The UK’s voluntary approach towards gender equality on company boards has so far yielded results that are neither encouraging nor satisfactory, writes Giovanni Razzu. He reviews the situation and explains why the government must reconsider its approach.

The UK’s voluntary approach towards gender equality on company boards has so far yielded results that are neither encouraging nor satisfactory, writes Giovanni Razzu. He reviews the situation and explains why the government must reconsider its approach.

The European Institute of Gender Equality has recently released the update to the Gender Equality Index, which showed no progress in many areas for the UK over the past 10 years. One such area is that of decision-making power in the business sector. This is very interesting because we can look at how the voluntary approach adopted since 2010-11, when Theresa May was Minister for Equality, compares with the legislative approach adopted in other countries over the same period. The result is strongly in favour of countries who have adopted legislative measures.

The legislative approach dates back to the known example of Norway, where a 40% gender quota for public limited companies was introduced in December 2003, with a grace period until 2008 to reach the target. Female representation had increased only gradually before 2003, but then jumped from 16% in 2004, to 37% in 2007, and finally reached the 40% target in 2008.

The voluntary, self-regulatory alternative has also received wide application, the most well-known example being perhaps the UK. Theresa May, while Minister for Equality, strongly supported this approach. Lord Davies was then asked by the Coalition to undertake a review of women on corporate boards in the country. At the time of the review in 2010, women made up 12.5% of corporate boards of FTSE100 companies, up from 9.4% in 2004. That rate of increase was considered too slow. Lord Davies recommended a self-regulatory, “business-led” approach, as opposed to legislative quotas. Ten recommendations were made in 2011, the most prominent of which was that the FTSE100 boards should aim for a minimum of 25% female representation by 2015, “expecting that many will achieve a higher figure”. A steering group, also chaired by Lord Davies, was set up to monitor progress on annual basis.

The Hampton Alexander Independent review followed, with new target also for the FTSE350 and the explicit aim to “continue the voluntary business-led approach”. The latest 2016 data shows that women made up 26% of the members of corporate boards of FTSE 100 companies, an increase of 2.7 percentage points per year since 2011: a substantial improvement compared to 0.3% annual increase over the three years to 2011.

So, does the voluntary approach represent a successful way to bring about gender equality in decision-making positions in a sustainable way? I have serious doubts for three reasons.

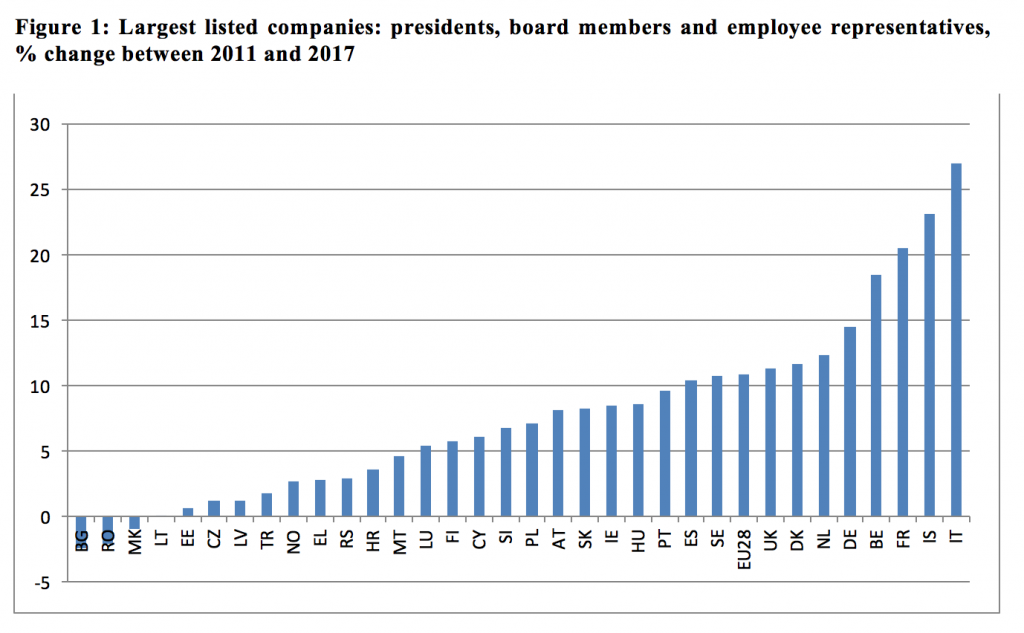

First, Figure 1 speaks for itself for whether the approach has worked so far. Figure 1 shows the progress achieved by the UK in relation to that of other EU countries, which, around the same time, have adopted legislative measures (such as France, Iceland, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Italy).

For the data see here.

For the data see here.

Two important points needs to be made when looking at the figure. There are, in fact, some countries that have adopted legislative measures and have showed less progress than the UK in the time period reported in the Figure. Yet those countries adopted legislative measures earlier than in 2011, or their legislative measures were not binding. The most appropriate comparison therefore would need to be between the UK and countries that have adopted binding legislative measures around the same period, namely France, Iceland, Belgium, and Italy.

