Youth participation in American presidential elections has flat-lined since the 1970s, echoing similar trends in other Western democracies. But does this mean that young people have given up on politics? James Sloam argues that while young people have been driven away from voting due to a lack of political choice and the dysfunctional nature of politics, they are increasingly drawn to other forms of citizen activism. He writes that more young people are taking up petitions, boycotts and demonstrations than ever before, especially those with higher levels of education.

Youth participation in American presidential elections has flat-lined since the 1970s, echoing similar trends in other Western democracies. But does this mean that young people have given up on politics? James Sloam argues that while young people have been driven away from voting due to a lack of political choice and the dysfunctional nature of politics, they are increasingly drawn to other forms of citizen activism. He writes that more young people are taking up petitions, boycotts and demonstrations than ever before, especially those with higher levels of education.

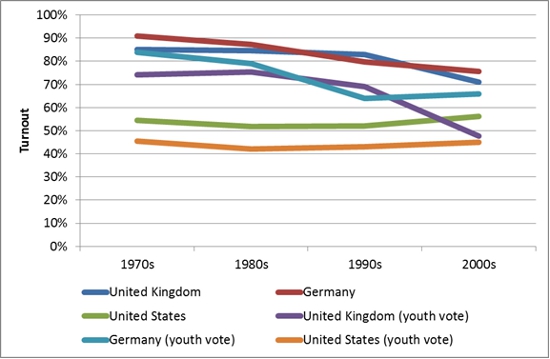

Many academics and political commentators have become concerned by the apparent lack of youth participation in American democracy. In the wake of Robert Putnam’s ‘Bowling Alone’ (2000), it became generally accepted that the United States was beset by a participatory crisis that undermined the very foundations of citizenship. Stephen Macedo and his colleagues in the Academy characterised these trends in ‘Democracy at Risk’ (2005).However, this negative narrative conceals more complex trends in civic and political engagement. First, it is important to point out that youth turnout in US presidential elections has plateaued (at a low level) rather than fallen since the 1970s (Figure 1, below). In other established democracies, youth turnout has fallen significantly or dramatically (in the case of the UK) from a much higher starting point.

Figure 1: Voter Turnout and the Youth Vote (18 to 24 year olds) in the US, the UK and Germany

Sources: American National Election Studies, British Election Study, German General Social Survey

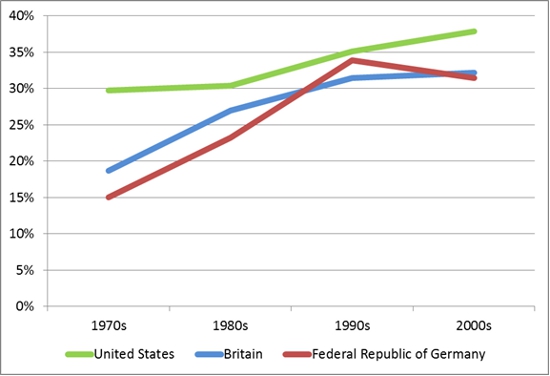

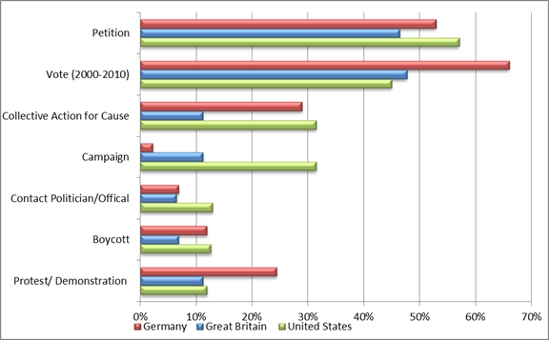

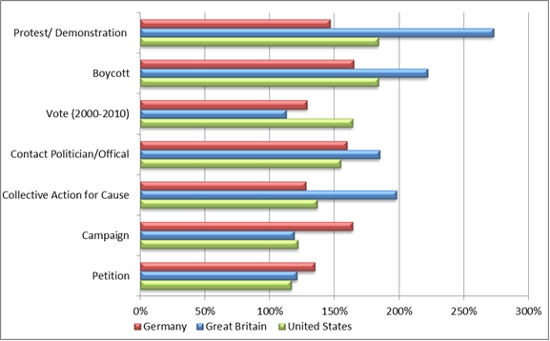

However, the bleak picture painted of a new generation indifferent to politics only offers a partial account of youth participation in United States. Pippa Norris, through her conceptualisation of a ‘Democratic Phoenix’ (2002), provided a counterpoint to this gloomy diagnosis – one in which young Americans were ‘reinventing political activism’ in their own image. Russell Dalton, in his book ‘The Good Citizen’ (2009), makes a similar point about young people’s politics, which he argues is increasingly populated by ‘engaged citizens’. By broadening traditional definitions of civic and political engagement, it became apparent that youth engagement was evolving to encompass new repertoires, agencies and arenas of participation: from consumer politics, to community campaigns, to international networks facilitated by online technology; from the ballot box, to the street, to the Internet and new social media; from political parties, to social movements and issues groups, to social networks. Figure 2 illustrates the increasing levels of citizen activism through petitions, boycotts and demonstrations since the 1970s. And, in many non-electoral forms of participation, young Americans outperform their peers in Britain and Germany (Figure 3).

