As the excavation of what explains the Brexit vote drills ever deeper, it is striking that the outcome of a campaign in which immigration was key appears to have come as a surprise, writes Hilary Pilkington. Based on insights from her ethnographic study of English Defence League activism, she explains why social researchers need to start studying views they might be uncomfortable with, but which are politically important to hear.

As the excavation of what explains the Brexit vote drills ever deeper, it is striking that the outcome of a campaign in which immigration was key appears to have come as a surprise, writes Hilary Pilkington. Based on insights from her ethnographic study of English Defence League activism, she explains why social researchers need to start studying views they might be uncomfortable with, but which are politically important to hear.

The UK has felt itself comfortably immune from political challenges from the far right. No far right party has succeeded in having a representative elected to national parliament, and electoral support for populist radical right parties has remained lower than in other western European states. The reasons for this are complex but might be attributed to a combination of: a relatively weak fascist political heritage; the first past the post electoral system; and the failure of the British National Party (BNP) to move in the direction of a ‘renewed’ radical right.

But this immunity is far from absolute. The European Value Survey (EVS, 1999-2000 and 2008-09 rounds) found base levels of xenophobia in the UK to hover around 20 per cent, which is typical of western European countries. On the single measure of anti-immigrant prejudice (EVS, 1999-2000), the level in the UK is actually higher (15.9 per cent) than the mean for western European countries (10.7 per cent). Since hostility to immigration is the most powerful predictor of support for populist extremist parties, the same potential base of support for the populist radical right and far right exists in the UK as elsewhere in Europe.

Advance warning of this was evident when the BNP gained two seats in the European parliamentary elections in 2009 and UKIP won the highest proportion of the national vote (27 per cent) in the subsequent elections in 2014. So why was it a surprise that on 23 June 2016, following a referendum campaign in which immigration was a key issue, 52 per cent of voters opted to leave the European Union?

I am not suggesting that those who voted to leave the EU are ‘far right’ – those wanting to leave span the political spectrum. Rather I see the surprise elicited by the referendum vote as symptomatic of a political complacency in how we understand and engage with what we conveniently think of as a pathological fringe. The tendency to label uncomfortable and contentious views as ‘far-right’ and treat them with disdain led to a failure to recognise how extant anxieties have become infused with increasingly mainstream frustration with the contemporary practice of politics. In this sense, the referendum provided a one-off opportunity to ‘be heard’.

Three years of ethnographic study of the EDL afforded the opportunity to understand the meanings grassroots activists attached to their activism. It allowed a nuanced exploration of the substance and form of expression of deeply uncomfortable views and how to understand them in relation to wider nationalist, racist, Islamophobic, and so-called white working class grievance discourses. But it also revealed a complex and often conflicted picture of the EDL that the stereotypical ‘drunken racist football hooligans’ image conceals.

While the movement clearly has a far right element – its own internal demons that a series of leaders have failed to banish – the EDL is representative of a new challenge to UK politics. It exemplifies the way in which, as Cas Mudde has argued, populist radical right attitudes constitute a radical variant of views found in wider society rather than ‘a normal pathology’ unconnected to the mainstream.

‘Not far right, but not far wrong’: EDL demonstration, Rotherham, September 2014 (Author provided)

‘Not far right, but not far wrong’: EDL demonstration, Rotherham, September 2014 (Author provided)

Nowhere is this clearer than in relation to attitudes towards, and experiences of, the formal political realm. Grassroots EDL activists demonstrate a profound disillusionment with the party political system, which is increasingly common among the general population as well. For most, participation in EDL actions was their first real political or civic engagement and they undertook that activism whilst continuing to distance themselves from the political by claiming ‘Politics are bollocks’, ‘I don’t know nothing about politics.’ or ‘I don’t follow politics’. For them, formal politics is duplicitous chatter. In contrast, activism in the EDL is ‘telling it as it is’ expressed in a ‘non-politics’ of action.

