In new research, Justin de Benedictis-Kessner and Michael Hankinson find that financial self-interest means that Democrats and low-income Republicans are generally more open to paying more taxes to fund opioid treatment programs. But why, then is there a shortage of opioid treatment clinics in many American communities? In their survey research, the authors also determine that both Republicans and Democrats do not support siting a clinic close to them in their community.

In new research, Justin de Benedictis-Kessner and Michael Hankinson find that financial self-interest means that Democrats and low-income Republicans are generally more open to paying more taxes to fund opioid treatment programs. But why, then is there a shortage of opioid treatment clinics in many American communities? In their survey research, the authors also determine that both Republicans and Democrats do not support siting a clinic close to them in their community.

Each day more than 130 people in the US die from an opioid overdose, making it the leading cause of death for Americans under 50. Nevertheless, policymakers at the federal, state, and local level have struggled to combat this epidemic. Too little funding has been appropriated for substance use disorders and too few clinics exist to administer such treatment, especially in rural areas. Why has the policy response to the opioid epidemic fallen so short of its magnitude?

Our new research identifies several barriers to both funding and implementing new opioid treatment policy. First, people are sensitive to how much they’ll pay in taxes to fund public health responses. However, this financial self-interest is not only less prevalent among Democrats, but also spurs lower-income Republicans to join Democrats in supporting treatment funding. Yet despite this bipartisan coalition, people across the political spectrum are opposed to the siting of new clinics in their community. And because local governments control where clinics are built, that opposition will prevent even a widely supported public health response from reaching full implementation.

To unpack the politics of opioids, we surveyed a nationally-representative sample of 2,000 people. We first asked respondents to express their level of support for a $100 million state bill funding opioid treatment programs. We then used a survey experiment to see how sensitive respondents are to the location of new methadone treatment clinics in their community – the actual implementation of treatment policy.

Respondents saw one of two scenarios for the funding proposal that allocate the $100m bill’s financial burden differently. In the first scenario, the financial burden was “income-based” or “redistributive.” Under this policy, respondents with a household income greater than their state’s median income would pay $55, whereas those with a household income below the state’s median would pay only $5. This policy design matches most social policies where those with the greatest ability to pay shoulder the most costs. We expected that financial self-interest would cause higher-income individuals to support this policy less than would lower-income individuals.

“Methadone clinic protest sign” by RJ is licensed under CC BY SA 2.0.

In a second scenario, we asked respondents for their support of an “overdose rate-based” or “needs-based” funding model for a policy. Under this policy, respondents living in areas with a higher opioid overdose rates would pay more ($55) than those in areas with a lower overdose rate ($5). is policy design is the same as the status quo, wherein local governments with higher rates of overdoses have been forced to fund local treatment programs, often taking on debt in the process. Again, based on financial self-interest, we expected people living in areas with higher overdose rates to support this policy less than those in areas with lower overdose rates.

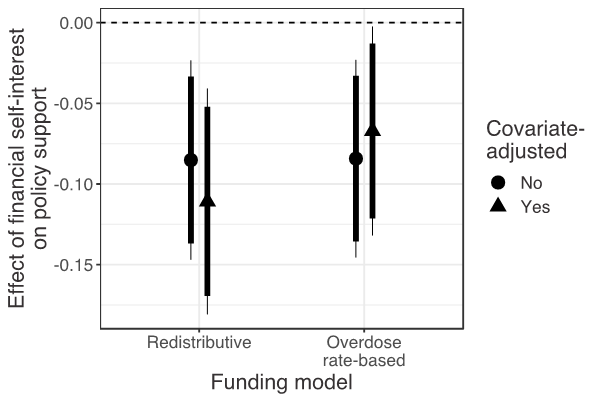

As Figure 1 shows, our expectations were met. Respondents with higher household incomes supported the redistributive proposal at lower rates than those with lower incomes. And respondents who lived in areas with higher overdose rates supported the overdose rate-based proposal less than those who lived in areas with lower overdose rates. In both cases, people supported funding proposals that would involve them paying less at greater rates than funding proposals that would involve them paying more – indicating that financial self-interest can shape public opinion in this issue area.

