Across denominations, churches serve as a liminal space between the secular and sacred; they embody religious practices and eternal symbols while operating in the world as it is. In this post, Dr Efstathios Kessareas writes about the difficult balance Christian churches make between this sacred transcendence and modern society. An example of this, Kessareas focuses on the Orthodox Church in Eastern Europe, exploring the entanglements churches have with nation-states.

Jesus responded to Pilate: “My kingdom is not of this world…[it] is from another place” (John 18:36). In this way, he drew a clear boundary between the divine (spiritual) and the worldly (political) realms of existence, highlighting their different character: the first as qualitatively superior to the second, for it is linked to the ultimate criterion and state of truth.

Christian Churches, however, despite their self-perception as godly institutions of an eschatological orientation, are historical products. What is more, in the course of history, they have developed and established themselves as major structures of this world. The most obvious implication is that they must unavoidably relate to the various domains of the world (e.g. politics, economics, culture), even when they theologically reject, accept or attempt to transform them according to Christian principles and values.

This fact places significant pressure on them; the greatest challenge is finding an appropriate balance between the realm of transcendence, which stands at the core of their identity, and the urgent necessities of the existing social order, avoiding the danger of a total identification with the latter. However, the boundary between ‘positive’ world-engagement and ‘negative’ worldliness (commonly associated with secularization) is not always easy to identify or maintain.

This becomes more evident when Churches adopt methods and strategies of the contemporary broader social environment in order to disseminate more effectively their own message and increase their members. The difficulty arises from the fact that these ‘tools’ and practices are not neutral. On the contrary, they are closely intertwined with secular, pragmatic, and individualistic ideas and values (e.g. market ones), which are in opposition to the religious, metaphysical, and holistic beliefs and values of the ecclesiastical organizations (e.g. salvation, eternal life, temperance, repentance, personal relationships based on love, philanthropy, and solidarity).

Although the challenge of worldliness mostly concerns Western Christianity, particularly in its Evangelical forms, it is not unknown for Orthodox Christianity too. This should come as no surprise, since Orthodox Churches participate actively in the modern world and are also affected by the socio-economic transformations of the latter. Two illustrative cases are the development of profitable religious tourism by Orthodox Churches and modernization that is presently occurring in the monastic community of Mount Athos; contrary to what might have been expected from such traditional monasteries, they use modern technology to digitize their cultural heritage and provide their various monastery products for online selling.