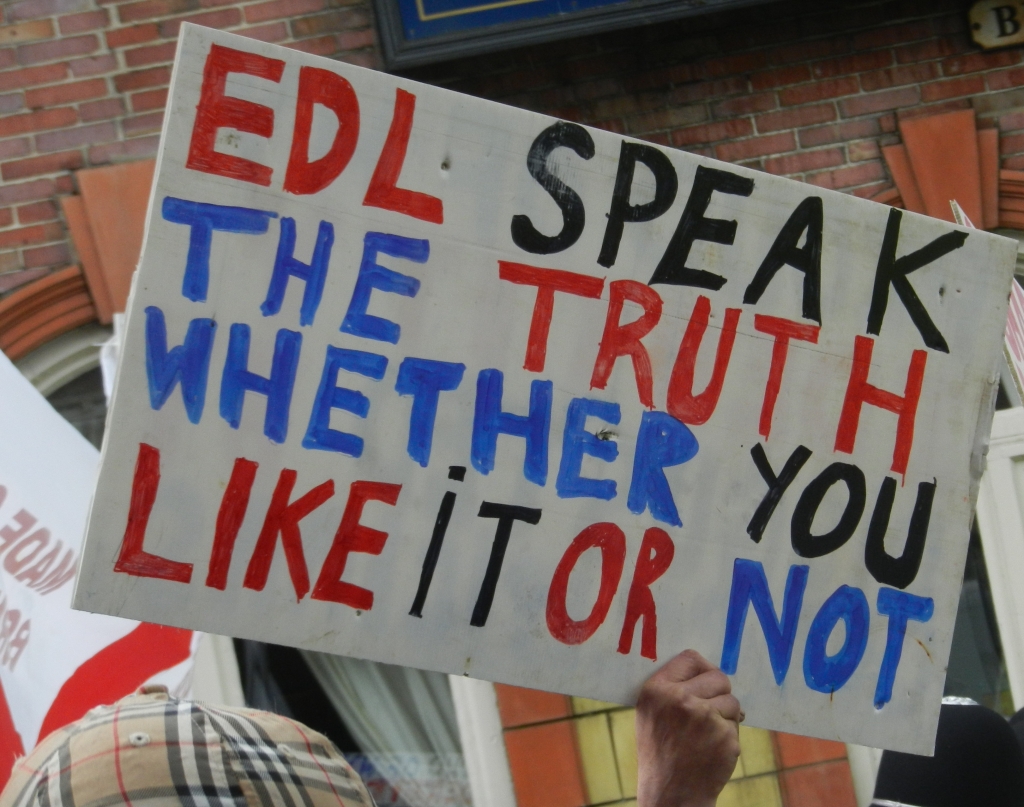

‘EDL speak the truth…’, EDL demonstration, Rotherham, May 2014 (Author provided)

‘EDL speak the truth…’, EDL demonstration, Rotherham, May 2014 (Author provided)

Attempts by white working-class communities to articulate their worsening position, Michael Kenny argues, have been ignored or dismissed as the product of ethnically charged nationalism or narrow-minded prejudice. EDL activists are acutely sensitive to this. They experience the political realm as governed by a politics of silencing in which the expression of their views, as well as government policy, are constrained by the application of the ‘racism label’. It is a system, they feel, kept in place through the legal and cultural circumscription of ‘acceptable’ issues for discussion. They perceive the political system as being set up not for dialogue with people but for their compliant listening. Bitter experience has taught them that it is best to keep ‘your head down’ and ‘your mouth shut’. But they choose to respond with a defiant insistence that ‘That ain’t EDL. EDL’s loud. […] Loud and proud’. EDL activism is a means of ‘getting your point across’ and ‘being heard’ epitomised in the slogan ‘Not racist, not violent, just no longer silent’.

EDL activists are highly sceptical that piercing the silence will make a difference. Few thought the demonstrations they participated in were an effective form of activism. But they were symbolically important. They showed the government ‘there are still people out there that don’t agree with them’.

While this mode of response may be exclusive to EDL activists, the feeling of being silenced is not. The larger FP7 MYPLACE project, of which this study of the EDL is a part, found that young people in the UK felt issues such as immigration were excluded from mainstream political discourse. Interviewed for the project in autumn 2012 (before the referendum had become a Conservative Party election pledge), one young woman expressed her concern that ‘the political parties are so intent on staying in the EU that they don’t want to discuss anything else that risks us being booted out or having to possibly leave’.

Residents in the white working-class community in Manchester studied by Lone and Silver around the same time as the MYPLACE research was conducted also felt that they were not able to talk freely about immigration and, if they did so, they risked being seen as ‘a racist’.

The English Defence League is one of those ‘distasteful’ groups that social researchers choose not to study, especially not ‘close up’. I say ‘choose’ not to study because rare cases of ethnographic study of far right and populist radical right movements show researchers can achieve the quality of relationships necessary to secure understanding of research subjects, despite a lack of shared political views or wider values.

We choose not to study them in this way not least because we fear that, explicitly or implicitly, we may become a legitimising mouthpiece for the organisation or cause. While concerns about this are understandable – and the researcher cannot control how their research is used subsequently – they should not be allowed to constrain social research. Erecting what Chantal Mouffe calls a cordon sanitaire around movements like the EDL and dismissing them as ‘far right’ might feel, on the surface, politically charged – but in practice it may be politically complacent. It promises to keep the researcher’s hands clean but its strategy of condemnation simultaneously sanitizes the political realm and renders us insensitive to voices which are uncomfortable but politically important to hear.

____

Note: the above draws on Hilary’s new book Loud and Proud: Passion and Politics in the English Defence League, available to download here.

Hilary Pilkington is Professor of Sociology at the University of Manchester. She has a long-standing research interest in youth and youth cultural practices, post-socialist societies and qualitative, especially, ethnographic research methods. She has been coordinator of a number of large, collaborative research projects including the FP7 MYPLACE project (2011-15) which studied youth political and civic engagement in 14 countries across Europe and H2020 DARE project (2017-2020) which will investigate young people’s encounters with, and responses to, messages and agents of radicalisation.

Hilary Pilkington is Professor of Sociology at the University of Manchester. She has a long-standing research interest in youth and youth cultural practices, post-socialist societies and qualitative, especially, ethnographic research methods. She has been coordinator of a number of large, collaborative research projects including the FP7 MYPLACE project (2011-15) which studied youth political and civic engagement in 14 countries across Europe and H2020 DARE project (2017-2020) which will investigate young people’s encounters with, and responses to, messages and agents of radicalisation.