Contested authority has been an emerging theme in our coverage of religion and COVID—19. Religious community responses to the pandemic have ranged from unwavering commitment to public health measures, to outright disregard of such rules, and much in between. Anna Koulouris shares with us her personal perspective as a Jerusalem-based employee of the Greek Orthodox Church. Within the unique context of an unusually religious city, the Church has drawn on its historic presence in the region to successfully sustain cooperation with public officials while balancing its duties to the wider public.

As the coronavirus spread, questions that we took for granted as theoretical undercurrents to daily life became relevant and immediate. Perhaps the most difficult to answer has been to what extent worldly authorities should ever be able to dictate how we fulfill our obligations to God.

As an American living in Jerusalem and working for the Greek Orthodox Church, watching this question play out has been quite revealing. This religious center, where religious identity is arguably the primary identity, is the ultimate litmus test when it comes to matters of the human and the divine functioning in the same space.

Admittedly, Jerusalem on a regular day functions a bit outside the spectrum of the rest of the world. Almost all activities in the city and surrounding areas are dictated by religious calendars. There is an ever-present backdrop of spiritual matters in the air, where biblical history blends into current events. Perhaps for this reason, while the rest of the world reacquainted itself with stories about the 1918 Flu and the Black Plague, it felt that people in the Holy Land were not so startled by the prospect of plague, but rather, how they would continue to worship.

There has been a lot of criticism directed toward institutionalized religion in the days since the pandemic took hold, and understandably so. We’ve heard stories of Christian leaders around the world, for example, who defied public safety orders and continued to gather; some even vowing to gather in larger numbers than before in a sort of simultaneous protest to authorities and appeal to God. But a much-overlooked example has been the Christian handling of public worship amid lockdown in the holiest of places. A month after Easter, church conduct in the Holy Land was locally considered largely a success story, not only by believers but the political authorities, too. Israel and the Palestinian Territories have flattened the curve of virus cases to a near standstill, and the local faithful and Church leadership have not expressed religious freedom grievances. This is not the case in the United States, where numerous lawsuits have been filed, nor in Greece, where a Greek Orthodox metropolitan was arrested for holding services.

Taking a closer look, some context is needed. The build-up to Holy Week over the forty-day period of Great Lent ran almost exactly parallel to the build-up of fear and unprecedented restriction that followed news of the coronavirus spread. By 5 March, Israeli authorities closed West Bank borders, beginning with Bethlehem, ordering all foreign visitors to leave the entire region, and flights to cease. By the time every inhabitant of Israel and the Palestinian Territories had been confined to their homes for more than a month it was the pinnacle of the Christian liturgical year – the Holy Light service on the eve of Easter Sunday.

On this day, according to the more than 1,000-year-old tradition, the Patriarch of Jerusalem, who is the pastoral successor of Saint James the Apostle, enters the site of Jesus Christ’s burial and is sealed within its doors. After reciting ancient prayers, he emerges from the tomb with a flame representative of Christ’s victory over death. The flame, considered miraculous, spreads to more than 10,000 pilgrims packed within the Church of the Holy Sepulcher and then to tens of thousands of people throughout the Old City streets. Priests with lanterns race off to neighboring cities, and ambassadors of Orthodox countries promptly send their own lanterns off on airplanes back to their home countries. Youth marching bands parade through the streets, young men ride each other’s shoulders chanting through the quarters, and music is blasted on sound systems over the city. Jerusalem is full, colorful, and packed with noise and celebration.

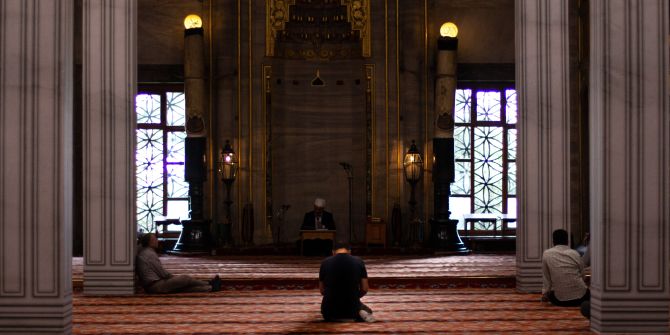

This year, the famous Holy Light Ceremony took place in a near-empty church. The streets were bare and closed off with iron bars. An elderly woman at home in Bethlehem since February expressed how such a sight would never have been imaginable, regardless of how much her 88-year-old eyes had seen in a lifetime.