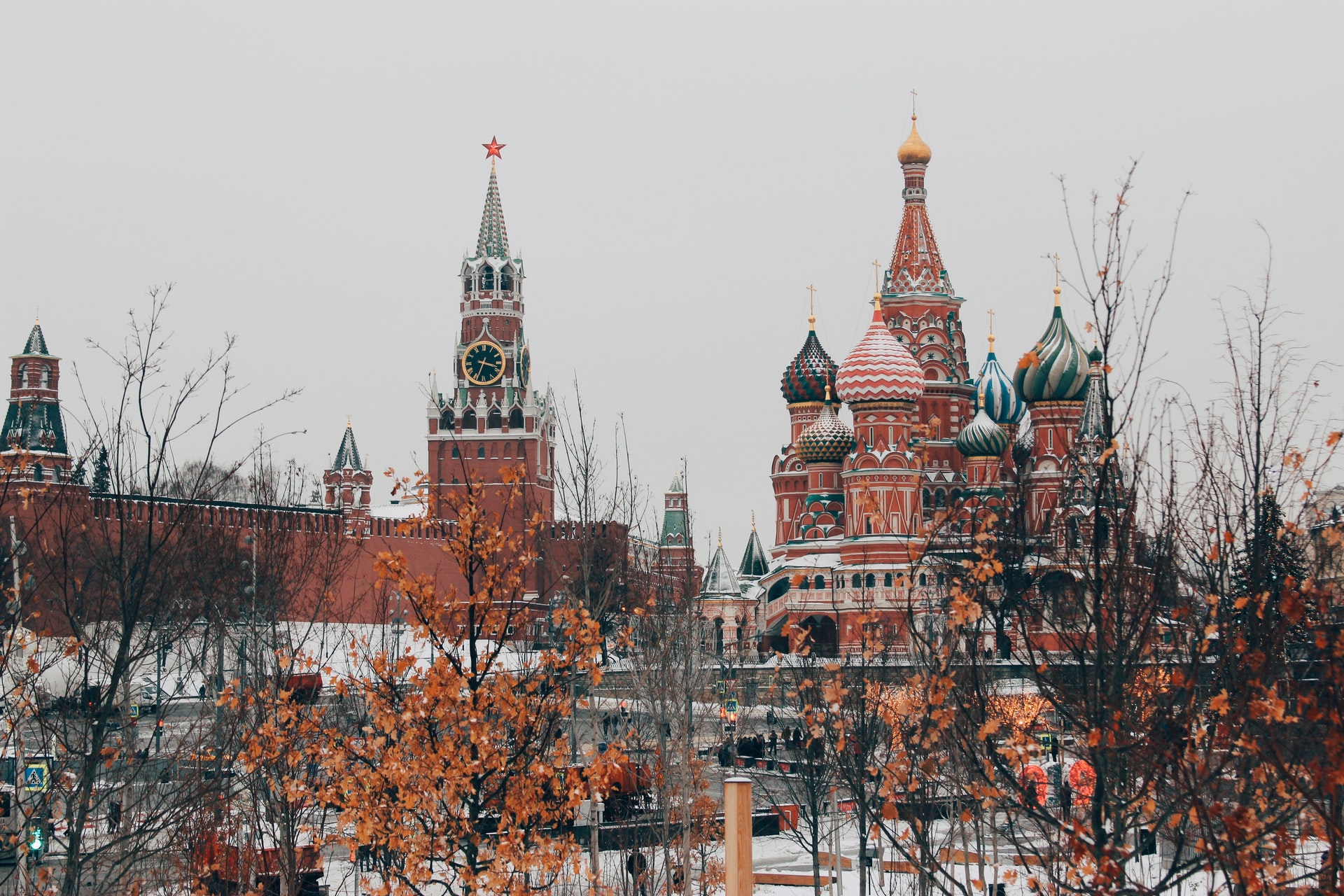

However, for the Orthodox world, it is the identification with the nation-state that poses the greatest threat to its liturgical and mystical spirituality. A comparative look into the websites of the Evangelical Church in Germany and the Greek Orthodox Church suffices to indicate their different character and orientation. Whereas the first places the issues of modernization, digitalization, and virtual church life at the forefront, the second highlights more traditional topics, such as institutional and national ones. The special thematic unit concerning the role of the Greek Orthodox Church during the National Revolution of 1821 is a prime example in this respect. Even the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America, which functions within a more multicultural religious and cultural environment, has launched a similar website, scheduling analogous events in the context of the celebration of the 200th Anniversary of the Greek Revolution. As it is well known, Greek diaspora finds in Orthodoxy a significant means of creating and preserving a sense of national identity.

This by no means implies that Orthodox Churches underestimate contemporary developments or that they do not address social problems. Their acts of charity during the financial (since 2009) and refugee (since 2015) crises, as well as the recent formulation of a document that has a more liberal spirit on social issues, prove the exact opposite conclusion. But the point is that Orthodox Churches, especially those from Eastern Europe, arrange these concerns in a different hierarchy, one in which the nation remains the center of gravity.

Their national character has deep historical roots; first and foremost, their formation as national churches after the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire. Hence, they perceive themselves as ‘arks’ of the nations to which they associate. This is an embedded self-image that mutatis mutandis places the nation as another ‘holy entity’ next to that of the religious sacred. Here, religious transcendence is not pushed into the margins because of accommodations of the churches to the worldly spirit of the time (secularization, modernization, etc.), but it acquires a Siamese twin that has the same holy blood, namely the nation.

As both kinds of the sacred result from and serve the same collectivity to which they refer to, their entanglement can be functional – and actually, it has been in specific historical periods (e.g. the Greek case in the context of the 19th and early 20th century nationalism is a prime example). Today, however, tensions arise as the modern values of differentiation and multiculturalism are at odds with the ‘sacred demand’ for national exclusiveness and homogeneity. In this context, the treatment of Orthodoxy as an instrument for political or ideological purposes is no longer accepted as valid, but rather is often denunciated as alienation from its core transcendental spirituality.

Undoubtedly, the continuous crises of our times pose new challenges to Christian Churches. As they attempt to respond to these by employing the means and discourse of the secular environment, a state of worldliness appears to threaten their spiritual identity. The growing number of conversions to Orthodox Christianity can be interpreted in light of a search for a deeper spiritual experience beyond the enhanced worldliness of Western Christianity. On the other side, the national character of the Orthodox Churches comes under severe criticism especially from actors in Western multicultural societies, who wish Orthodox Churches and theology to become more open.

Although no one can predict future developments, there can be little doubt that the specific character of each Church is shaped by the kind of response it gives to the problem of the relationship between the transcendent sphere and the everyday mundane affairs. However, this is an open-ended process, the outcome of which depends on the internal antagonism among the various layers that comprise every church community, as well as on the ideological influences from the broader social environment.

Note: This piece gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Religion and Global Society blog, nor of the London School of Economics.