How do political parties speak to women in their manifestos, and what women do they speak to? Anna Sanders, Francesca Gains, and Claire Annesley find that while parties are increasing their appeal to women voters, there are gaps in manifesto appeals towards specific demographic groups of women, which may reflect the under-representation of intersectional voices within parties and party processes.

How do political parties speak to women in their manifestos, and what women do they speak to? Anna Sanders, Francesca Gains, and Claire Annesley find that while parties are increasing their appeal to women voters, there are gaps in manifesto appeals towards specific demographic groups of women, which may reflect the under-representation of intersectional voices within parties and party processes.

Political parties now understand that women’s votes are important and can determine election outcomes: women are more than half of the British electorate and are more likely than men to switch their partisan allegiance. For parties, there are sound rationales to make appeals to women voters during elections. Accordingly, over the years political parties have given increasing attention to ‘women’s issues’ in manifestos.

But women are not a homogenous group and their identities and issue preferences vary by – at least – age, ethnicity, sexuality/gender identity, citizenship and parental status. There is no single version of what women want from future governing parties. In a recent special issue of The Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, our question was: are political parties also understanding and responding to this?

We analysed the manifestos of Labour, the Conservatives, and Liberal Democrats ahead of the 2015, 2017, and 2019 general elections to see if and how women’s interests – in all their diversity – were being addressed. Given the importance and diversity of women voters, we expected to see two things: that the number of party pledges directed at women would have increased over time; and that the diversity of women voters addressed through party pledges would have increased over time.

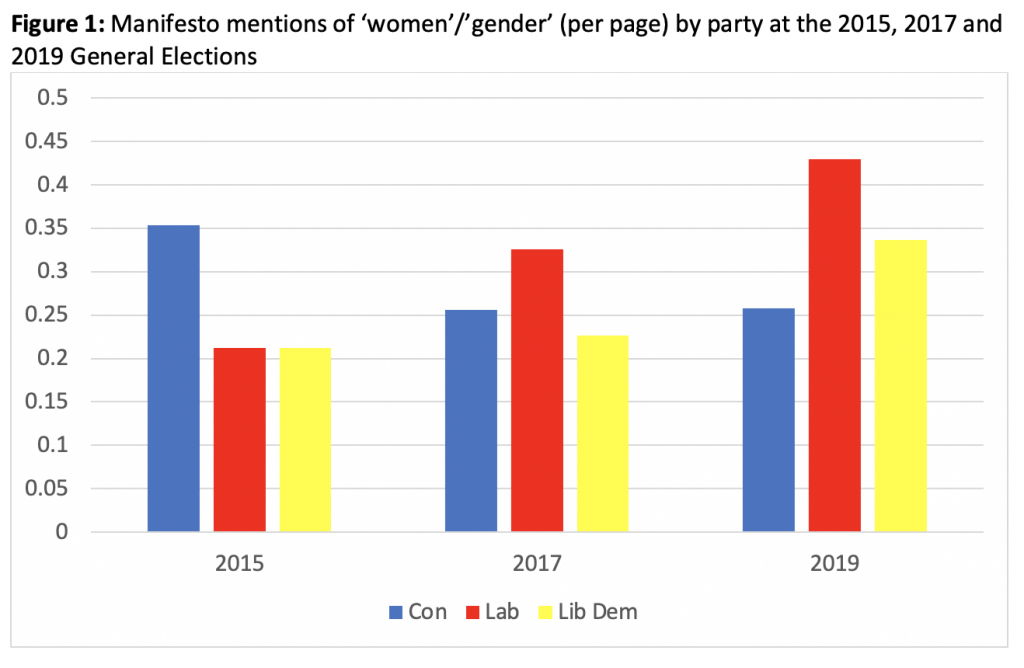

We ‘audited’ manifestos for mentions of ‘women’ and ‘gender’, counting mentions per page. We then identified more specifically which women were targeted by the policy pledges on offer to be more sensitive to intersectional differences in women’s interests and how parties are responding to these. We identified ten categories of women discussed in manifestos: women by age (older women and younger women); mothers/women with caring responsibilities; ethnic minority women; women with disabilities; women on low incomes; LGBTQ+ women; vulnerable women; women abroad; all women.

From 2015 to 2019, we found an increase in the number of appeals to women among the Labour Party and the Liberal Democrats. Meanwhile, the reverse was true for the Conservative Party, with a decrease in the number of mentions directed at women over time. There is a stark difference between parties in 2015, with manifesto mentions of women/gender much higher among the Conservative Party (0.35 per page) compared to Labour and the Liberal Democrats (0.21 mentions per page). These findings for Labour and the Liberal Democrats support our first expectation: that parties have increased their manifesto appeals to women over time.

