At the beginning of October, the Trump administration published the US’ first new National Strategy for Counterterrorism in seven years. Jonny Hall writes that while the new Strategy goes beyond its predecessors in some respects, it is also littered with oddities, inconsistencies and contradictions with previous US counterterrorism efforts. He argues that overall, the new strategy is fairly conventional in its approach – and as such is essentially divorced from Trump’s day to day counterterrorism rhetoric.

At the beginning of October, the Trump administration published the US’ first new National Strategy for Counterterrorism in seven years. Jonny Hall writes that while the new Strategy goes beyond its predecessors in some respects, it is also littered with oddities, inconsistencies and contradictions with previous US counterterrorism efforts. He argues that overall, the new strategy is fairly conventional in its approach – and as such is essentially divorced from Trump’s day to day counterterrorism rhetoric.

In his 2016 election campaign, then-candidate Trump emphasized the threat of terrorism, and counterterrorism is now a significant part of US foreign policy. Despite this focus, the administration’s National Strategy for Counterterrorism (the first since 2011) was released in October without much attention. This document has six points of interest which I think are worth discussing (see also Joshua Geltzer’s and Daniel Byman’s articles at The Atlantic Brookings covering topics such as working with partners.)

‘We Remain at War’

The new document’s executive summary has the subheading, “We Remain a Nation at War”. This is largely a semantic point given that the Barack Obama administration was very much fighting a war against terrorism (just without labelling it as such), but it is nonetheless significant that it is pronounced at the very beginning of the strategy document. On one hand, Byman argues that the strategy’s authors should have avoided this claim, given that it overemphasizes the terrorist threat, whilst also obscuring the successes since 2001 in preventing large-scale terrorist attacks on American shores.

While these points are correct, this advice not only obscures the impact of lethal counterterrorist actions abroad (what are drone strikes if they are not war?), but also helps to normalize counterterrorist campaigns away the possibility of challenge from the public, in an inverse of rhetorical strategies such as the “War on Drugs” or “War on Poverty”. Indeed, the quiet escalation of airstrikes and drone strikes during the Trump administration speaks exactly to these risks. The merits of fighting counterterrorism as a war are as questionable as they were when George W. Bush first declared a “War on Terror”, but at least this national counterterrorism strategy is honest in this regard.

Identifying the Terrorist Threat

Three things stand out in this regard. Firstly, the new strategy identifies the same primary terrorist threat to the United States, but instead of referring to al-Qaeda and its specific affiliates, the document uses the much broader term ‘radical Islamist terrorist groups’. This discursive shift away from both Obama and Bush was well-detailed at the time and certainly deserves attention, but it is also interesting as the phrase seemed to have gone out of fashion – Trump has only tweeted the phrase ‘radical Islam’ once since December 2017.

Secondly and relatedly, the strategy continually dances around the threat of terrorism ‘not motivated by a radical Islamist ideology’ through a series of vague references such as ‘[t]errorists motivated by other forms of extremism also use violence to threaten the homeland and challenge United States interests.’ At its two most specific moments, the strategy somewhat oddly lists two European groups – the Nordic Resistance Movement and the National Action Group – as dangerous extremist groups, before later putting ‘racially motivated extremism’ in the same list as ‘animal rights’ and ‘environmental’ extremism. Ross Glover’s 2002 statement that ‘clearly we are not looking for white terrorists when we speak of the war on terrorism’ seems truer than ever in this strategy.

The final notable change is unsurprising, as Iran is mentioned much more prominently in this strategy (on ten occasions) than its predecessor (on one occasion). This certainly fits with the administration’s recent rhetoric and actions, with National Security Advisor John Bolton labelling Iran the long-time “central banker of international terrorism” just the day before the counterterrorism strategy’s release.

“President Donald J. Trump with Senior Military Leaders” by The White House is Public Domain.

Dealing with the Terrorist Threat

Understandably, the new document attempts to go beyond the 2011 strategy in highlighting the importance of social media in both terrorism and counterterrorism. Merely in terms of diagnosis of the scale of the task at hand, the strategy has lots of agreeable soundbites. For example, the strategy states that despite its territorial setbacks ‘ISIS maintains a sophisticated and durable media and online presence that allows it to encourage and enable sympathizers worldwide to conduct dozens of attacks within target countries’, and that ‘[u]nless we counter terrorist radicalization and recruitment, we will be fighting a never-ending battle against terrorism’. However, much like most strategy documents of this kind, the prescription is frustratingly diffuse. The extent to which the Trump administration (and the administrations that follow) will be successful in this area remains to be seen.

