While the Democratic Party was successful in retaking the White House in the 2020 elections, it was unable to gain a majority in the US Senate. Ryan Williamson and Jamie Carson find that Senate elections have become largely nationalized: there was little variation on average between the electoral success of Democratic Senate candidates and that of Joe Biden in the states they were contesting.

While the Democratic Party was successful in retaking the White House in the 2020 elections, it was unable to gain a majority in the US Senate. Ryan Williamson and Jamie Carson find that Senate elections have become largely nationalized: there was little variation on average between the electoral success of Democratic Senate candidates and that of Joe Biden in the states they were contesting.

Despite losing the presidency and a number of toss-up Senate races leading up to the election, Republicans fared well in the 2020 Senate elections, winning 50 seats outright. Many believed the Democratic Party would unseat a handful of vulnerable Republican senators on their way to regaining control of the chamber. So what ultimately happened? In a word, nationalization.

Recent elections have been increasingly defined by partisanship at the expense of individual candidate characteristics. Voters now are more likely to base their decisions on which party they prefer to see in power nationally instead of which candidate would best serve their individual needs at the state or local level.

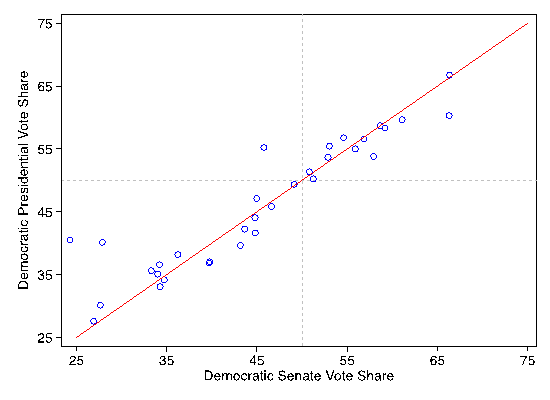

As such, many voters are reluctant to split their tickets (voting for one party in the presidential election and another in the Senate election). The 2016 Senate elections marked the first time in US history in which there were no “purple states.” Every state won by Hillary Clinton saw the Democratic Senate candidate succeed, and every state carried by Donald Trump saw the Republican Senate candidate win. The 2020 Senate elections nearly repeated this feat. As shown in Figure 1, only one state (Maine) saw candidates from different parties win the statewide races. Otherwise, the parties either won both the presidential vote and the senate vote or lost both of them. Neither of Georgia’s senate elections were decided on election night and will proceed to a runoff in January. As such, even if the Republican candidates do ultimately prevail in a state won by Biden, their wins are qualitatively different than those that took place with the presidential race at the top of the ticket. Therefore, we exclude them from the discussion moving forward.

Figure 1 – 2020 election Democratic Senate vs presidential vote share

This is not to say that individual candidates cannot have an independent effect on the election outcome even with nationalization. In fact, in such a highly nationalized environment, candidate characteristics can carry even more importance in determining the outcome. Finding a candidate who can mobilize their base without similarly bringing out the opposition is a must in the current political environment. Furthermore, candidates will also need to convince at least 3-5 percent of voters to split their ticket in defiance of the national parties’ strategies. Even then, that may not be enough to change the outcome of a highly polarized election.

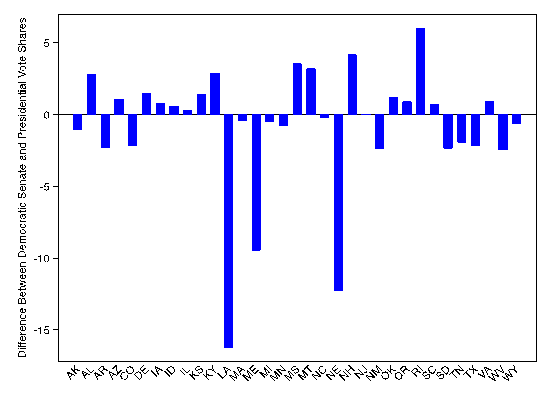

To illustrate this, we look at the difference between the percentage of the vote won by the Democratic Senate candidate against the vote won by President-Elect Joe Biden within each state (Figure 2). Positive values show candidates who ran ahead of Biden, and negative values represent states where the Senate candidate underperformed relative to Biden.