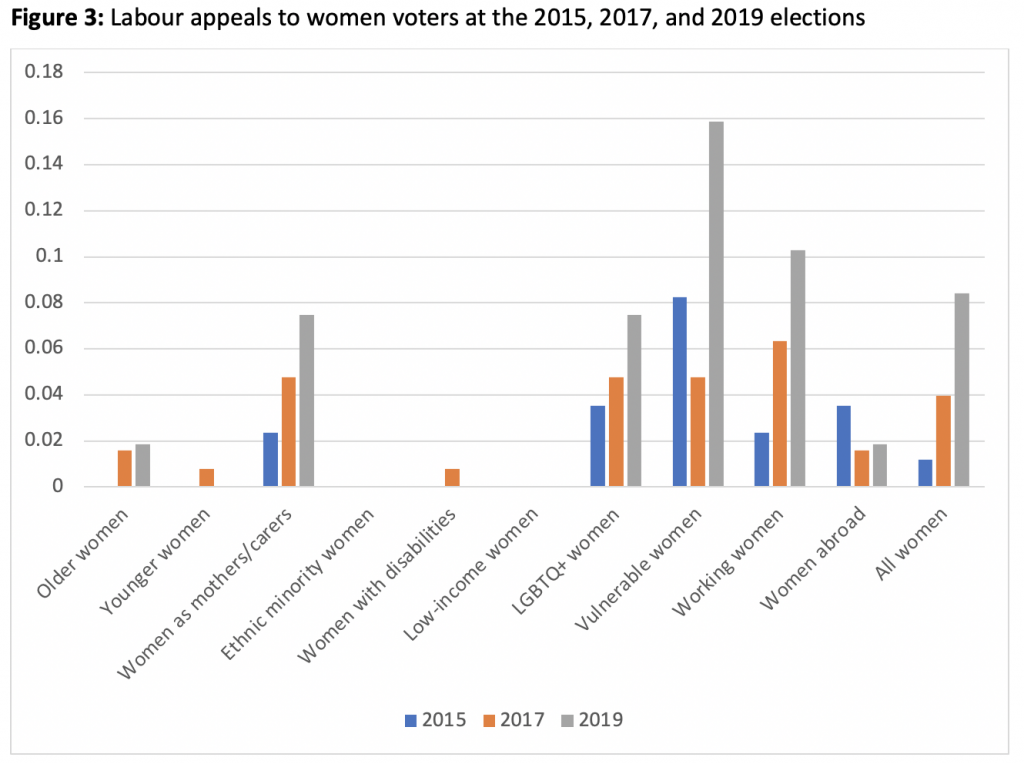

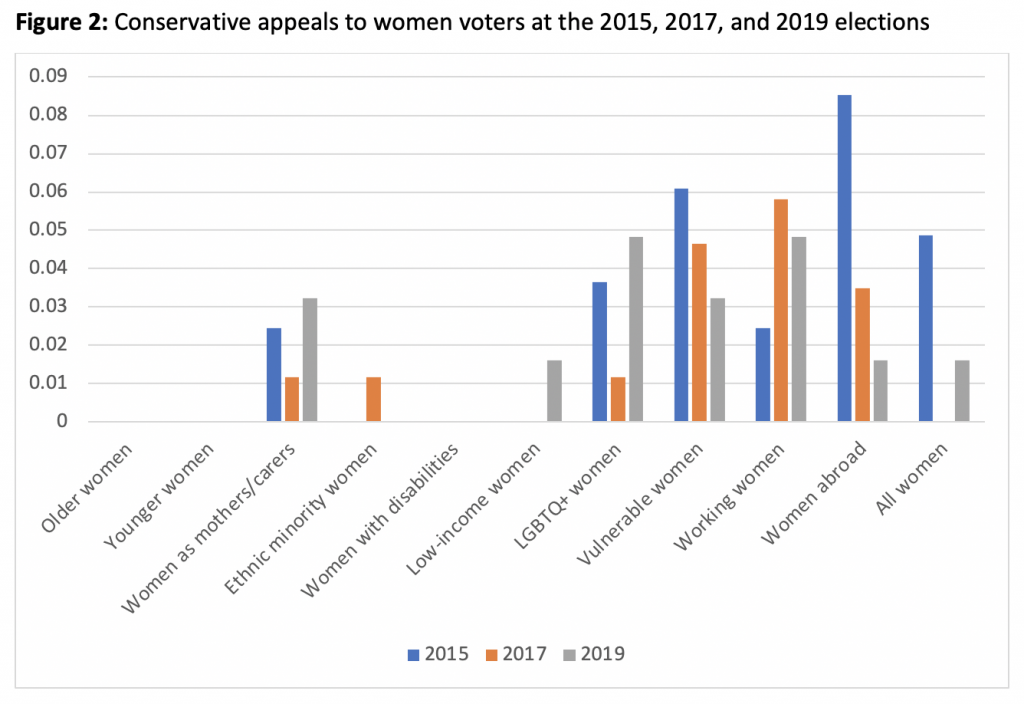

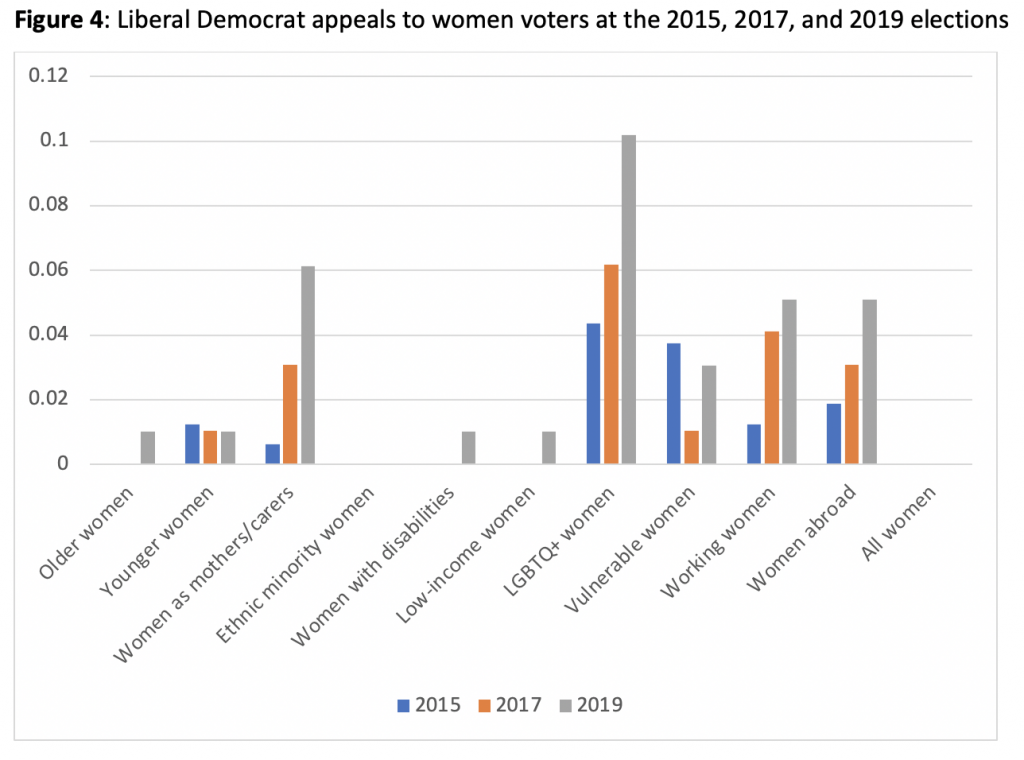

We then explored whether the diversity of women addressed through party pledges has increased over time. We found that party appeals across the three elections for all three parties appeal to more diverse women. Specifically, we found that the number of categories of women addressed across the three elections increased in the Conservative Party (6, 6, 7), as well as the Liberal Democrats (6, 6, 9), who notably address women across nearly all categories in 2019. While the number of categories of women addressed also increases in the Labour Party, there is some fluctuation across the three elections (6, 9, 7). These findings support our second expectation.

In terms of which groups of women have received increased attention, we found that across all three parties, there has been an increase in policy appeals towards women as mothers or carers between 2015 and 2019, as well as an increase in policies targeted towards working women – especially among the Labour Party. To a lesser extent, there has been a slight increase in party appeals to older women, but only among Labour and the Liberal Democrats. Finally, we find an increase in policies towards LGBTQ+ women across all three parties.

Despite growing diversity in party pledges, there are some notable gaps in appeals to specific demographic groups of women. With one exception in 2017, there are no appeals to ethnic minority women. Women voters with disabilities receive attention from just one party in 2017 and 2019. Only two parties address low-income women in 2019. Younger women also receive comparatively little attention, with very few direct appeals from the Conservative and Labour parties across the three elections.