Oddities and Inconsistencies

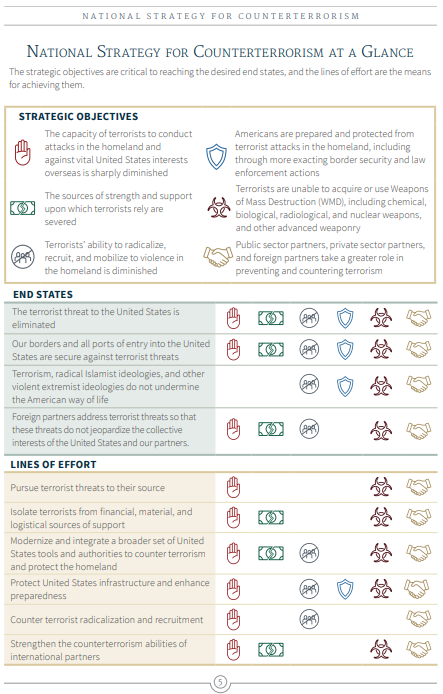

One part of the strategy that should not go unremarked upon is the bizarre childlike theme introduced in the ‘at a glance’ section and then used throughout the document. This theme uses six clip art figures to represent ‘strategic objectives’, as if trying to dumb down the strategy for the lay person to be able to understand. Not only this, but the theme is employed poorly and incoherently with a series of gaping errors.

Figure 1 – National Strategy for Counterterrorism infographic

On the matter of inconsistency more broadly, the strategy flickers between identifying realistic goals (‘we will not dilute our counterterrorism efforts by attempting to be everywhere all the time, trying to eradicate all threats’) and more ambitious ones (‘we will … prevail against terrorism’, ‘we will defeat our enemies, just as we have in … previous wars’). What is particularly puzzling here is how the first quote feels like an explicit critique of the original “War on Terror”, whilst the following quotes are straight from the George W. Bush administration’s textbook. On this final point, the return of some rhetorical tropes from this era seems particularly alarming, and hardly a ‘relief’ as Joshua Geltzer described the strategy as a whole. For example, the strategy declares that since 9/11 ‘we have learned that winning the war on terrorism requires our country to aggressively pursue terrorists’, which is not necessarily the obvious lesson to be taken from 17 years of counterterrorism since 2001.

Whose counterterrorism strategy?

As with all national counterterrorism strategies, this document has a foreword written and signed by the President. There is a noticeable tension in this foreword which has also characterized Trump’s rhetoric in the White House, namely his desire to declare the Obama era as a dystopian existence, whilst simultaneously claiming that the Trump administration has already solved these problems despite their magnitude. This tension is especially apparent given that the counterterrorism strategy is meant to be planning for future events, whilst Trump is eager to claim credit (and has previously lamented the lack of gratitude) for ‘prevailing against the terrorists aiming to harm us and our interests’.

The final point relates to a similar question I have explored with regards to the National Security Strategy, and whether we should take any notice of the fairly conventional strategy when Trump’s speech presenting it was so different. In that case, my answer was positive, as the speech and the strategy represented the differing views within the administration. With no meaningful announcement speech, what struck me this time was quite simply the irrelevance of Trump to this counterterrorism strategy; the few attempts to include Trump’s rhetoric were not only ill-fitting but were from planned speeches where Trump occasionally tempers his outrageousness. On the whole though, most of Trump’s rhetoric – such as his rallies – is bewildering, erratic, incoherent gobbledygook.

And yet, time and again during the Trump presidency (myself included), foreign policy commentators have imposed wisdom, coherency, and relevance on Trump that quite frankly doesn’t exist. This leads to a unit of analysis problem; this counterterrorism strategy reflects current administration policy, but equally Trump’s personal opinions are almost completely absent from it as well. I do not mean to suggest that Trump’s personal opinions are irrelevant everywhere as this is demonstrably false, but in more technical areas such as counterterrorism, even labelling this strategy ‘Trump’s counterterrorism strategy’ is a fundamental error that clouds our own understanding of national security policies.

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/2PRwgDr

About the author

Jonny Hall – LSE International Relations

Jonny Hall – LSE International Relations

Jonny Hall is a PhD Candidate in International Relations at the LSE. His research interests lie in American foreign policy, specifically counterterrorism Discourse in the Donald Trump era and the value of presidential rhetoric in this area in historical comparison.