Much of the debate over school improvement in the U.S. over the past two decades has focused on specific policy reforms. Using findings from new research, which examines how states govern education, Paul Manna argues that the amount of centralization in a state’s system can have an equally important role. He finds that states with more centralized political structures, which allow governors to appoint top education officials, had smaller achievement gaps. Those that were more administratively centralized by maintaining fewer school districts also had lower achievement gaps, but reduced achievement overall.

Much of the debate over school improvement in the U.S. over the past two decades has focused on specific policy reforms. Using findings from new research, which examines how states govern education, Paul Manna argues that the amount of centralization in a state’s system can have an equally important role. He finds that states with more centralized political structures, which allow governors to appoint top education officials, had smaller achievement gaps. Those that were more administratively centralized by maintaining fewer school districts also had lower achievement gaps, but reduced achievement overall.

Lively debates over how to improve American schools have flourished in the past two decades. Frequently, these discussions have focused on specific policy reforms while tending to ignore the broader issue of education governance. That imbalance is unfortunate.

At first glance, highlighting the difference between policy and governance may seem like an exercise in academic hair-splitting. Still, the distinction is useful because it focuses attention not only on policies themselves, but also on the actors and institutions that produce and implement those policies in the first place, something that researchers commonly call the “education governance system.” Policy and governance can contribute to the results that parents, politicians, and school officials desire, so attending to both should be part of any strategy to improve educational outcomes. In recent research, I have shown how the degree of centralization in state education governance is associated with both positive and negative outcomes in terms of overall student achievement and achievement gaps between student groups.

My study of governance and achievement focused on the fifty U.S. states and addressed the question: Are states with more centralized education governance systems more likely to have higher student achievement and lower achievement gaps between poor and non-poor students? This is an important question given the affection for local control of schools that dominates public opinion in the U.S. That popular view is in tension with other efforts, as embodied in the state standards movement that began in the 1980s and more recent federal policies, such as the No Child Left Behind Act and the Race to the Top Program, that have intensified the states’ roles as overseers of their K-12 systems of schooling.

Focusing on 2003 to 2009, my research examined two outcomes: overall levels of student achievement in reading and math for 4th and 8th graders, and gaps in achievement between economically disadvantaged students and their more advantaged peers in those same grades and subjects. Students were considered to be economically disadvantaged if they qualified for subsidized meals at school. These achievement results came from the federal National Assessment of Educational Progress test, which is administered every other year to representative samples of students in each state.

I attempted to account for state variation in overall achievement and achievement gaps by relating those results to the degree of political, administrative, and fiscal centralization in the education governance systems of the fifty states. Two measures captured political centralization: whether the governor of the state was empowered to appoint the state education chief, who is the head of the state education department, and whether the governor possessed power to appoint all members of the state school board, a type of legislative body with various responsibilities that typically include authority over academic standards and teacher licensing. Administrative centralization was measured using the number of school districts in a state with fewer districts being a sign of greater administrative centralization. School districts are units of government that operate schools in local communities, and their boundaries may or may not overlap other local entities, such as cities and counties. Finally, I measured fiscal centralization as the percent of revenues for elementary and secondary education that came from non-local sources, meaning the combination of state and federal funds. Higher fractions of revenues from non-local sources were evidence of greater centralization.

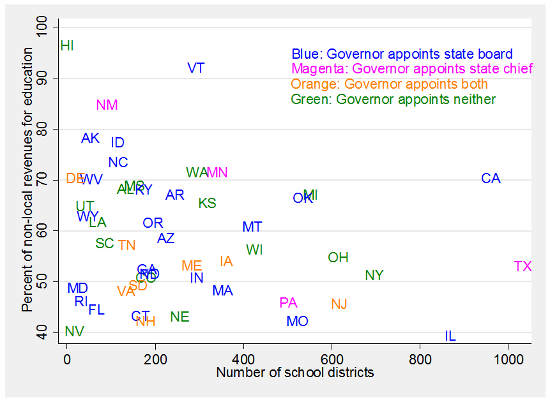

Figure 1 below presents illustrative data from 2008, a typical year in my time series, and reveals that states vary greatly across these measures of political, fiscal, and administrative centralization. In addition, the figure shows that centralization on one dimension is not necessarily associated with centralization on others. On the fiscal measure, the middle half of the overall distribution includes states falling between 49 and 68 percent of revenues from non-local sources. Regarding administrative centralization, the middle half of the distribution contains states possessing between 89 and 362 school districts. Finally, the color coded state labels indicate quite a spread in political centralization, with some states affording governors much latitude to make appointments to key education posts, while others limiting the governor’s authority in these areas.

Figure 1 – Education Governance in the U.S. States, 2008

Note: Governors were considered as having power to appoint the state board (states marked blue or orange) if the office of the governor was the sole entity that appointed state board members. States where governors appointed zero board members or some board members appear in green.

What about the relationship between centralization and achievement? On political centralization the results showed that states allowing governors to appoint the chief state school officer or appoint state education board members had smaller achievement gaps. However, there was no relationship between political centralization and overall achievement. Regarding administrative centralization an interesting tension emerged. More centralized states, meaning those with fewer school districts, had lower achievement gaps between students, which is evidence of more equitable outcomes. Yet more administrative centralization also was associated with lower overall achievement, suggesting that it can be challenging to simultaneously advance excellence and equity with greater administrative centralization. Finally, fiscal centralization was unrelated to student outcomes, both in terms of overall achievement and achievement gaps between students.

In all, my study reveals the virtue of examining student success through the lens of state education governance. Knowing that gubernatorial appointment powers and the number of school districts, but not the percent of nonlocal revenues, appear to be associated with student outcomes can provide a nice launching pad for future discussions and empirical studies that unpack the reasons why these associations might exist. In short, attending to matters of policy and governance both can provide paths forward as the United States attempts to improve educational opportunities and outcomes for all students.

This article is based on the paper “Centralized Governance and Student Outcomes: Excellence, Equity, and Academic Achievement in the U.S. States,” in the Policy Studies Journal.

Featured image credit: Larry Darling (Creative Commons BY NC)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/MoK4UR

_________________________________

Paul Manna – College of William & Mary

Paul Manna – College of William & Mary

Paul Manna is Associate Professor of Government and Public Policy at the College of William & Mary. He is the author of School’s In: Federalism and the National Education Agenda (Georgetown University Press, 2006), Collision Course: Federal Education Policy Meets State and Local Realities (CQ Press, 2011), and co-editor, with Patrick McGuinn, of Education Governance for the Twenty-First Century: Overcoming the Structural Barriers to School Reform (Brookings, 2013). His research on education governance has been supported by the Spencer Foundation.