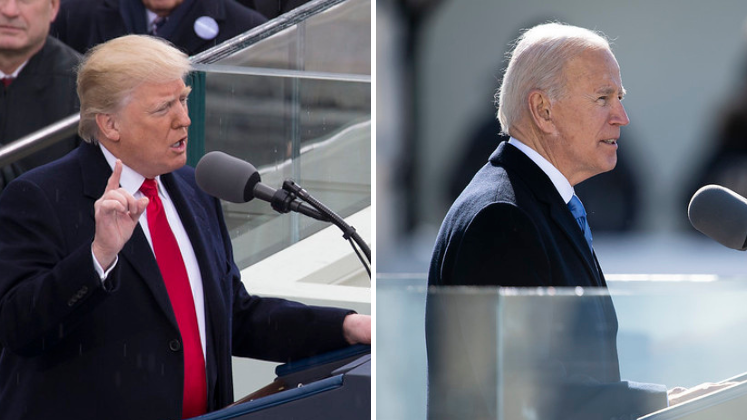

In just over a year, on January 20th, 2025, the next president of the United States will give their Inaugural Address on the steps of the US Capitol building in Washington DC. Jennifer Mercieca looks at what a new president’s rhetoric during their Inaugural Addresses can tell us about how they intend to govern. A close reading of former President Trump and President Joe Biden’s inaugural speeches in 2017 and 2021 show that Trump’s does not see the president’s role as protecting democracy, but to protect the nation’s border, while Biden sees that upholding democratic principles and constitutional limits is the president’s primary duty.

In just over a year, on January 20th, 2025, the next president of the United States will give their Inaugural Address on the steps of the US Capitol building in Washington DC. Jennifer Mercieca looks at what a new president’s rhetoric during their Inaugural Addresses can tell us about how they intend to govern. A close reading of former President Trump and President Joe Biden’s inaugural speeches in 2017 and 2021 show that Trump’s does not see the president’s role as protecting democracy, but to protect the nation’s border, while Biden sees that upholding democratic principles and constitutional limits is the president’s primary duty.

- This article is part of ‘The 2024 Elections’ series curated by Peter Finn (Kingston University). Ahead of the 2024 election, this series is exploring US elections at the state and national level. If you are interested in contributing to the series, contact Peter Finn (p.finn@kingston.ac.uk).

If both Joe Biden and Donald Trump are nominated by their parties, it will be the first time two former presidents have competed for re-election since 1912 when Theodore Roosevelt came out of retirement to challenge incumbent William Howard Taft and newcomer Woodrow Wilson. That election centered on policy debates over tariffs, worker protections, and corporate regulations. The 2024 election is less about policy issues and more about whether democracy will survive in America.

Or at least that’s how Biden has defined this moment in American history. He’s framed the election as another “time for choosing”—with the choice in 2024 between democracy and autocracy. Trump has accepted Biden’s framing, claiming at once that he would be a dictator only on “day one” and that Biden is “the true threat to democracy.”

It’s commonplace to quip that politicians “campaign in poetry” and “govern in prose”—that they use flowery and exaggerated language on the campaign trail but govern dispassionately and moderately. If that’s true, then how can we make sense of whether either Biden or Trump poses a real threat to the nation and democratic stability—is it just more hyperbolic campaign poetry or is the threat to democracy real?

Presidential Inaugural Addresses

A politician’s campaign poetry gives way to their governing prose in their Inaugural Address. Whether Biden or Trump (or, someone else) wins the presidency, when the next president swears the oath of office one year from now on January 20, 2025, they will use their Inaugural Address to articulate their view of political power and American values.

When we examine Trump and Biden’s Inaugural Addresses we see one president who sees his role as protecting the border and another who sees his role as protecting democracy and the Constitution.

Certainly there is a lot of soaring “poetry” in Inaugural Addresses, they are ceremonial occasions after all, but according to scholars Karlyn Kohrs Campbell and Kathleen Hall Jamieson, there is also a lot of meaningful political work done with them. As they wrote in 1985, typically, an Inaugural Address does four things: it “(1) unifies the audience by reconstituting its members as ‘the people,’ who can witness and ratify the ceremony; (2) rehearses communal values drawn from the past; (3) sets forth the political principles that will guide the new administration; and (4) demonstrates through enactment that the president appreciates the requirements and limitations of executive functions.”

Inaugural Addresses tell us who we and the nation are, what American values guide us, set presidential expectations, and assure us that the new president understands the obligations of the office. Most presidents use their Inaugural Address to celebrate American democracy and the Constitution—Biden did, but Trump did not.

