In principle, governments are elected to be responsive to the needs and opinions of the people they serve. But are governments that are too responsive to public opinion then less able to promote the wellbeing of their societies? In new research using data from the US states which quantifies the relationship between opinion and policy, Patrick Flavin finds that there appears to be no discernible pattern, with more government responsiveness linked to better outcomes for some areas and worse for others. There is little evidence, he writes, that listening to the public leads to less desirable societal outcomes as measured by metrics like crime rates, economic performance, and educational attainment.

In principle, governments are elected to be responsive to the needs and opinions of the people they serve. But are governments that are too responsive to public opinion then less able to promote the wellbeing of their societies? In new research using data from the US states which quantifies the relationship between opinion and policy, Patrick Flavin finds that there appears to be no discernible pattern, with more government responsiveness linked to better outcomes for some areas and worse for others. There is little evidence, he writes, that listening to the public leads to less desirable societal outcomes as measured by metrics like crime rates, economic performance, and educational attainment.

A government that responds to its citizens’ political opinions and governs effectively by advancing well-being are two of the essential features of a functioning democracy. From the time of America’s Founding and the subsequent Constitutional Convention of 1787, there have been concerns about a tradeoff between policy responsiveness and government effectiveness. The framers discussed the dangers of mob rule and how best to channel popular passions through elected representatives to avoid chaos from a political philosophy framework, but this debate also presents a question we can answer through research: are governments that are too responsive to public opinion less able able to effectively promote societal well-being and the common good?

This question is still relevant today as elected officials who cater to public opinion may advocate for overspending or be unable to make difficult political choices that could ultimately promote a more effective government and better outcomes. Moreover, this potential trade-off is of particular importance for new and emerging democracies as they make key decisions about election laws and institutional design that shape how closely (or not) elected officials are to the constituents they represent.

The link between political representation and wellbeing outcomes

To date, no empirical study has directly evaluated the possible linkage between the quality of political representation and societal wellbeing outcomes. To investigate this question, I use data from US states over several decades. In a new book, Devin Caughey and Christopher Warshaw create annual measures of public opinion and policy liberalism for both economic and social issues in the states for 1935-2020.

Using an analysis that quantifies the relationship between opinion and policy, I find that (as expected) over time states with more liberal publics are represented by state governments that implement more liberal public policies and that this holds true for both economic and social issues. Importantly, some data points (each a single state-year, example: Minnesota-1982) are close to the regression line (indicating a closer correspondence between opinion and policy) while others are a little or even a lot further away from the line. The distance from the line is my measure of policy responsiveness to public opinion – the further from the line, the less responsive state policy is to public opinion.

Photo by Edwin Andrade on Unsplash

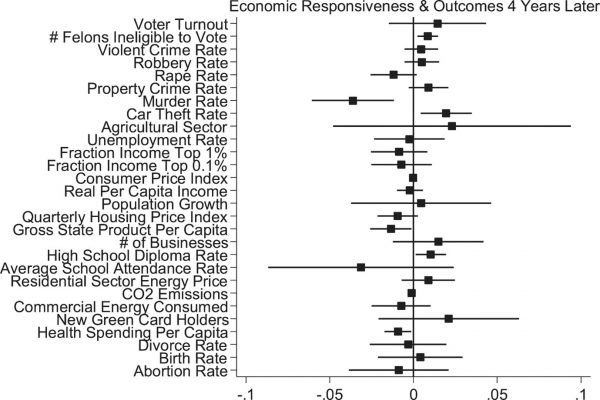

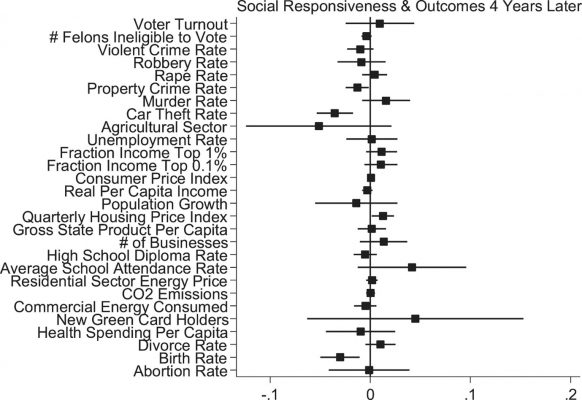

Using this measure of responsiveness for each state-year over time, I then turn to assessing its relationship with government effectiveness. Specifically, I draw on recent work by Adam Dynes and John Holbein that uses data from the Correlates of State Policy Project Database to examine 28 separate outcomes that capture states’ economic (example: unemployment rate), health/family (divorce rate), civic (voter turnout), criminal (violent crime rate), educational (high school graduation rate), and environmental (CO2 emissions) well-being. These outcome data are available for different timespans, with the longest going back to 1962 and the shortest to 1991.

I then evaluated the relationship between social and economic policy responsiveness and government effectiveness in the US states over time and find little evidence of a tradeoff. As Figures 1 and 2 show, when there is a relationship between the two, it is inconsistent and equally likely to be positive rather than negative – more responsiveness is linked to better outcomes for some areas and worse for others and there appears to be no discernable pattern.

Figure 1 – Economic responsiveness and outcomes

Figure 2 – Social responsiveness and outcomes

State political conditions and policy responsiveness

Using the same method of analysis to the above, I also examined the effects on social and economic policy responsiveness of certain political conditions within US states: whether a state has a ballot initiative process (direct democracy) or not, whether it imposes legislative term limits, or has united or divided government. My analysis, again, shows that there is a weak and inconsistent effect for each of the three factors on the relationship between policy responsiveness and government effectiveness

From a real-world perspective, these findings have important implications for our understanding of American democracy because they suggest that elected officials can seek to incorporate public opinion into policy decisions without sacrificing government effectiveness. Put simply, there is little evidence to suggest that heeding the public leads to less desirable societal outcomes as measured by metrics like crime rates, economic performance, and educational attainment.

- This article is based on the paper, “Is There a Tradeoff Between Policy Responsiveness and Government Effectiveness? Evidence From the American States” in American Politics Research.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3BgO7yi