From Brazil to India, Hungary to China, governments on the political left and right are using anti-pluralist sentiment to further their agenda. Based on his recent journal article, Robert Joustra examines the importance of social and political pluralism in societies, proposing a new framework to examine the topic.

Every age has its peculiar obsessions and fixations, some perennial, some novel. Pluralism, and the small cottage industry that its definition and practice has grown, is a little of both. The question of diversity—how much is too much? how to structure it? how to make society cohere?—is hardly original to the modern world. But our mass, global awareness of foundational diversity, coupled with the idea that it is a moral good that such diversity should coexist in a society, rather than in its own discrete societies, is a relatively new idea. Sure, we had the pluralism of Ashoka’s Rock Edicts, or the imperial pluralism of Rome, but the latter tends to be the world historical rule much more than the former. This suggests diversity is good insofar as it supports a particular arrangement of social and political power.

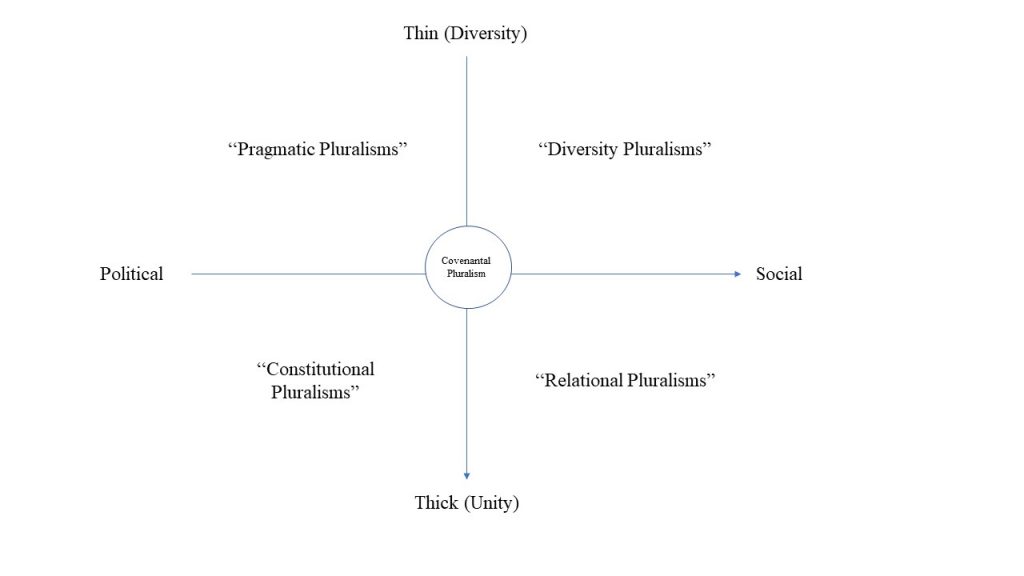

How do we talk about this explosion of pluralist sentiment? Where does one begin, in a sprawling and–ironically–divisive literature, to get a handle on contemporary debates in pluralist theory, and a conceptual map of the philosophical terrain? This was just the question that Stewart, Seiple, and Hoover asked in their recent RGS blog and their new initiative at the Templeton Religion Trust on “covenantal pluralism.” And, as I discuss in a recent article in The Review of Faith & International Affairs, I have developed a quadrant to plan and plot the confusing array of pluralisms.

Beyond a Spectrum: The Pluralisms Quadrant

Today, the “left right spectrum” in political theory has lost much of its meaning and may be more misleading than it is clarifying. Both “left” and “right” states around the globe are busy embracing anti-pluralist, sometimes nationalistic, programs: from Bolsonaro’s Brazil, to Victor Orban’s Hungary, to Modi’s India, to Xi Jinping’s China, there is an empirical pivot against pluralism from various ends of the spectrum. What room remains for the pluralists?

The quadrant that our project uses as the context for rehabilitating pluralism therefore uses not one, but two axes, and it does not use conventional “left” and “right.” On the first axis, we talk about political vs. social pluralism, or, as some might say, “top down” vs. “bottom up” pluralism. The key distinction here is who are the actors that guarantee or safeguard pluralism. On the social side of the axis you find those skeptical of political power, or the “politics is downstream of culture” crowd, who argue that ultimately coexistence is only possible amidst vigorous social engagement. Here we also find critics of tolerance. Tolerance, argue the social pluralists, is just enough to get folks to irritably coexist with each other, but not enough to use diversity as a strengthening glue for common projects. Grassroots, social engagement is essential. Political pluralists, on the other hand, default more to the processes and institutions of the state, its courts and constitutions. They focus on the “rules of the game” which enable fair play.