Aside from the fact that the holiest time of the year for Christians coincided with the most intensive lockdown restrictions, another factor added to their challenge, something which does not have clear parallels in the Jewish and Muslim traditions. According to Eastern Christianity, worship is incomplete without physically congregating and participating in the sacraments. Unlike in some Christian denominations, particularly in the West, worship services in the oldest Christian traditions can only be performed in a consecrated place by an ordained priest, culminating in the offering of the Eucharist. This means that praying at home or watching from a TV screen does not suffice. A denial of the sacraments could be interpreted as a severe interference in one’s right to worship.

So how did the oldest Church in the Holy Land strike a balance amid a region-wide lockdown?

A basic tenet of Christianity is that cooperating with governmental authorities to an extent that is reasonable is both a duty and helpful in matters of conflicting interest. In Jerusalem’s long and contentious history, this policy has helped to maintain the presence of the Orthodox Church for nearly 2,000 years. In the case of the coronavirus, the Heads of Churches issued several official statements that directed their followers to abide by the health and safety measures in place. At the same time, they met with local authorities and police in order to negotiate certain conditions that they deemed vital to their spiritual obligations. For example, rather than closing the Church of the Holy Sepulcher completely as initially mandated, they explained the need for minimal numbers of clergy to conduct services. In Jerusalem, priests held liturgies within the several Old City monasteries for a maximum of ten attendees at a time. In Bethlehem and surrounding towns, priests visited homes in order to offer the pre-sanctified Eucharist. According to one Beit Sahour resident, the local priest sent messages to his congregation encouraging them to follow guidelines but to reach out for any need.

Aside from the spiritual needs of the community, one of the most threatening realities for families was the sudden loss of income. The economic disparities that were already apparent in the region became more pronounced and tragic. The Patriarch of Jerusalem Theophilos III announced at the onset of the pandemic that all rent collection by the Church would be stopped for one year. As Israel’s largest non-governmental landowner, this provided significant relief, even though its own means of income had ceased. Thousands of food parcels and other aid were also distributed to families in need throughout the Patriarchate’s jurisdiction comprising Israel, the Palestinian Territories, and Jordan, which helped to quell general panic exacerbated by limits on movement and worship.

Perhaps one of the most overlooked elements of the Eastern Christian response to the pandemic is its philosophical explanation as to why such disasters occur in a world supposedly created by God. Several highly respected public figures have recently said that the Church is not a helpful participant in this conversation. The opposite effect can be observed in Jerusalem. The Church’s rhetoric has aided in a kind of collective psychological overcoming of the issue, at least at the present moment. Assad Mazawi, a Jerusalem-based attorney who deals with a spectrum of issues for the Christian community said that he saw a kind of transformation within himself and others. “The duality of the crisis and Great Lent, maybe they fit together. Here in the native land of Christianity, seeing the efforts of our churches at this hard time, we were forced to be humble as our God instructs. It forced us to go back to the origins of our faith,” he said. In its statements to the public the Church has encouraged a deeper respect for nature, invoked the arguments of climate-change activists, and promoted consideration of where humanity, as stewards of the earth, trespasses its limits, in terms of fossil fuel usage, corporate greed, and biological experimentation.

This combination of factors has provided some respite to the Christian community in the Holy Land, so deeply affected by the economic and religious implications of the coronavirus, and has in some ways also helped set the region on a course that does not pit religious worship against safety and security.

Note: This piece gives the views of the author(s), and not the position of the LSE Religion and Global Society blog, nor of the London School of Economics.

Clearly written and examining a hopeful response to our current situation. Thank you.

A fascinating read! Authoritative and clearly conveyed. Gives a real insight into the complex dynamics of the time and of the region.