While efforts in the corporate world to promote gender diversity have been ongoing since the 1990s, the representation of women at higher corporate levels is still relatively poor – more than 83 percent of board directors are still male. In new research on women scientists in the oil and gas industry, Kristine Kilanski examines the effectiveness of corporate diversity programs. She finds that despite the good intentions of these programs, they can work to shift an organization’s focus away from the sources of gender inequality, and often do little to help women advance through the corporate ranks.

While efforts in the corporate world to promote gender diversity have been ongoing since the 1990s, the representation of women at higher corporate levels is still relatively poor – more than 83 percent of board directors are still male. In new research on women scientists in the oil and gas industry, Kristine Kilanski examines the effectiveness of corporate diversity programs. She finds that despite the good intentions of these programs, they can work to shift an organization’s focus away from the sources of gender inequality, and often do little to help women advance through the corporate ranks.

Corporations today proclaim a strong commitment to gender diversity. They publicize this commitment in their mission statements, job advertisements, recruitment materials, public relations, and personnel policies. Since the 1990s, a cottage industry of diversity consultants has developed to help companies become more diverse, advertising their services as a means to improve the corporate bottom-line and reduce potential legal liabilities. In response, most major corporations have instituted a variety of diversity management initiatives; some of the most popular of these include affinity groups, formal mentoring programs, diversity training, and targeted recruitment and promotion programs.

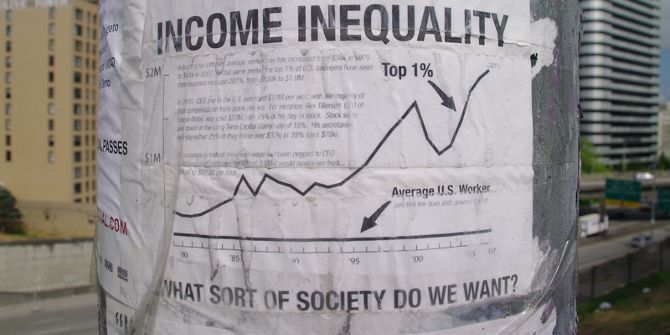

On the surface, corporate efforts to promote gender diversity seem promising. However, despite two decades of the corporate “diversity craze,” executive suites are still overwhelmingly male-dominated. For example, even though women now account for more than 50 percent of college graduates and roughly half the paid labor force, they comprise fewer than 17 percent of board directors and 15 percent of executive officers. In addition, most contemporary workplaces remain characterized by high levels of horizontal gender segregation, with women overrepresented in “feminized occupations” characterized by lower pay, prestige, and little room for advancement.

Organizational scholars are questioning the effectiveness of corporate diversity programs. Our research on women scientists in the oil & gas industry reveals important insights into the failure of these programs to increase equity and power for women in the workplace. We found that instead of helping to promote women workers’ interests, the corporate embrace of diversity has shifted organizational focus away from identifying and mitigating organizational sources of gender inequality. Replacing the discursive framework of “civil rights” once drawn upon by advocates for social justice, the diversity programs embraced by corporations obscure the continued salience of gender in the workplace. Under the banner of “valuing diversity,” corporations focus on identifying and celebrating any number of employee characteristics or personality quirks, rendered into depoliticized “differences” that they can foster through low- or no-cost interventions.

For example, it was typical for the employers we studied to sponsor affinity groups for employees with shared social characteristics, interests, and hobbies. Corporate list-servs and sponsored group activities can provide a social good to workers, opening up opportunities to form personally meaningful connections with other employees with whom they share common ground. However, a corporate-sponsored list-serv for parents does nothing to address the fact that mothers are offered less money than fathers and childless men and women for the same work, or that women with children often hit a “maternal wall” to advancement in their careers. Despite this, corporations tout these minor investments as evidence of their commitment to fostering a diverse work environment, and importantly, meeting the legal requirements of the Civil Rights Act and other worker-equality laws.

Other popular diversity management strategies do little to help women advance up the ranks in the corporate world. Many oil & gas companies now assign new employees formal mentors to help them learn the ropes of the organization and plan their career development. Formal mentors vary in quality, but we found that even the best mentors are limited in their ability to help women climb the corporate ranks. While mentors can advise women on how to navigate the particular issues that impact them in the workplace, they lack the power to remove the barriers (e.g., “the glass ceiling”) that women face. In fact, many of the most understanding and supportive mentors to women —other women— face the very same barriers to advancement encountered by their mentees.

Diversity training is by far the most popular form of diversity management utilized by corporations. We found that diversity training can backfire by promoting gender stereotypes and women’s subordination in the workplace. For example, one woman we interviewed drew on a corporate sponsored Myers-Briggs personality test to explain why she was assigned as an executive assistant to a man with whom she had shared a job title prior to a recent corporate merger. “I’m taking over those softer skills because I just do that well,” she told us. Other women told us that diversity training taught them that, because of gender differences in communication, men were natural “leaders” while women were “team players.”

Women scientists in the oil & gas industry are troubled by their underrepresentation in the industry and, especially, the dearth of women in management. However, when asked how they would like their companies to respond to these perceived inequities, they grow cautious. Although organizations that have targeted recruitment and promotion policies are more inclusive of women in management, women are wary of these particular policies. They worry about advocating for policies that, as they see it, would privilege gender over merit. The paradox is that these same women work in organizations in which men and qualities associated with masculinity are privileged. Without access to a civil rights discourse, however, it is difficult for women to demand remedies to systematic gender inequality.

Corporations’ commitment to “diversity” does not itself translate into more opportunities for women, and often, we found, reinforces gender discrimination. Only when corporations actively commit to identifying and breaking down gender barriers —such as when companies set specific equality goals, and hold leaders accountable to achieving them— do women experience gains in the workplace

This article is based on the paper “Corporate Diversity and Gender Inequality in the Oil and Gas Industry,” by Christine Williams, Kristine Kilanski, and Chandra Muller, in Work and Occupations.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of U.S.App– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1zfmTht

_________________________________

Kristine Kilanski – University of Texas at Austin

Kristine Kilanski – University of Texas at Austin

Kristine Kilanski is a PhD candidate and a Graduate Fellow of the Urban Ethnography Lab at the University of Texas at Austin.