The way that state and federal government are elected in the US has changed very little in the past two centuries. Yet, the entrenched two-party system has led to increasing calls for electoral reform. One reform, used in many other countries, is proportional representation. Jack Santucci writes that some US cities were actually able to institute proportional representation before 1950 when the losing party and ruling party defectors teamed up. He cautions, however, that proportional representation does have its trade-offs.

The way that state and federal government are elected in the US has changed very little in the past two centuries. Yet, the entrenched two-party system has led to increasing calls for electoral reform. One reform, used in many other countries, is proportional representation. Jack Santucci writes that some US cities were actually able to institute proportional representation before 1950 when the losing party and ruling party defectors teamed up. He cautions, however, that proportional representation does have its trade-offs.

As the 2016 election has shown us, voting rules are a barrier to third parties gaining power in government. For now, voters have to choose the least of two evils when only one person can win. Unhappy voters in both major parties face the same hurdle. What if your party nominates candidates you don’t find acceptable? You have four options: vote for its candidate, vote for the other party’s candidate, don’t vote at all, or work to change your party leadership. People in this situation sometimes turn to proportional representation (PR) elections as a potential fix. If a party or faction gets ten percent of votes in PR, it gets ten percent of legislative seats.

PR elections are possible, but the price is working with enemies. Changing the rules takes more power than a small group has on its own. Say you need a majority to switch to PR. Say the ruling party controls a majority. How do you build a majority of support for PR? You need a diverse coalition of groups. Part of this must come from the current majority. The rest has to come from losing parties.

Americans have turned to PR before. Historians say it took fights between party machines and well-meaning reformers. Later writers said the reformers’ motives were suspect. But all of this language is loaded. What happens if we study the players as we find them?

Pro-PR coalitions in American history

In new research, I looked at 24 PR adoptions in American cities, 1915-48, then some cities where PR failed. Ruling-party defectors made common cause with losing parties in at least 15 of these cases. Change tended to fail without this type of alliance. Consider Worcester, Massachusetts, which adopted PR in 1947. Democrats controlled city government, but many in the party were unhappy. Republicans were also unhappy since their party was not in power. The groups teamed up and imposed PR in local elections that year.

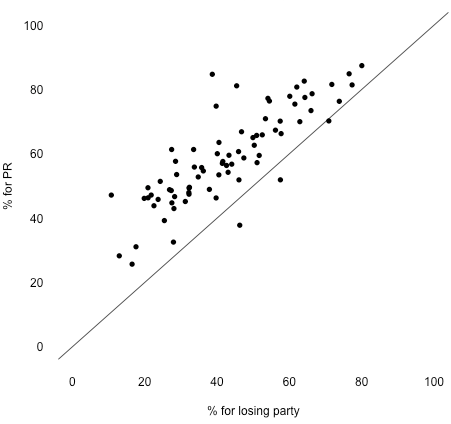

Results of the PR referendum reflect this constellation of interests. Dots in Figure 1 below represent voting precincts. The x-axis gives the percentage of voters who supported the Republican mayoral candidate. The y-axis gives the percentage who voted for PR. The diagonal line is where dots would cluster if only Republican supporters voted for PR. Since most of the dots are above this line, it looks like many Democratic supporters also voted for PR. A rigorous analysis tells us that roughly 40 percent of Democratic voters joined the Republicans in supporting PR.

Figure 1 – Losing party and ruling party defectors team up in Worcester, Mass., 1947

Once PR was in place in Worcester, the Democratic defectors formed a legislative party.

