In Underdogs: Social Deviance and Queer Theory, Heather Love explores how queer theory was shaped by the Cold War-era world of deviance research. Presenting a careful, close reading of deviance studies, this book invites queer theorists to reconsider their intellectual heritage; how the field of queer theory will make meaning of these connections remains to be seen, writes Dani Slabaugh.

Underdogs: Social Deviance and Queer Theory. Heather Love. University of Chicago Press. 2021.

In Underdogs, Heather Love invites the still-adolescent field of queer theory and the Cold War-era world of deviance studies to a proverbial family therapy session, urging queer theorists to first acknowledge and then reconsider the contributions of their ostracised intellectual forebearers. Love’s case is not an easy task. The tension between these two fields is seemingly fundamental, and queer theory’s rejection of its intellectual parentage is an understandable reaction to deviance theorists’ methods, framing and aims.

In Underdogs, Heather Love invites the still-adolescent field of queer theory and the Cold War-era world of deviance studies to a proverbial family therapy session, urging queer theorists to first acknowledge and then reconsider the contributions of their ostracised intellectual forebearers. Love’s case is not an easy task. The tension between these two fields is seemingly fundamental, and queer theory’s rejection of its intellectual parentage is an understandable reaction to deviance theorists’ methods, framing and aims.

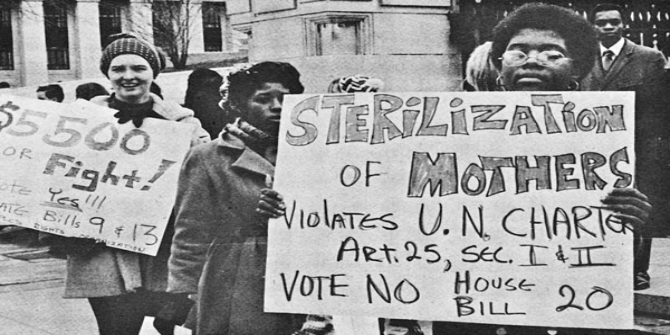

Deviance research emerged in the 1950s and 1960s as the study of supposed ‘problem populations’: drug addicts, homosexuals, drag queens, circus performers and others who lived outside of the ‘Leave it to Beaver’ values and lifestyle that dominated in the post-war era. These theorists observed and examined the lives of LGBTQ people, frequently without their knowledge, in an era when to be outed as such often resulted in dire threats to personal safety, social standing and job security, if not actual jail time.

Despite these ever-looming risks for its LGBTQ research subjects, deviance research was rooted in the ideals of objectivity and neutrality: the researcher’s role was to document the phenomena of LGBTQ individuals and the seemingly ‘peculiar’ lives of their community. Deviance researchers had no horse in the race, beyond their opportunity to make a mark on their chosen field. Critique of these shortcomings is implicit within queer theory – an unapologetically activist field that rejects the precepts and epistemology of the social sciences as fundamentally dehumanising.

Queer theory emerged decades later in the midst of the devastation wrought by HIV/AIDs and the subsequent political action demanding research and medical care led by ACT UP! and radical queer political activists committed to social transformation. In the intervening decades a movement had sprouted from the energy and agency of LGBTQ people across the country, from the Compton Cafeteria and Stonewall anti-police brutality riots in 1966 and 1969 respectively to the irreverent camp subculture distributed via mass media in the comically grotesque films of Divine and John Waters.

In this context, the field of queer theory seized and reconfigured the researcher’s tools to produce work by and for LGBTQ people. These theorists posited that society at large and its constraints were the real social problem, rather than problematising the marginalised individuals living outside strict cis and heteronormative social scripts. Since its inception in the early 1990s, the field of queer studies remains among the more activist, transformation-oriented and liberation-minded academic disciplines, going so far as to critique its own institutionalisation and question the role of the expert theorist. In short, queer theory rejects – on the surface – everything about deviance studies from its epistemological framework to its ivory tower positionality.

Underdogs suggests that while deviance studies has been disavowed in the quiet manner of academics, namely through under-citation, early queer theorists were influenced by the frameworks put forth in deviance research. What’s more, Love argues that these frameworks made meaningful contributions and may have played a significant part in queer theory’s successful integration into the academic world.