Despite growing diversity in party pledges, there are some notable gaps in appeals to specific demographic groups of women. With one exception in 2017, there are no appeals to ethnic minority women. Women voters with disabilities receive attention from just one party in 2017 and 2019. Only two parties address low-income women in 2019. Younger women also receive comparatively little attention, with very few direct appeals from the Conservative and Labour parties across the three elections.

Also, there is a decrease in attention towards vulnerable women and women abroad. In 2015, the Conservatives offer a range of status policies towards vulnerable women, such as ending forced marriage and female genital mutilation, improving the treatment of women offenders and specialist victims’ training. By 2019, the Conservatives make just two pledges to vulnerable women. There is also less attention to women abroad from the Labour Party by 2019.

While parties are increasing their appeal to women in all their diversity, these gaps in manifesto appeals towards specific demographic groups of women may reflect the under-representation of intersectional voices within parties and party processes to develop manifestos. The marginalisation within party appeals we identify raises normative concerns regarding women’s representation more widely. If policy platforms focus on a narrow sub-section of women voters, then women’s representation cannot be fully realised. If parties wish to take women’s representation seriously, they must look beyond women voters as a homogeneous group, and recognise women voters in all their diversity.

_____________________

Anna Sanders is a Teaching Associate in Politics at the University of Manchester.

Anna Sanders is a Teaching Associate in Politics at the University of Manchester.

Francesca Gains is Professor of Public Policy at the University of Manchester.

Francesca Gains is Professor of Public Policy at the University of Manchester.

Claire Annesley is Professor of Politics at the University of New South Wales, Sydney.

Claire Annesley is Professor of Politics at the University of New South Wales, Sydney.

Photo by Pawel Czerwinski on Unsplash.