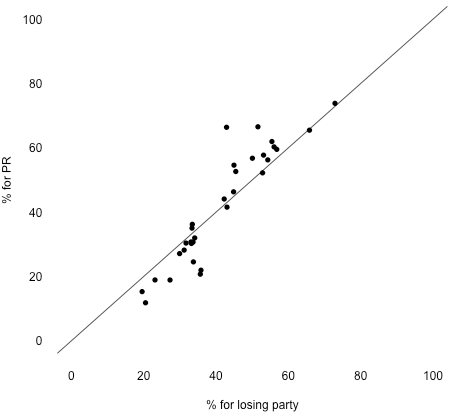

Now consider Waterbury, Connecticut, another diverse, industrial city 90 miles from Worcester. Proportional representation failed there in 1939 because the ruling Democrats averted a split. Why? The leader of would-be defectors was holding out for a mayoral nomination. Figure 2 shows what happens when defectors and out-parties don’t cooperate. Waterbury Republicans were mostly alone in voting for PR.

Figure 2 – Ruling-party defectors abandon losing party in Waterbury, Conn, 1939.

Cincinnati is another case. Unhappy Republicans wanted to oust their party leadership, but once again, they could not impose change alone. They turned to the out-party Democrats, and PR passed in 1924.

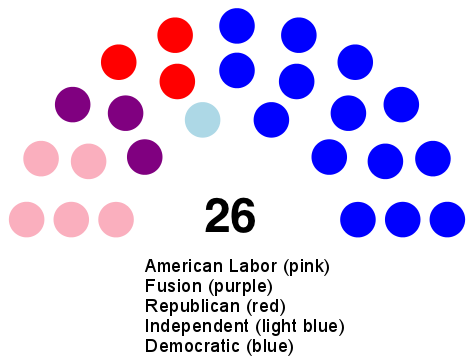

How general are these patterns? I looked all city charter reforms in the 100 largest cities between 1900 and 1950. I took the vote for governor in the respective county as a proxy for partisan balance. PR adoptions only happened with roughly two-party balance. I argue this is because two-party cities are more likely to produce PR coalitions than cities with hegemonic parties. Multi-party cities can also produce PR coalitions, but this was rare. In 1936, New York City Republicans teamed up with the American Labor Party and Tammany-Hall defectors. New Yorkers used PR for ten years.

Figure 3 – Result of New York City Council elections, November 1937

Peace with parties is a precondition for change

We sometimes hear that PR is a tool for getting rid of parties. That’s how the national PR lobby first talked about it. At the time, supporters of PR were in an alliance with backers of “direct legislation,” which we know today as letting voters make the laws. Here is how they talked about parties in 1896:

In this country, each party has a long platform containing many issues. We have to support measures which we do not approve for the sake of measures which we want.

The anti-party attitude lasted for nearly two decades. Then in 1914, a group on the board of the PR League demanded a split from “direct legislation” backers. Perhaps not by coincidence, Ashtabula, Ohio became the first PR city one year later.

Change means accepting some risks

We also hear that everybody wins with PR. Every salient group elects its deputies, and these make deals acceptable to all. The truth is that PR also has winners and losers. Majorities still need to form. The difference in PR is that this happens after elections.

Big, non-PR parties try to serve many groups at once. Conflicting interests within a party make this service imperfect. Splitting these parties to win PR can reshuffle the distribution of benefits, and that is PR’s appeal. Historians identify female candidates, labor unions, and civil rights leaders as faring especially well.

But even when these groups pushed for PR, they did not always get power. Some earned too few votes to win seats. Others did not join ruling coalitions, were kept out of them, or had too few seats to be pivotal.

Why do we not see PR adoptions today? One reason is the structure of advocacy. As in the late 1890s and early 1900s, advocates and their likely allies do not agree on the form of PR to promote. Second, Democrats now dominate most medium-to-large cities. Third, unions, many racial and ethnic minorities, and the feminist movement have secured what appear to be durable levels of bargaining power in the Democratic coalition. This means there is less need today to collude with the other party to thwart conservative interests within one’s own party. None of these conditions is necessarily permanent.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Party Splits, Not Progressives The Origins of Proportional Representation in American Local Government’ in American Politics Research.

Featured image credit: Peter Rukavina (Flickr, CC-NC-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2h7zGUs

_________________________________

Jack Santucci – Georgetown University

Jack Santucci – Georgetown University

Jack Santucci is a Ph.D. Candidate studying American politics at Georgetown University.

2 Comments