On the other axis, I talk more about the quality of pluralism: “thin” vs. “thick.” This is what I call the gambling axis: how much trust do you have in your fellow citizen? Do you need a thin set of ground rules, a small number of pragmatic areas of alignment, that can carry the project of social and political order? Or do you need a thicker set of ground rules, more robust rules for engagement, more structured and coerced rules and norms? The answer is impossible to give in the abstract. It depends – as those like Fukuyama have argued – on the balance sheet of your social reserves, trust. It depends on which society, which people, and which diversity is being adjudicated.

Abstract as these axes may be, they produce four quadrants that yield a coherent map of the pluralist territory. Quadrant 1: Diversity Pluralisms; Quadrant 2: Relational Pluralisms; Quadrant 3: Constitutional Pluralisms; and Quadrant 4: Pragmatic Pluralisms.

Quadrant 1: Diversity Pluralisms, is a thin/social quadrant, home to many traditional postmodern theories of pluralism such as William Connolly’s agonistic pluralism, Mahmood and Hurd’s difference pluralism, and even Jocelyn Maclure and Charles Taylor’s pluralist political secularism.

Quadrant 2: Relational Pluralisms, is defined by being primarily, though not usually exclusively, social. Pluralisms here include Diana Eck’s Harvard Pluralism Project, Eboo Patel’s courageous pluralism, and John Inazu’s confident pluralism (which also spans Quadrant 3). This is the quadrant in which we find most approaches we might call interfaith.

Quadrant 3: Constitutional Pluralisms, is characteristic for its political emphases but also because it tends to foreground concerns for unity which, it argues, enables the kind of diversity we might reasonably call pluralistic. It rejects the idea of relativistic “neutrality” in public life and embraces that certain kinds of principles or constitutional limits will be necessary. This shapes the kind pluralism practiced and acknowledges that the limits may be open to change or revision from time to time. This includes authors such as Os Guinness and thinkers in the Kuyperian tradition such as James Skillen, Jonathan Chaplin, Stanley Carlson-Thies, and many more.

Quadrant 4: Pragmatic Pluralisms adds something fundamental to the conversation on pluralism that has so far been implied but hardly named explicitly: namely, that there are some practical, common objectives that human beings, regardless of how deep their pluralisms run, share. Authors I would categorize within this quadrant include, for example, Laurie Patton, Jaclyn Neo, and Rajeev Bhargava. I have also come to think of this quadrant as pandemic pluralism. Pandemics, as the Covid-19 pathogen proved, require practical alignment across a diversity of interests. The pandemic witnessed some pragmatic pluralism, where deep diversity was shelved for the moment, to attend to the crisis of the pandemic. But we also saw the limits of pandemic pluralism, where deep diversity was used by muscular and pragmatic efforts to foster division amidst ongoing culture wars.

Covenantal Pluralism at the Crossroads

What does this road map to pluralism give us? First, it shows clearly what is at stake in the many accounts of pluralism over the last several decades, and it flags sometimes irresolvable tensions in the abstract: between thickness and thinness, and between social and political axes. It shows, in other words, that pluralism is actually not best left to pure theory but to practice; it is hard to debate in the abstract and actually easier to apply in the real. It is impossible to tell what exactly the ideal pluralistic arrangement might be, as too much depends on the time, place, and people in which that arrangement is meant to serve.

Second, it also shows how important the fundamental social currency of trust is, whether that is in interfaith exchange, or political collaboration. Good systems and institutions may make good neighbors, but good neighbors also replenish and revitalize those same systems and institutions. There is no social or political substitute for the breakdown of social trust. Pluralism cannot long survive in a society where trust has broken down.

All of which points, in my opinion, to the important new concept that Stewart, Seiple, and Hoover have developed—covenantal pluralism—which is a holistic vision combining constitutional commitments to equal rights and responsibilities and cultural commitments to reciprocal engagement, respect for human dignity, and solidarity. As their contribution shows, covenants are intrinsically dynamic; they are made in situ. They are negotiated by human beings, in relationship, and they structure settlements and disputes. In my quadrant, I have optimistically placed covenantal pluralism at the center of the axes, but in many ways the strength and resilience of covenantal pluralism is that it is not a static set of outcomes, but rather a process. It is a whole way of thinking about and practicing political and social pluralism. In its aspirations it is perhaps preciously idealistic, but in its practice, it stands at a crossroads of methods and measures that have stood the test of time.

Note: This piece gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Religion and Global Society blog, nor of the London School of Economics.

Thanks for this article, Rob. That helps me understand our present time better and it gives me hope that we can move forward together. If I am in error, I prefer to err on the side of optimism.

Blessings on your continuing work. Herman

Thank you! I am working on my PhD dissertation about FoRB and gender equality. I was intrigued by your definitions of thick and think pluralism. I also like to use the terms robust or rigid. I found your blog helpful and plan to quote you. Meanwhile, I developed a 60-minute e-course about religious freedom for people in the MENA region that might interest you. Please check it out when you have a moment. I welcome your feedback: https://human-rights-and-religious-freedom-training.teachable.com/p/home

Best wishes!

Shirin Taber

http://www.empowerwomen.media