Figure 2 –Average Participation in Petitions, Boycotts and Demonstrations in the US, Britain and Germany since the 1980s

Figure 3: Civic and Political Engagement of Young People (15-24 year olds) in the US, Britain and Germany

Sources: European Values Study/ World Values Survey, Comparative Study of Electoral Systems, national election studies.

Of course, youth participation in the United States is heavily structured by the political system and the socio-economic environment. Comparatively low levels of voting in presidential elections might be explained by lack of political choice and the dysfunctional nature of the US political system. Young Americans were enthused by the 2008 presidential campaign of candidate Obama. However, Obama’s promise of ‘change’ was not realised due, not least, to gridlock in Washington.

Nevertheless, young people in the United States have often sought to bring about change at local, city or state level through, for example, initiatives to improve schools or reduce crime in their local neighbourhoods, or to reduce the voting age in local and state elections. Otherwise, young Americans have increasingly channelled their political voice through personalised (non-institutionalised) networks into new social movements (what Lance Bennett and Alex Segerberg refer to as ‘The Logic of Connective Action’, 2013). Occupy was just the tip of the iceberg – one of a multitude of youth-inspired political projects.

But the rebirth and reimagining of political participation is not relevant for all groups of young Americans. They have been conditioned by the growing social inequalities in society. Sidney Verba and his colleagues, in their seminal book ‘Voice and Equality: Civic Voluntarism in American Politics’ (1995), identified social inequality as a key determinant of civic and political engagement. Since the 1990s, youth participation in America has (disturbingly) become less equal.

Putnam and Thomas Sander, in their 2010 article ‘Still Bowling Alone? The post-9/11 split’, wrote of the doubling of civic engagement amongst college students between 2001 and 2010. The Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement reported in 2011 that 59 percent of young Americans with less than a high school diploma could be categorized as “civically alienated” or “politically marginalized”, compared to 39 percent of those with a high school diploma and only 13.5 percent of those with a college degree. In the United States, voting rates are both relatively low and much more strongly linked to educational attainment than is the case in Britain or Germany (Figure 4). Education is also important in determining Americans’ participation in non-electoral forms of politics, but the domination of these activities by college-educated citizens is comparable to Germany and less than in Britain.

Figure 4 – Civic and Political Engagement of Citizens with College Degrees in the US, Britain and Germany as percentage of National Mean

Sources: European Values Study/ World Values Survey, Comparative Study of Electoral Systems, national election studies

The participation of young Americans in public life is encouraging in one sense – they are actively engaged in a wide spectrum of political activities. However, voter turnout in the United States is already heavily structured by citizens’ socioeconomic status and levels of educational attainment. This effect is only exacerbated by the emergence of alternative forms of participation, as highlighted in Schlozman, Verba and Brady’s ‘The Unheavenly Chorus:

Unequal Political Voice and the Broken Promise of American Democracy’ (2012). The problem of how to overcome these inequalities of participation poses some existential questions for American democracy. They relate directly to issues of social mobility and income inequality that featured strongly in the 2012 presidential race (largely thanks to the Occupy Movement).

These results pose further questions and suggest some interesting new avenues for research. How might it be possible to foster these emergent forms of civic and political engagement while at the same time ironing out social inequalities? How can better linkages be created between electoral politics and young people’s politics (the politics that young people already do)? For the present, young Americans will find ways to make a difference on the issues they care about in spite of the inertia of traditional political institutions.

This article is based on the paper ‘New Voice, Less Equal: The Civic and Political Engagement of Young People in the United States and Europe’ in Comparative Political Studies.

Featured image credit: Jordan Richmond (Creative Commons BY)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1pc2wA2

_________________________________

James Sloam – Royal Holloway, University of London

James Sloam – Royal Holloway, University of London

James Sloam is reader in politics and director of the Centre for European Politics and co-ordinator of the Youth Politics Unit at Royal Holloway, University of London. He is co-convenor of the PSA specialist group on young people’s politics (for details of our September conference follow this link). He has published widely in the area of youth politics in journals such as Parliamentary Affairs, West European Politics and Comparative Political Studies. Shorter pieces on youth participation and reengaging young people in democracy can be found on the Fabian Society and LSEEUROPP blogs and Political Insight magazine.