Figure 2 – 2020 Democratic Senate candidates’ performance relative to Joe Biden

The average difference in this figure is less than one percentage point— 0.77. Indeed, despite some noticeable outliers, in 26 of the 33 races (78 percent) these figures were within three percentage points of each other.

“Election Day 2020” by Phil Roeder is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Senate candidates tended to track Joe Biden’s result in their states

The candidacy of Doug Jones in Alabama is particularly illustrative on this point. Jones was an incumbent senator with a record of bipartisanship and a desire to serve his state rather than his party. He was an experienced politician with a wealth of campaign resources. His opponent, Tommy Tuberville, had no political experience, many fewer resources, and was an ardent partisan. His campaign declined multiple invitations to debate Jones and refused to answer questions from all but a small number of conservative media outlets.

Working in Tuberville’s favor, however, was the strong partisan leanings of Alabama. Despite the experience and resource disparities, Tuberville won handily with over 60 percent of the vote. He campaigned on being a loyal supporter of Donald Trump in a state where the president was still a popular figure. This proved sufficient to propel him to victory.

Doug Jones was arguably the best candidate the Alabama Democratic Party could have fielded in 2020, and he ran an aggressive and impressive campaign. As such, he was able to outperform Biden by about three percentage points, but that was simply not enough for him to retain his seat in a state where Donald Trump carried 62.5 percent of the vote.

Diverse constituencies mean diverse responses are needed

This finding has important implications for current debates about the direction of the Democratic Party. Many moderate members have decried progressive policies and their messaging as obstacles to their own reelection bids. Meanwhile, progressives have argued that their moderate counterparts would have greater electoral success if they adopted more liberal positions. Similar arguments have been made by their counterparts in the House of Representatives (including by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY)).

Our results here suggest otherwise. In short, with such diverse constituencies and demands across the country, candidates will need to adopt specific, tailored personal brands in order to keep their Senate seats or flip those held by the other party. Necessarily, that means moderates will be electorally rewarded for being moderate and progressives will be reward for being progressive.

The onus is then on party leadership to devise a legislative and electoral strategy that satisfies the demands of both flanks of the party. That task becomes increasingly difficult when two factions of a party seek to advance their respective agendas in Congress, a fact that Republicans know all too well from the past decade that Democrats will likely be contending with for the foreseeable future.

This has tremendous consequences for the Georgia runoff elections. Instead of picking between the Republican and Democratic candidates on the ballot, voters will be thinking about the ultimate composition of the Senate. Indeed, many Democratic groups have argued that these races are crucial in the fight against Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell. On the other side, prominent Republican figures have argued that maintaining Republican control of the Senate is the last line of defense against the growth of radical leftist policies and socialism. Former Ambassador to the United Nations, Nikki Haley, starkly illustrated this dynamic when she tweeted that a vote for the Democratic candidates in the Georgia is a vote to make Bernie Sanders Chairman of the powerful Committee on Budget and included the hashtag “Say No to Bernie.”

Not only will we expect voters to be thinking about which party they most want in control of the Senate, we also know they are unlikely to split their tickets—making two Republican wins or two Democratic wins more likely than any other outcome. Both races are currently in a statistical tie and are shaping up to be about as close as the recent presidential election. With that, expect to see Republicans especially mobilized in light of their loss of the presidency. We should also expect to see enormous sums of money flow into the state given recent fundraising trends, as well as near nonstop mobilization efforts on behalf of each party’s respective candidates.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3olz4uc

About the authors

Ryan Williamson – Auburn University

Ryan Williamson – Auburn University

Ryan Williamson is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at Auburn University. He received his PhD from the University of Georgia, and previously worked on Capitol Hill as a member of the American Political Science Association’s Congressional Fellowship Program. His interests include Congress and Legislative Procedure, Congressional Elections, Institutional Development, the US Presidency, and Research Design and Methods.

Jamie L. Carson – University of Georgia

Jamie L. Carson – University of Georgia

Jamie Carson is the UGA Athletic Association Professor of Public and International Affairs II in the Department of Political Science at The University of Georgia. His primary research interests are in American politics and political institutions, with an emphasis on representation and strategic political behavior. Most of his current research focuses on congressional politics and elections, American political development, and separation of powers.