Many Republicans believe that Joe Biden was not the winner of the 2020 presidential election, and that the contest was in some way “rigged” against former president Donald Trump. In new survey research using data from before and after the 2020 election, Sam Whitt, Alixandra B. Yanus, Mark Setzler, Brian McDonald, John Graeber, Gordon Ballingrud, and Martin Kifer find that Republicans’ satisfaction with democracy declined following the vote. They write that this declining satisfaction is linked to falling perceptions of the quality of elections – including doubts that elections are “free and fair” – and the news media.

Anyone who has watched the 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup can appreciate the thrill of victory and the agony of defeat in many fans’ reactions to their team winning or losing a game. When they are on the losing side, even the most passionate fans are willing to acknowledge when their team has been outplayed. Their distress and frustration are generally directed at weak defense, laggardly play, or—the classic scapegoat—bad refereeing. Observers might find it more remarkable, however, if members of the losing team, and their fans, directed their anguish directly at the game itself and the rules by which it is played.

Such negative reactions toward the fundamental, foundational rules of the game are commonplace in American politics today. In new research using a panel survey of the US 2020 election, we find that partisan Republicans emerged from the election—won by Democratic President Joe Biden—much less satisfied with the way democracy works, the quality of elections in the United States, and the news media who cover politics. How concerned should we be about this finding?

The “partisan gap” in satisfaction with democracy following elections

On one hand, the emergence of a “partisan gap” in satisfaction with democracy after contentious elections can be described as somewhat routine. In many studies of public opinion, partisan winners tend to emerge from elections with reaffirmed satisfaction with how democracy works, while partisan losers report rising dissatisfaction with democracy. Many scholars have sought explanations for these post-election gaps in democratic satisfaction. For example, we know that the gap tends to be worse in majoritarian or “winner-take-all” electoral systems, which are especially punitive toward losers because even a marginal loss is complete in terms of political representation. As a result, countries with presidential systems tend to also have greater partisan gaps than parliamentary democracies. Extreme ideological division, narrow margins of victory, and polarizing media coverage also contribute to the widening of the gap. In the US 2020 election, many of these contributing factors emerged, creating conditions for a wide gap in partisan satisfaction.

Our panel survey captured this gap. Conducted between October 27 and November 1, 2020, before the election and between November 10 and 23, 2020 after the election, we inquired about satisfaction with democracy among a randomly selected online sample. Approximately 500 Americans completed both the pre- and post-election surveys. Using panel data means that any changes in attitudes from before to after the survey cannot be spuriously attributed to “apples vs. oranges” comparisons. Attitudes may change, but the people who expressed them remain the same.

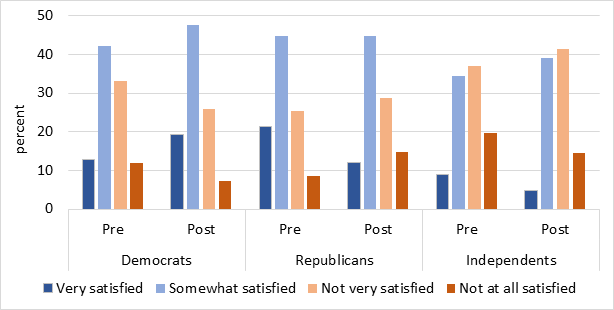

We asked panel participants, “On the whole, are you very satisfied, somewhat satisfied, not very satisfied, or not at all satisfied with the quality of democracy in the United States?” Response options ranged from not at all satisfied to very satisfied. Figure 1 indicates the percentage of responses (out of 504 total) to each of four response categories before and after the 2020 election. We separate respondents by their pre-election indication of partisanship as Democrats, Republicans, and Independents.

Figure 1 – Satisfaction with Democracy Before and After the US 2020 Election (Democrats, Republicans, and Independents)

Who is dissatisfied with democracy following an election?

Most partisan Democrats and Republicans are either very or somewhat satisfied with democracy both before and after the election. In contrast, most Independents are not very or not at all satisfied with democracy. While partisans often receive disproportionate attention during election coverage, a significant proportion of Americans do not identify with either major party. Our panel sample consisted of 41.5 percent Democrats, 29.8 percent Republicans, and 24.4 percent Independents. One could argue that for all the attention surrounding partisan changes in attitudes toward democracy, perhaps the more critical concern is a gap in satisfaction among Independents relative to partisans, a topic we hope to explore in future research.

“Stop The Steal, November 14, 2020 St. Pa” (CC BY 2.0) by Chad Davis.

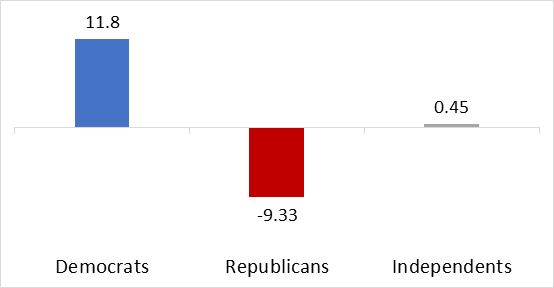

On the other hand, there is a clear change in satisfaction with democracy among partisan Democrats relative to Republicans after the 2020 election. Figure 2 takes the difference in the combined scores for very satisfied and somewhat satisfied respondents from after the election compared to before the election to calculate the partisan gap – the change in satisfaction with democracy among Democrats, Republicans, and Independents after the election. Democrats’ satisfaction with democracy increased by nearly 12 percent while Republicans’ satisfaction declined by 9 percent, an overall shift of 21 percent between partisan groups. Independents, in contrast, showed little change in satisfaction, which remained consistently lower at 43.9 percent compared to partisan Democrats (66.8 percent) or Republicans (56.7 percent) after the election.

Figure 2 – Percent Change in Satisfaction with Democracy After the Election (Democrats, Republicans, and Independents)

Republicans are losing confidence in the media and the electoral process

What explains the sudden shift in democratic satisfaction among partisan Americans? Our research explores this question in greater detail, comparing perspectives about rising concerns about economic well-being among partisan losers as well as psychological explanations of ‘affective polarization’, where losers exhibit rising fear and anxiety about what might happen once the winners, who are not part of their political in-group, take power. These explanations, however, are not very effective at predicting changes in satisfaction. Instead, our research finds that declining satisfaction with the quality of elections and the news media as well as rising doubts about whether elections in America are “free and fair” were the strongest predictors of declines in satisfaction with democracy among Republicans, relative to Democrats and Independents. When voters’ shifting perceptions of the media and doubts about the integrity of US elections are considered, the partisan gap between Democrat and Republican democratic satisfaction disappears in regression models.

If Republicans are losing confidence in the electoral process, then there is reason to worry that the partisan gap we observed after the 2020 election is more than something “routine” to American politics. The 2020 election outcome was ultimately marred by violence as partisan supporters of Donald Trump stormed the US Capitol on January 6, 2021, to overturn the election’s outcome. Many Republicans continue to deny the outcome of the 2020 election and refuse to see the process itself as legitimate.

If the American women’s national team were to fall in the World Cup this month, we hope the team and their fans will inspire everyone to be good sports about it. We could use more role models like that in our politics. The US 2024 election cycle is already underway, and it is unclear if the losing team, whoever they might be, will exit the field gracefully or that faith in the game will remain intact.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Explaining Partisan Gaps in Satisfaction with Democracy after Contentious Elections: Evidence from a US 2020 Election Panel Survey’ in PS: Political Science & Politics.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/44ViZBh