The fundamentalist label is used widely in religion reporting but can be a simplistic description that suggests similarities between very different groups that span traditions and generations. Alex Fry considers the label’s historical emergence in Protestant America, its widespread use ever since, and why less succinct but more accurate language should be used when describing religious groups.

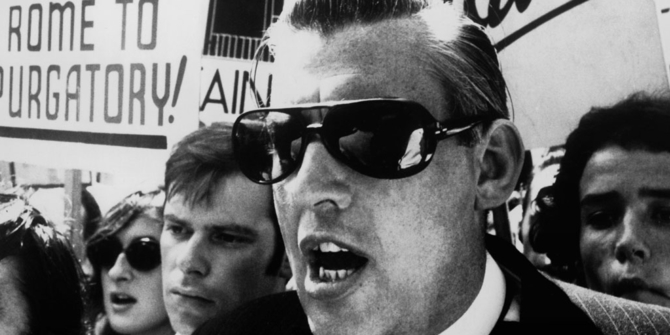

In the public sphere, discussions on religion are frequently accompanied by presumptions about ‘fundamentalism’ or ‘fundamentalists’. One does not have to delve deeply into the media to find articles on so-called Islamic fundamentalists who are discussed alongside terms such as ‘extremist’ and ‘terrorist’. Equally, the word ‘fundamentalist’ is associated with certain strands of Christianity which are often labelled as hateful, such as the infamous Westboro Baptist Church, widely known for its message of divine vengeance.

Nevertheless, there are a number of intellectual shortcomings with the way in which the word is often used, meaning that public discourse on religion is likewise lacking in intellectual rigour. These have been documented elsewhere by scholars such as James Barr, Martyn Percy, Steve Bruce, and Kathleen Boone, some of whom still apply the term, and need not be recalled here. However, one shortcoming of the way in which the term ‘fundamentalism’ is used is the lack of understanding surrounding its historical emergence. This leaves much discussion on so-called fundamentalist religion largely divorced from its origins. This is particularly problematic because, unanchored from its original meaning, the term can be used in any number of ways.

In order to understand how the term ‘fundamentalist’ developed, it is necessary to begin in the USA at the start of the twentieth century. By this point in time the historic teaching of many Protestant denominations was understood by numerous Christians to be under threat. Beliefs considered by many to be integral to the Christian faith were being questioned. This led a group of evangelical Christians to produce a series of pamphlets entitled The Fundamentals between 1910 and 1915. Each one addressed a different theological concern and was written to reinforce traditional Protestant beliefs.

By the 1940s, this had produced a distinct group of evangelicals who, in keeping with the theology of The Fundamentals, self-identified as ‘fundamentalist’. This group of Christians was separatist. In other words, they tended to disengage from the public sphere, establishing their own educational institutions. They even separated themselves from mainline Churches due to the theological liberalism that this group of evangelicals believed they possessed.

A rather different use of the term emerged in the 1970s. The Iranian Revolution saw the overthrow of the country’s monarch and the establishment of an anti-Western theocracy. Commentators at the time referred to the religious sentiments of those in support of the new political system as ‘fundamentalists’. Around the same time, a group of evangelicals entered public discourse in the USA. Unlike the ‘fundamentalists’ from the first half of the twentieth century, this group became politically involved in a significant way. A series of laws had been passed by the US government during this time which were interpreted as federal infringement of religious liberty. Specifically, tax-exempt status was removed from private educational establishments (including evangelical colleges and universities) that resisted racial desegregation. This sparked a wave of protest, not only on this matter, but on a host of religious, social, and political concerns. This was considered to be a new phenomenon within evangelicalism by those who observed this group of Christians from the outside. Both scholars of religion and the press called these evangelicals ‘fundamentalist’.

Since then the word has taken on various meanings. In the British media, for example, the term lacks a specific definition. A quick search shows that in The Guardian alone, depending on the article, it is associated with those who believe solely in moral absolutes, those who hold views considered to pose a threat to women, and those who belong to the religious right in the USA. In The Telegraph, depending on the writer, it is used in conjunction with those who belong to polygamous sects who believe in a literal apocalypse, or to expressions of Islam deemed to be extremist and politicised. While there may well be some overlap in beliefs or values between many of the groups identified as ‘fundamentalist’, they are all evidently distinct, a fact that is not implied by the use of the label.

It is important to rethink how traditions labelled ‘fundamentalist’ are described. While different solutions have been offered, one possibility is to define a group of devotees in line with the broader tradition of which they are a part. Many religious groups are part of larger religious networks, institutions or traditions. For example, my previous research explored the gender values of evangelical clergy in the Church of England. While some of their beliefs are often associated with ‘fundamentalism’, most beliefs weren’t, and so they were defined with more specific and accurate terms. For example, one group was described as conservative evangelical Anglican.

To break this down, the term ‘conservative’ was used because, in line with other research on conservative evangelicalism, many of my participants’ beliefs were in keeping with the historic nature of evangelicalism and were re-articulated in opposition to more liberal theological beliefs. The term ‘evangelical’ was used because, unlike with ‘fundamentalism’, there are several criteria that are consistently applied to evangelicals, such as the emphasis on personal conversion, the centrality of Jesus’ crucifixion, the importance of proclaiming the Christian gospel, and the supreme authority of the Bible. Being part of the Church of England, they are also Anglicans.

While this approach leads to less succinct descriptions of religious groups, it provides a more accurate one and so it permits more constructive dialogue on religion, not least because the subject being discussed is clearer. The ability to identify social groups is necessary in the social sciences if we are to talk meaningfully about our society. However, they are only helpful insofar as they allow us to discuss social phenomena accurately. This means that the descriptions we employ should help us to see religious traditions and those who are a part of them as fully as possible. When they do not do this, their utility ought to be questioned and more suitable language considered.

Note: This piece gives the views of the author(s), and not the position of the LSE Religion and Global Society blog, nor of the London School of Economics.