Image Credit: Photo by Markus Spiske on Unsplash

Love makes her argument by resituating deviance theorists in the context of Cold War ideology, McCarthyism and modernist academic culture. This context provides a vantage point from which she points to their various attempts to subvert, shift or otherwise undermine stigmatising and dehumanising narratives. In each theoretical example, Love makes no apologies for deviance theorists – a group who are generally suspect on moral and ethical grounds by today’s standards (and for some, by the standards of their own time: Laud Humphrey’s 1970s observational study of anonymous gay sex, Tearoom Trade, being an example of unethical research used in graduate research methods courses across the nation).

However, Love suggests that queer theorists are well served to read between the lines when approaching deviance studies, contextualising this work both within the constraints placed on Cold War sociologists whose professional self-preservation required them to be seen as objective and impartial, and the contributions these theorists have made to the more political, anti-authoritarian, anti-normative and even anti-academic field of queer theory that emerged decades later.

Love begins the book detailing the connections and ideological lineage that links theorists like Erving Goffman and his 1963 work, Stigma, with Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s later publication of ‘Queer Performativity‘ in 1993. The chapter begins by tracing Goffman’s citation in ‘Queer Performativity’, something Love takes as a critical revelation of the influences and context of Sedgwick’s work.

From this initial connection, Love launches into a close contextual reading of Goffman’s Stigma. She includes analysis not only of his work, but also the career context, notes from his students regarding his epistemological framework and his curious mandate that, upon his death, his personal archives, unpublished notes, manuscripts and correspondences be sealed to prevent posthumous speculation or revelations that would challenge the self-image he projected throughout his career.

Goffman was adamant that he was not an activist academic, nor did he care about the fate of his research subjects other than that they made for interesting research and led to publication within the field. Despite this callous approach, Goffman’s contribution to queer theory remains a useful one, Love argues. His work reframed LGBTQ individuals’ marginalisation as socially constructed rather than a natural consequence of their assumed ‘unnatural’ desires. With Goffman drawing comparisons across stigmatised and marginalised populations to make his case for the social construction of stigma, Love argues that he prefigures the coalitional big tent politics of queer theory and activism. Lastly, she argues that his emphasis on micro-sociology and aspects of identity as performance have made significant contributions not only to the work of Sedgwick, but also Judith Butler’s theories in Gender Trouble (1990), just three years prior to ‘Queer Performativity’.

Underdogs presents a thorough argument for queer theorists to understand the way their problematic forebearers have left indelible marks on the field. What to do with this collective intellectual self-knowledge is an open question. Love provides no prescription or recommendations, beyond collective self-reflection. Should the field of queer theory interrogate these inheritances? Should it pay homage through citation, lifting up research and theories shot through with dehumanising paradigms, an alienating research gaze and, in some cases, absent or somewhat abhorrent ethical standards? In light of these newly illuminated connections, what does queer theory owe deviance studies?

Perhaps the intellectual connection that Love so carefully unearths in Underdogs is a sign that without the deviance studies research of the Cold War era, queer studies departments would not exist today. Or perhaps it merely shows that early queer theorists began their intellectual work as all academics do, by surveying existing literature. Is queer theory a natural outgrowth of deviance studies, or would this intellectual tradition have emerged regardless as the LGBTQ community found its collective voice while fighting back against police brutality at Compton Cafeteria and Stonewall, marching in the streets and ‘dying-in’ at St Patrick’s Cathedral for the 1989 ‘Stop the Church’ protest? Love does not speculate here. Underdogs presents a careful, close reading of deviance studies, and invites theorists and scholars to reconsider their intellectual heritage. How the field of queer theory will make meaning of those connections remains to be seen.

- This review first appeared at LSE Review of Books.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3w0tB2t

About the reviewer

Dani Slabaugh – University of Colorado, Denver

Dani Slabaugh, MLA (she/they) is a PhD student in the Geography Planning and Design program at the University of Colorado, Denver. Their interests and passions revolve around non-speculative forms of land tenure, social movements, and climate justice. She roots her work in feminist, anti-racist and anti-colonial frameworks, engaging in research in order to contribute towards a more just, resilient, and thriving world. (my website is here: https://danimarieportfolio.wordpress.com/)