The People and the Nation

When we look at Trump and Biden’s and Inaugural Addresses, we see stark differences in how they describe the nation and the American people.

In 2017— in the middle of an historic period of economic expansion, but after years of unpopular foreign wars and rising opioid addiction—Trump saw a nation of “disrepair and decay” filled with “forgotten men and women” who wallow in “American carnage.” As president, Trump vowed to protect the nation through isolationism, which he promised would lead to “great prosperity and strength.”

In 2021—just after the January 6th insurrection, and during the height of the COVID-19 global pandemic and resulting economic downturn—Biden saw “a great Nation” filled with “good people” who were being tested by an “historic moment of crisis and challenge.” As president, Biden vowed to unite the nation through living up to its values, which he promised would “make America, once again, the leading force for good in the world.”

American Values

When we look at Trump and Biden’s Inaugural Addresses, we see stark differences in what it means for America to be “great.”

Trump’s view of American Exceptionalism—American “greatness”—is America winning. Trump vowed that his presidency would usher in a new era of winning, “America will start winning again, winning like never before. We will bring back our jobs. We will bring back our borders. We will bring back our wealth. And we will bring back our dreams.”

Biden’s view of American Exceptionalism—American “greatness”—is America living up to its democratic values and promise. Biden vowed that his presidency would mark another moment in the long history of America living up to its values, “Through the Civil War, the Great Depression, World War, 9/11, through struggle, sacrifice, and setbacks, our ‘better angels’ have always prevailed…Together, we shall write an American story of hope, not fear; of unity, not division; of light, not darkness. A story of decency and dignity, love and healing, greatness and goodness.”

Presidential Expectations

When we look at Trump and Biden’s Inaugural Addresses, we see stark differences in what they thought their victories meant and how they claimed a “mandate” from the people.

Trump argued that his victory signified the triumph of the people over corrupt politicians. “What truly matters,” Trump declared, “is not which party controls our Government, but whether our Government is controlled by the people. January 20, 2017, will be remembered as the day the people became the rulers of this Nation again.”

Biden argued that his victory signified the triumph of democracy and the will of the people over anti-democratic threats. “Today we celebrate the triumph not of a candidate, but of a cause,” declared Biden, “the cause of democracy. The people—the will of the people has been heard, and the will of the people has been heeded. We’ve learned again that democracy is precious, democracy is fragile. And at this hour, my friends, democracy has prevailed.”

President Trump: GPA Photo Archive / U.S. Marine Corps Lance Cpl. Cristian L. Ricardo / DoD; “President Trump’s inauguration” (Public Domain) by US Department of State; President Biden: “210120-D-WD757-2752” (CC BY 2.0) by Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

Presidential Obligations

Most noteworthy, when we look at Trump and Biden’s Inaugural Addresses, we see stark differences in how they understood the obligations of the presidency. While both acknowledged that their inauguration represented the peaceful transferal of power, only Biden promised to defend democracy and the Constitution. Trump vowed instead to defend the nation’s border. Biden used the word “democracy” eleven times in his speech; Trump didn’t use the word “democracy” at all, not once.

In his 2017 Inaugural Address, Trump constituted himself as president as the protector of the national border—which he believes defines the nation. “A new vision will govern our land,” Trump vowed, “Every decision on trade, on taxes, on immigration, on foreign affairs, will be made to benefit American workers and American families. We must protect our borders from the ravages of other countries making our products, stealing our companies, and destroying our jobs.”

In his 2021 speech, Biden constituted himself as president as the caretaker of American democracy and the Constitution—which he believes defines the nation. “Before God and all of you,” vowed Biden, “I give you my word: I will always level with you. I will defend the Constitution. I will defend our democracy. I will defend America.”

Trump has already told us that it’s not his role to protect democracy.

Each president’s campaign poetry and governing prose are evident in their Inaugural Addresses. In examining them we can conclude that Donald Trump is more likely to be a threat to American democracy and the Constitution than Joe Biden.

Why? Because Trump doesn’t see the president’s role as protecting democracy, he sees his role as protecting the nation’s border. That singular focus means that Trump could be willing to be a dictator because assuming unlimited power would enable him to protect the border, which he believes defines the nation. Trump’s beliefs about the role of the presidency could provide him with a justification for using anti-democratic and/or unconstitutional measures or exceeding the limited powers granted to the president to enact the policies he thinks would secure the border.

Biden, however, sees his primary duty as president as upholding democratic principles and constitutional limits. Therefore, he’s unlikely to threaten the American constitutional order.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3U0AVHW