In that case, the UK does not compare well at all. Even when looking more broadly, it is still the case that a strong association appears between the adoption of any kind of legislative measure (binding or not) and progress, even for the 2011-2017 period. Most of the countries with a voluntary approach (particularly Eastern EU countries) are on the left of the chart while those with a legislative approach (and particularly so if this has sanctions attached to the measure) are on the right side.

The second reason for questioning the voluntary approach comes from the way this has become policy in the UK. Indeed, there has been a general assumption that the voluntary approach was the most appropriate to the UK context. However, no robust assessment of the relative merits of this approach has been undertaken to date. The adoption of a voluntary approach appears to have been substantiated by an anti-legislative political will and a wide consultation with business. For instance, the Lord Davies review reported that “We have chosen not to recommend quotas because we believe that board appointments should be made on the basis of business needs, skills and ability”. The only evidence provided is the result of the pre-report consultation carried out that showed that “only 11% of respondents recommended the introduction of quotas”. No further evidence on the relative merits of the approach, or in support of these conclusions was provided.

There is also no academic work that assesses in a robust way the relative merits of different approaches to achieve gender equality on boards of companies. Quite a lot has instead focused on the issue of whether quotas are detrimental to business performance. However, once it is agreed that the objective is to increase gender equality on company boards, the question becomes one of assessing the best option available to achieve the set objective.

In fact, there are signs that even this relatively limited progress achieved to date might not be sustained in the near future, making sustainability the third reason for doubt. For instance, The Female FSTE board report by Cranfield back in 2015, suggested that the proportion of women on boards of FTSE100 companies would peak at 28% in 2018 and then fall slightly. Other reports from both Lord Davies’s annual reviews and Cranfield’s reports indicate that the progress to-date has been a result also of the important role played by key figures in the debate and by a constant communication and stakeholder engagement strategy. The potential lack of these key components in the near future also raises doubts about the sustainability of the approach.

Lord Davies in his first report said: “Government must reserve the right to introduce more prescriptive alternatives if the recommended business-led approach does not achieve significant change”. I think it is time to reconsider the merits of legislative measures to achieve more gender balance in the boards of our companies. Countries that have adopted legislative measured have done much better than us. Why should not we aspire to the same?

________

Giovanni Razzu is Professor in Economics of Public Policy and Head of Department of Economics at the University of Reading.

Giovanni Razzu is Professor in Economics of Public Policy and Head of Department of Economics at the University of Reading.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Pixabay/Public Domain.

In November 2012 the Sutton Trust produced a report—“The Educational Background of the Nation’s Leading People”—on the over-representation of privately-schooled people in the top jobs in the professions in the UK.

About 58% of top jobs in business/financial services in the UK are filled by individuals who were educated at private schools. Yet just 7% of the UK’s children attended private schools.

Is there an social-class element to gender equality in British businesses? It is not possible from Sutton Trust report to work out how the top jobs in British business are split between men and women. Are the (slowly) increasing number of women getting top jobs educated in private schools like the men? Are talented women educated in state schools recruited for top jobs?

Dear Arthur

you raise a very relevant pint about the interaction between gender and social class. It could be possible to look at this, in a couple of ways at least: data from companies websites – note that the Narrative Reporting Regulations that came into force in 2013 led most companies to include the information on gender breakdown at board, senior management and the total workforce, integrated with analysis of CVs when available; other data, which is privately owned and therefore would need to be acquired, which contains detailed information on socio-demographic characteristics of members of boards (educational qualifications, age, ethnicity, date of appointment, employment history etc.)

I’m involved with setting up a gender equality network at my company – launching in 3 weeks. Picking up your example of Norway, is there data or research on the post-quota achievement performance of the economy / companies? It woild be a good alternative context to discuss the inevitable questions raised concerning what happens when the men who would have got the role aren’t promoted because a woman gets in.

Dear Louise

here are some papers that have looked at the impact of gender quotas on business performance, which you may find helpful:

Adams, Renee B., and Daniel Ferreira, 2009, Women in the boardroom and their impact on governance and performance, Journal of Financial Economics 94, 291–309.

Ahern K., and Dittmar A. (2012) ‘The changing of the boards: the impact on firm

valuation of mandated female board representation’, Quarterly Journal of Economics,

Volume 127, Issue 1, pp. 137-97.

Campbell, K., and Minguez-Vera, A. (2008) ‘Gender diversity in the boardroom and

firm financial performance’, Journal of business ethics, Volume 83, Issue 3, pp. 435-

51.

Engelstad, F. and Teigen, M. (2012) Firms, Boards and Gender Quotas: Comparative Perspectives (Emerald, UK).

Farrell, Kathleen A., and Philip L. Hersch, 2005, Additions to corporate boards: The effect of

gender, Journal of Corporate Finance 11, 85–106.

Hoel, M. (2008) ‘ The quota story: five years of change in Norway’, in S. Vinnicombe, V. Singh, R. J. Burke, D. Bilimoria and M. Huse (Eds.) Women on Corporate Boards of Directors: International Research and Practice. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

hope they are helpful in some way.

giovanni

Question begged: Why is it ‘agreed that the objective is to increase gender equality on company boards’ as opposed, for instance, to appointments being made ‘on the basis of business needs, skills, and ability’? Who agreed this objective, when?