If personal prayer is a private matter, why should social scientists consider it in their research? Anishka Gheewala-Lohiya reminds us that the majority of the world’s population is religious. She also stresses the widespread practice of prayer across different religions, and argues that the religious observer’s active ‘secular’ life cannot be easily distinguished from their personal religiosity.

If you say ‘I study religion’, people often give you a quizzical stare. Sometimes, they prompt you to continue ‘and…? Politics?’ Religious life and the wider world are interrelated, but in order to understand how they are connected it is essential to understand each domain in its own right. This is the only way in which an academia heavily influenced by the Enlightenment can seriously engage with religion as a research topic.

The Enlightenment thinkers of the 18th century foresaw a shift towards rational thought wherein a decline in religion would slowly lead to the secularisation of society. On the contrary, we have seen that religion remains a part of everyday life, whether one ascribes to a faith or not. It is a well-debated and documented discussion.

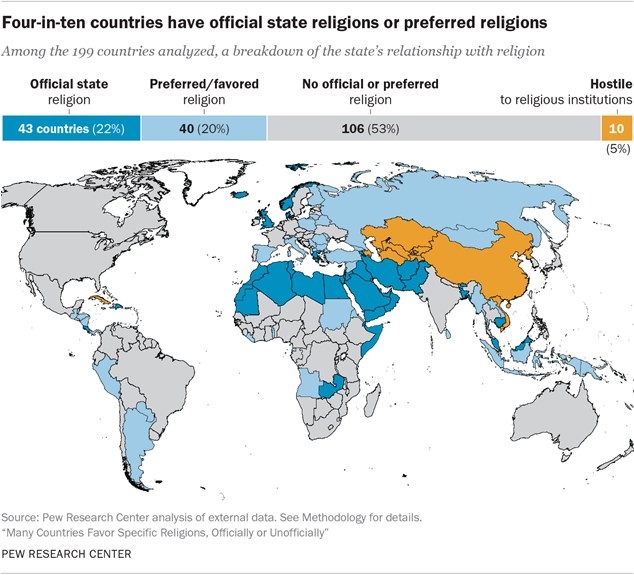

A recent survey by the Pew Research Center suggests that the clear majority of the world’s population identifies with a religion. Another Pew survey looks at how some seemingly-secular states give benefits to certain religions over others, among other examples of religion in everyday life.

In this article, I focus on the idea that prayer as a religious practice does not separate the devotee from the ‘secular’ sphere they inhabit. As such, prayer can be a useful analytical tool of religious life for any scholar in the social sciences.

Prayer

Eyes closed. Deep breaths. Hands clasped together, head slightly bowed. Isn’t this an outward sign of prayer we all recognise?

While we can observe parallels in basic religious practice, for example Catholics and Hindus lighting incense and candles, there are also obvious differences in religious worldview such as notions of the afterlife and how people should lead their lives. We cannot make sweeping generalisations about religious practice. Religion is in continuous change, from “traditional” religions such as Christianity, Judaism, Islam and so on, to New Age movements, exposing a diverse religious landscape across the world, including within individual religions.

Prayer is a common factor in the world of religious behaviour despite the fact that the word itself has a Latin and French background, implying Christianity as the source of the concept. A prayer is commonly defined as either a petitionary act requesting something from the divine, or a demonstration of gratitude giving thanks to the divine.

Anthropologists have focused on the rituals of religious communities since the discipline began (Durkheim, Weber etc.). Yet outside of theology and religious studies there is a rather large gap in the study of personal prayer in academia. Why has this not been addressed?

I suggest that there are three main reasons for this.

1) Prayer as private

The idea that prayer is personal, private and internal can be seen as a legacy of the private/public religious debates of the Enlightenment, where religion was considered part of the private life of an individual, set apart from the secular public life. As we know, these two worlds often collide and interact, both for individuals and communities.

Ritual is far easier to see. We can observe what people are doing quite clearly. People in church read hymns, use prayer beads and bow their heads. People in mosques prostrate themselves, bow their heads and recite Koranic verses. In Hindu temples there is a full sensory experience involving flowers, incense, blessings and food. Rituals can be a way of communicating with the divine. However there is a routinisation and prescription of ritual which limits the idea of spontaneous or creative prayerful communication with the divine.

2) The role of a researcher

In projects regarding personal matters researchers must tread carefully. People can find it uncomfortable discussing their intimate life stories with a complete stranger in the first place, let alone how they talk to God in their mind or through other practices. This is also part of a discomfort of studying religion in general, where the social scientist fears overstepping invisible boundaries and being seen as intrusive, particularly with the background knowledge that it will be written about and analysed in a public forum. In my research, the question of my own belief comes up frequently, and can bring me closer to people or push me away.

3) Prayer is difficult to define

Finally, defining the practice of prayer is a fruitless challenge. While prayer as a concept may be comparable through religious experience, the definition of prayer is limited if we consider the request or gratitude definition as the clear meaning of the word. So rather than debate what prayer is, I suggest we move away from this restrictive view and begin to look at prayer practices themselves. In this vein, Fenella Cannell poses the question, “What counts as prayer?” The history of prayer as outlined by the Britannica website gives an indication of how extensive and varied prayer can be. However, as with my research, it concludes that prayer is about dialogue of some form.

Prayer is a common feature of many faiths; the idea that worship is about communicating with God, or the divine more generally. Prayer seen as communication, rather than a petitionary act, is a way to look comparatively at how different faiths communicate with the divine, and how they envision the world based on this relationship. Therefore, this influences how they behave and act in the world.

Does God talk back?

Miracles are cited as “proof” of God’s existence. Marian apparitions and weeping statues of the Virgin, for instance, have been widely reported for centuries. The media portrays such perceived miracles as either a hoax, a mystery or, particularly in religious media, true signs of the divine.

A powerful example of God ‘talking back’ was evident among the Hindu diaspora when hundreds of communities across the world were connected by the apparent phenomenon of the elephant-headed god Ganesha drinking milk offered up by devotees. This story spread rapidly, with people rushing to get milk to try it on Ganeshas in temples and homes. The word ‘miracle’, like prayer, has its roots in the Christian world. Miracles are commonplace in Hinduism, with people believing in everyday miracles rather than once-in-a-lifetime proof-of-God miracles more commonly associated with Christianity.

Prayer is a sign of belief in the divine, however people pray. Through meditation, words and songs, ritual and routine, believers do not necessarily need a visible “proof” of God’s existence in order to continue to pray. This is a part of many peoples’ daily routine and must be considered if we are to understand how their worldview is shaped. Rather than continually debating the religion/secular divide, it must be acknowledged that both spaces form part of the devotee’s daily existence. How believers formulate their religious perspective can influence how they live their so-called “secular” public life.

About the author

Anishka Gheewala-Lohiya is currently a PhD candidate in the Anthropology Department at LSE working on prayer and Hinduism in India and the UK diaspora.

Anishka Gheewala-Lohiya is currently a PhD candidate in the Anthropology Department at LSE working on prayer and Hinduism in India and the UK diaspora.

Note: This piece gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Religion and Global Society blog, nor of the London School of Economics.

Please explain the mechanism by which the believer’s prayers reach the hypothetical god or gods.

Hi Alan,

I would suggest that the diverse range of religious movements have developed their own particular system for prayer. This system is powered by belief itself, therefore, a ‘mechanism’ is not really in place, rather individual or collective belief powers the prayer that believers would understand to reach gods or god.

Thanks!