Common wisdom holds that lobbying and lobbyists influence government policy towards the preferences of the well-resourced. In new research, Tim LaPira which examines interests groups in the wake of the creation of the “homeland security” regime in 2002. He finds that the move to the new policy regime attracted new short term lobbying interests, while older, better established groups only shifted their focus to the new issue temporarily. In light of these findings, he argues that new government policies, such as “homeland security” help to create lobbying, not the other way around.

Common wisdom holds that lobbying and lobbyists influence government policy towards the preferences of the well-resourced. In new research, Tim LaPira which examines interests groups in the wake of the creation of the “homeland security” regime in 2002. He finds that the move to the new policy regime attracted new short term lobbying interests, while older, better established groups only shifted their focus to the new issue temporarily. In light of these findings, he argues that new government policies, such as “homeland security” help to create lobbying, not the other way around.

Conventional wisdom about lobbying influence is that money buys policy. Yet political scientists have for years found contradictory or inconclusive results when putting this idea to the test. For most interest groups money doesn’t work. For some selected rich folks’ money seems to work.

What is often assumed—yet rarely made explicit—by the money-buys-policy folk theory is that simply flashing money around or being a corporation can change what government does. In other words, the recipe for influence is to pump campaign cash into politicians’ coffers, buy up some well connected K Street lobbying contracts, then something, something, something and—voila—INFLUENCE! The assumption is simple: those interests outside government who have the resources and the wherewithal can cause government to do something that it otherwise would not do. In other words: special interests have power. As Silicon Valley has learned, it’s not so simple. The real world of politics is much more complex.

Actually, the causal direction likely goes the other way. Rather than special interests causing government to act, they respond to what the government is doing. The government sets the agenda, and organized interests react. Political scientists refer to this process as the “government demand” theory of interest groups. The political context matters at least as much as the amount of “influence” special interests pump into the political system. The evidence to support the government demand theory has typically observed government attention shifting from one issue to the next, and interest groups following their lead.

In recent research, I tested a variation of this theory that looked at how interest groups follow government attention over time. I analyzed lobbying disclosure reports to exploit a rare punctuation in policy equilibrium to test competing hypotheses about (a) existing interests shifting their attention to new sexy “Homeland Security” issues vs. (b) new interests setting up shop in Washington to exploit it. Homeland security was the perfect intervention in the otherwise stable interest group population. The whole purpose of the new policy domain was to coordinate otherwise disparate policies dealing with a variety of natural disasters and terrorist attacks that spanned many economic sectors and government agencies.

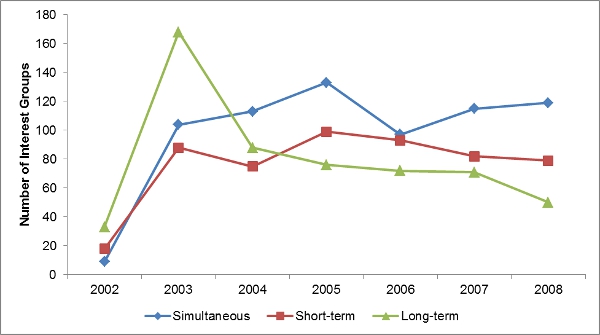

I find that the attempt to synthesize many agencies under the newly defined “homeland security” policy regime in the mid-2000’s did not uproot previously entrenched interests as intended. Rather, established interests retreated back to their primary domains of interest. Figure 1 shows the 1,782 unique interest groups that reported lobbying on “Homeland Security” through 2008, including “long-term” interests are those that had been registered to lobby before 1998 (when disclosure reports became available online). “Short-term” interests hired a lobbyist or opened a DC office between 1999-2001, so were not well established when homeland security was created. And, “simultaneous” groups established a presence in DC specifically to lobby on Homeland Security issues, obviously after September 11, 2001.

Figure 1 – Lobbying interests under “homeland security” police regime, 2002 – 2008

What’s surprising here? Interests that previously had no presence in Washington lobbied up for Homeland Security. Then stayed. But the old guard—groups that may have had a presence in DC dating back to World War II or before—only temporarily shifted to the new issue, then retreated back to their old ways to lobby on other issues.

In short, I show that there are very real, tangible consequences of creating a new “boundary-spanning policy regime:” entrenched interests retreat to their antecedent domains, but a whole new set of interest groups get drawn into the policy process. So, when the state’s role to protect life and property was redefined as “homeland security,” two concrete things happened in Washington: the new regime failed to resolve jurisdictional conflicts, but succeeded in attracting a whole new set of groups seeking largesse from government.

Homeland Security created more lobbying. Not the other way around.

Featured image credit: Thomas Hawk (Flickr, BY-NC-2.0)

This article is based on the paper ‘Lobbying after 9/11: Policy Regime Emergence and Interest Group Mobilization’ in the Policy Studies Journal.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1tOCfsV

_________________________________

Tim LaPira – James Madison University

Tim LaPira – James Madison University

Tim LaPira is associate professor of political science at James Madison University in Harrisonburg, VA. He earned his PhD in political science from Rutgers University in 2008. He has also worked as a legislative assistant to a member of Congress and as a researcher at OpenSecrets.org, where he was responsible for the Lobbying and Revolving Door databases. LaPira’s expertise is on Congress, interest groups, lobbying, and money in politics. He is currently writing a book on the revolving door between Capitol Hill and K Street with Herschel F. Thomas.