Figure 1 – Support for funding scenarios for opioid treatment

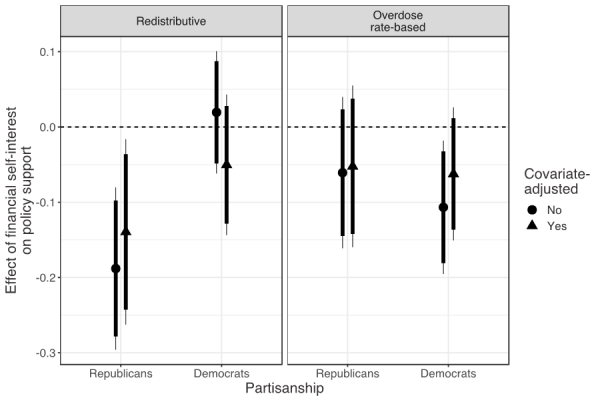

But while financial self-interest was important, political partisanship also shaped support for the treatment policies. In fact, we find that the gap between Republicans and Democrats in support for both funding proposals is twice the size of the effect of self-interest. However, financial self-interest worked differently depending on the partisanship of the people in our survey, as we show in Figure 2. Both lower- and higher-income Democrats equally supported the redistributive funding policy, indicating little influence of financial self-interest. In contrast, higher-income Republicans starkly opposed the funding, whereas support among lower-income Republicans was much closer to that of Democrats than their high-income Republican counterparts. In other words, financial self-interest points to a potential bipartisan coalition of support that savvy policymakers could leverage for passing policies to halt the number of opioid overdoses.

Figure 2 – Support for funding scenarios for opioid treatment by party affiliation

But funding is only half the battle. We also assessed obstacles to policy implementation by using an experiment to measure the role of geography by asking respondents for their support of a proposal to build an opioid treatment clinic in their community. To understand how sensitive they were to location, we randomly assigned respondents to evaluate a proposal that described this clinic as either near their home (¼ mile, or a 5-minute walk) or far from their home (2 miles, or a 40-minute walk). This varied the acuity of respondents’ local concern, given people often fear that clinics will undermine public safety and decrease nearby property values.

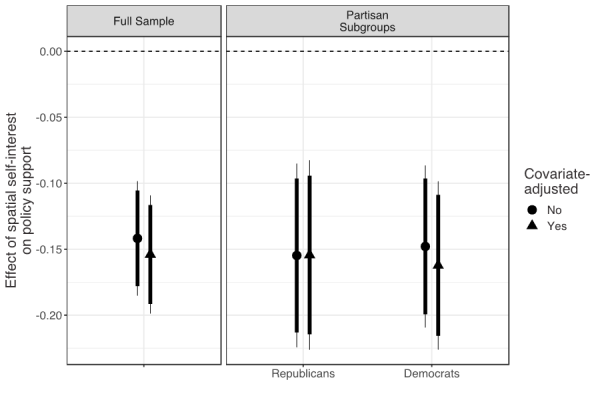

The results from our experiment, shown in Figure 3, indicate that spatial self-interest exerts a powerful influence on people’s opinions. Respondents evaluating a proposal for a treatment clinic near their home were much less supportive of the policy than those who evaluated a proposal for a clinic far from their home. This spatial sensitivity was similarly sized among both Democrats and Republicans. Despite support for funding to confront the opioid crisis, local self-interest still led respondents to oppose the infrastructure needed to actually implement those policies.

Figure 3 – Support for funding scenarios for opioid treatment by party affiliation and clinic location

Our results point to two implications for public policy. First, policymakers should leverage financial self-interest in designing opioid treatment policy. We have identified a potential coalition of support among Democrats and lower-income Republicans in favor of a progressively funded opioid treatment bill. Second, policymakers should be aware of the local obstacles to implementation. Not only are NIMBY (‘Not In My Backyard’) attitudes towards treatment clinics strong, they are bipartisan. Strong support for public funding will not directly translate to new clinics, even in liberal areas. Furthermore, wealthier, whiter, older voters are more likely to organize in local politics. Policymakers must resist the pressure from these politically active communities to concentrate treatment clinics in low-income and minority neighborhoods that are less politically vocal.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Concentrated Burdens: How Self-Interest and Partisanship Shape Opinion on Opioid Treatment Policy’ in American Political Science Review.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2MqfT27

Justin de Benedictis-Kessner – Boston University

Justin de Benedictis-Kessner – Boston University

Justin de Benedictis-Kessner is Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at Boston University. His research covers American politics, with a focus on political behavior, public policy, local politics, elections, and experimental and quantitative methodology.

Michael Hankinson – Baruch College, City University of New York

Michael Hankinson – Baruch College, City University of New York

Michael Hankinson is Assistant Professor of Political Science at Baruch College, City University of New York. His research looks at how institutional spatial scale affects political behavior to undermine democratic representation.