to ingrain communities with a sustainable development ethic based on stability which I argue would be best achieved by creating a global cooperative network of decentralised democratic communities which is underpinned by an ethos of decentralised community resilience.

Is “econocracy” much more than a realisation that human well-being is more likely to be experienced in shared prosperity rather than the equal or unequal results of dearth? Most people do not talk about any science much. But because, say, toxicology is abstruse does not mean that the experts in it should not have a valued place in policy formulation. Getting it wrong can be calamitous. So can getting economic policy wrong. I suspect people in Zimbabwe or North Korea could have better lives had their rulers given more reliance to standard economics.

But the dismal science is not the same as toxicology where in vitro experiments can display the veracity of theories or otherwise. And the heated disputes between economists are evidence of that. But to the limited extent that it is predictive it is a vital component of policy making. But as in all policy formulation there is a crucial element of communication. More of the “pound in your pocket ” than endogenous growth. So humility, the acceptance of predictive limitations, and better communication not the rejection or diminution of true expertise.

Although the overall push for inclusion in your article is constructive, you appear to be saying that economics needs to be more accessible to the masses. I don’t think this is realistic as you cannot make politics, history, physics or any other discipline significantly more accessible by reframing the language. The masses lose trust in ‘experts’ when they fail to demonstrate humility, that is, they no longer welcome challenge in the light of new evidence. Historians continuously re-analyse periods of history over time, physicists are willing to radically change their view of how the universe works (as happened with Einsteins work), Mathematicians welcome close inspection of the theorems they arrive at by their peers and so on. The economic community doesn’t quite exhibit the same corrective tendencies, potentially because the discipline gets leaned on by vested interests. Inequality in the developed world has reached pre World War I levels and metrics around GDP, inflation, employment levels count for nothing when you have growing cross-sections of society with little or no access to the spoils and lagging behind in terms of wealth and income.

Do people trust themselves enough to evaluate new ideas in economics? For several I have been hawking an idea for a revolutionary monetary system and people have not even been willing to consider it, much less embrace it, much less advocate for it. They invariably come up with some dumb excuse to allow themselves to ignore it, like “It’s too simple.” On the face of it, there is nothing complicated about

E = MC(C) (no superscript available).

This monetary system would eliminate (involuntary) unemployment and poverty (at no cost to anyone, without having to redistribute anything) as well as using taxes–or debt–to fund government. (Government would be funded forever at the current per capita rate of total government spending as part of the operation of the monetary system.)

By the way, how many people have asked themselves first of all what my ‘qualifications’ are? I do have an M.A. in economics.