May has been a pivotal month in the US presidential election; it has seen the continued success of Donald Trump in the Republican Party’s presidential primary, and his ascension to become the party’s likely presidential nominee. Walter Dean Burnham writes that Trump’s victory, and to an extent, the success of Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, have been part of another realignment of US politics, one which has left many in both parties completely at sea.

Republicans: Donald J. Trump, his April-May surge, and Victory

When Donald Trump entered the race for the Republican presidential nomination in the summer of 2015, he had many competitors. Even he, it seems, did not initially expect to win more than about 10 percent of the primary vote. So, evidently, did the GOP’s establishment, which has since failed to understand, or to cope with, the political environment. It has wholly lost control of the situation.

When Trump entered the race, his and their expectations were systematically refuted. He moved into a huge vacuum, which he increasingly filled – winning 20 percent in early contests, then 30 percent then 40 percent. Finally, in all contests in the Northeast, he won more than 50 percent (Pennsylvania, Maryland) and even more than 60 percent (New York, Delaware, Rhode Island, and Connecticut).

By the pivotal month of April 2016, all Trump’s opponents had quit the contest, except for Texas U.S. Senator Ted Cruz and Ohio governor John Kasich. At the end of of day, the latter only won his home state of Ohio and the borough of Manhattan in New York; and, statewide, never got out of the 20 percent range. As for Cruz, a supreme right-wing ideologue and, personally, the most hated member of the Senate, was unable to gain traction among republican primary voters outside the south and some mountain states except in Wisconsin.

Then came the vote in Indiana on May 3rd: Trump, 53 percent; Cruz, 34 percent; Kasich, 9 percent. The contest ended very abruptly when Cruz gave up his campaign (Kasich followed on May 4). The Republican National Committee asserted, on the evening of May 3, that Donald J. Trump had become “the presumptive nominee” of the GOP. The TV networks were to use the same words on May 4. The race was over! The establishment’s last-ditch effort to deny Trump the majority of delegates, at the July 18 convention (1237) seems, by all odds, to have collapsed in ruins. The coup de grâce, if any were still to be needed, will follow in California and New Jersey on June 7.

Democrats: Hilary Clinton is “Presumptive Nominee,” But….

Very early on, the party establishment rallied around a single candidate, former Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton. A kind of “coronation” was planned. Whether this was a wise choice will be ratified – or not – on November 8.

But, among the Democratic voters, the coronation was indefinitely postponed. Here the establishment had its way, but at a cost. For the eruption of a runaway electorate centered on a most unlikely claimant, Senator Bernie Sanders. Until last year, Sanders was a self-proclaimed socialist. Representing one of the smallest of states, Vermont, he threw his hat into the ring as a protest candidate. But he entered a void, paralleling that seen in the Republican Party, and he rapidly filled it. By early May Sanders had won in 19 states, capping this achievement with a “surprise” defeat of Clinton in Connecticut – polls, as so often, having predicting her to win in the Nutmeg State.

Associated with this feat was the most extreme age-gradient differential I have ever witnessed. Among those surveyed under 30, Sanders was preferred by fourth fifths of respondents, while Clinton’s majority was up to 2:1 among middle-aged and older voters. If Donald Trump’s chief slogan was/is “Make America Great Again,” so Sanders proclaimed “A Future We Can Believe In.” One could easily imagine another: “Hilary Clinton is Yesterday’s Candidate.” She, in turn, has to some extent tacked to the left in her campaigning, but suffers from other impediments too. In view of a widespread doubt about their prospects in the slow-growth era that seems on the horizon, young democratic white voters may well be seeking a pretty radical way out of the impasse in which many feel trapped.

At the same time, it is noteworthy that – very unlike Republican voters – Democrats (more than 70 percent) believe that the primary season has energized their party. As a “movement” candidate, Sanders intends to do what he can to place his agenda at the conventions on the party platform. Nor is there any sign of the secession of major party elites from Clinton – in sharp contrast to Donald J. Trump as the GOP’s “presumptive” nominee. And she is very solidly grounded in support among African Americans, Latinos and other vital segments of her base.

Still, who can have any certainty about the November outcome? One of the prime features of critical realignments is that established politicians are completely at sea in the midst of such events. Some examples:

In 1854-1855: Massachusetts: State Senator Charles Francis Adams stated: “There has been no revolution so complete since the organization of the government” (p. 137). A Whig journalist: “I no more suspected the impending result [Know-Nothing landslide in the election of Nov. 1854] than I looked for an earthquake which would level the State House and reduce Faneuil Hall to a heap of ruins”.

The Democratic Convention of 1896: Incumbent President Grover Cleveland was a leader of the Gold Democrats. Against them was an uprising of the Populists and Silver Democrats. These, as representatives of the southern and western colonies, rose against the “Gold Bugs” of the northeastern metros. This was in the context of one of the three most severe depressions in American economic history. Very early on it was clear to contemporaries that the insurgents would control the party convention. William Whitney of New York, a leader of the gold wing, opined that he felt like a man in the French Revolution on his way to the guillotine.

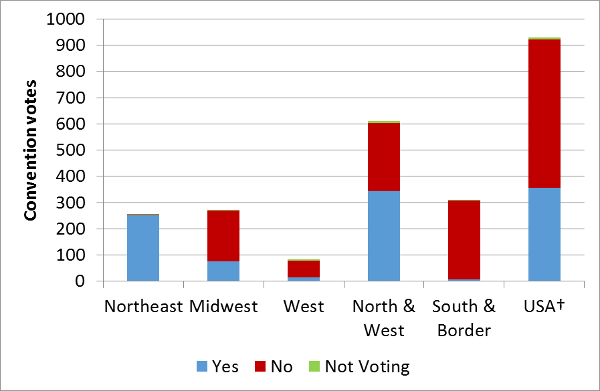

After the dust settled, for the only time in history, an incumbent president was repudiated by his own party’s convention, as Figure 1 shows. The pattern by state was one of extreme sectionalism, as were the election results in 1896 and for long afterwards.

Figure 1 – Regional Vote on Commending the Cleveland Administration, Democratic Convention, 1896

Note: †Final numbers include Votes from territories

The long-term effect of this critical realignment was to produce a Republican hegemony in the more economically developed parts of the US. And that lasted until the collapse of the private sector of the economy, and the pivotal election of 1932 which saw the election of FDR. In the meantime, the city beat the countryside, and the metropolitan areas beat the US’ internal colonies.

2016 (so far): The uproar and disorientation within the leadership cadres of the Republican Party since the victory of Donald Trump are notorious matters of record in every day’s newspapers and TV outlets. One example is Senator John McCain (R –AZ). The Senator seeks re-election to a 6th term. This time he faces serious opposition (Rep. Ann Kirkpatrick), and the possible undertow from an anti-Trump surge among Latinos, who constitute about 1/3 of Arizona’s electorate.

So, what to do? Run a separate campaign on one’s own record of 30 years in the Senate. McCain’s reaction: “Mr. McCain said he was unsure how Ms. Kirkpatrick’s campaign strategy linking him to Mr. Trump would be received in Arizona. ‘I really don’t know… Things continue to evolve at blinding speed.” Precisely.

Reports of the “death” of the GOP are grossly exaggerated. It has experienced worse strains, notably in the 1912 election. It is too deeply embedded in the white electorate at various levels (US House, state governors, state legislatures) to disappear, as did the Whigs of ancient memory.

Are we passing through a critical-realignment sequence? We certainly are, though of a very special type. Watch this space…

Featured image credit: Elvert Barnes (Flickr, CC-BY-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1U1tw1c

______________________

Walter Dean Burnham – University of Texas at Austin

Walter Dean Burnham – University of Texas at Austin

Walter Dean Burnham is Professor Emeritus at the Department of Government at the University of Texas at Austin. Professor Burnham is best known for his work on the dynamics of American politics (particularly electoral politics). His chief areas of concentration have been on the causes, characteristics and consequences of critical realignments in American history, and the modern-day decay of partisan linkages between rulers and ruled. Much of his recent work has also concentrated on the “turnout problem” and its relationship to other elements of change in American politics. Before coming to Texas in 1988, he was Ruth and Arthur Sloan Professor of Political Science at Massachusetts Institute of Technology.