The European Parliament awarded its prestigious Sakharov Prize in October 2016 to two Iraqi Yazidi women who were held as sex slaves by Islamic State militias. Some months before, the International Criminal Court (ICC) issued its landmark conviction of Jean-Pierre Bemba for his responsibility as commander-in-chief for sexual and gender-based violence committed by his troops in the Central African Republic. Both events are evidence of the increasing awareness at the European Union (EU), and internationally, about the need to amplify women’s experiences of violence and their claims to justice. In Guatemala, for example, a court recently convicted two former military officers for crimes against humanity for having enslaved, raped and sexually abused 11 indigenous Q’eqchi’ women at the Sepur Zarco military base during the armed conflict in Guatemala.

The fact that all three of the above events took place in 2016, and the idea that gender and sexual-based violence during conflict is being taken more seriously, even punished, is representative of longer-run processes that can be tied to the 15th anniversary of the Women, Peace and Security (WPS) agenda. Just some months before, in October 2015, the Global Study on the Implementation of UNSCR 1325 was published by UNWomen.[ref]UNWomen, Preventing Conflict, Transforming Justice, Securing the Peace: A Global Study on the Implementation of the United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 (New York, NY: UNWOMEN, 2015), http://wps.unwomen.org/pdf/en/GLobalStudy_EN_Web.pdf [/ref] The study reveals the challenges and lessons learnt through the implementation of the WPS agenda.[ref]The Women, Peace and Security agenda comprises a set of eight resolutions that were adopted by the United Nations Security Council after intense advocacy work by transnational feminist networks. The Agenda codifies the way in which gender influences all aspects of conflict management, prevention and peacebuilding, including security sector reform, demobilisation and reintegration, and transitional justice policies.[/ref] In its chapter on “Transformative Justice”, the Global Study advocates for a broader scope of transitional justice mechanisms that take into account how women’s experiences of violence are related to their unequal status in society and, therefore, connects reparations to broader development policies directed at producing collective and societal forms of redress. In this sense, one could claim that the Women, Peace and Security agenda has had a real impact in awareness-raising in the international community and the development of gender sensitive security and justice policies.

Nadia Murad and Lamiya Aji Bashar receive 2016 Sakharov Prize

© European Union 2016 – European Parliament

Particularly telling is the fact that on 16 November 2015, the Foreign Affairs Council of the European Union presented its framework in support of transitional justice,[ref]General Secretariat of the Council of the EU, EU’s support to transitional justice – Council Conclusions, 13576/15, 16 November 2015.[/ref] effectively making the EU “the first regional organisation to have a dedicated strategy concerning transitional justice”.[ref]General Secretariat of the Council of the EU, EU Annual Report on Human Rights and Democracy in the World in 2015, 10255/2016 (Brussels: General Secretariat of the Council of the EU, 2016), https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/eu_annual_report_on_human_rights_and_democracy_in_the_world_in_2015.pdf[/ref] The document was issued as a response to the commitment in the EU’s Action Plan on Human Rights and Democracy 2015-2019[ref]The Action Plan was created as a response to the commitment in the Strategic Framework for Human Rights and Democracy launched by the High Representative of the EU for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Catherine Ashton, in June 2012. [/ref] to develop an EU framework on transitional justice. In its conclusions, the European Council highlighted the fact that transitional justice is an integral part of the peacebuilding and post-conflict reconstruction agenda of the EU and that, consequently, an EU transitional justice policy needed to comply with the suite of United Nations WPS resolutions. Furthermore, paragraph 8 of the Council conclusions specifies that the EU should prioritise “gender sensitive transitional justice” and, similarly, that gender mainstreaming is a priority. This pledge follows previous commitments to gender mainstreaming in EU peacekeeping and crisis management and in its Common Security and Defence Policy. However, scholarly work suggests that EU External Action policies and practices do not take gender seriously and rather betray a conservative understanding of what a gender sensitive approach is, making gender mean the same as biological sex.[ref]

Roberta Guerrina and Katharine A.M. Wright, “Gendering Normative Power Europe: Lessons of the Women, Peace and Security agenda”, International Affairs 92 (2) (2016): 293-312; Maria Ariana Deidana and Kenneth McDonagh, “It’s important, but…’ translating the Women, Peace and Security (WPS) Agenda into the planning of EU peacekeeping missions”, Peacebuilding (2017); Louise Olsson et al., Gender, Peace and Security in the European Union’s Field Missions, (Stockholm: Folke Bernadotte Academy, 2014).[/ref]

The aim of this working paper is twofold. First, I offer a short overview of what the EU means by a “gender sensitive” approach to transitional justice. Second, I explore whether this approach has transformative potential. Through my analysis, I argue that the EU policy on transitional justice tends to reproduce a conservative understanding of transitional justice that is equivalent to the existing EU conception of the Women, Peace and Security agenda. Although there are some successes in terms of language, such as, for example, an understanding of gender as a relational approach, the framing of, and roles attributed to, women and men expose serious shortcomings. Rather than tackling and transforming deeply rooted norms and practices in which gender inequalities are ingrained, the EU addresses “gender issues within existing development policy paradigms”[ref]Fiona Beveridge and Sue Nott, “Mainstreaming: a case for optimism and cynicism”, Feminist Legal Studies 10 (3) (2002), 300.[/ref] and promotes a gender sensitive approach as “a way of more effectively achieving existing policy goals”.[ref]Sylvia Walby, “Gender Mainstreaming: Productive tensions in theory and practice”. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State and Society 12 (3) (2005), 323.[/ref] This conservative understanding is evident in both how the EU constructs transitional justice, and also how it frames WPS in EU policy discourse. This has implications for the recognition of transitional justice local ownership and agency, as well as for the future of transformative approaches to justice more broadly.

Drawing on Roberta Guerrina and Katharine Wright’s recent work on the tensions shaping WPS in EU external affairs, I analyse the particular understandings of gender, women, peace, and security that underpin the EU policy on transitional justice. Through the analysis, I find that there are challenges for the EU gender sensitive approach to transitional justice in three categories corresponding to Nancy Fraser’s trivalent model of justice, which encompasses representation, recognition and redistribution. Understanding these challenges and overcoming them is essential, as the EU is likely to remain “the largest donor in the area of democracy, rule of law, justice and security sector reform and good governance, gender quality and support for vulnerable groups worldwide”.[ref]General Secretariat of the Council of the EU, EU’s support to transitional justice – Council Conclusions, 13.[/ref] The working paper is structured as follows: the next section explores the linkages between the Women, Peace and Security agenda and transitional justice. The second section examines how the EU understands these linkages. In section three, I provide a brief overview of the 2015 EU framework on transitional justice before delving into an analysis on how this framework integrates the Women, Peace and Security agenda, paying particular attention to how gender has been conceptualised. In this part, I offer a global synthesis of the findings on formal (format, references) and normative grounds (framing, distribution of roles, participation and ownership), detecting disparities and omissions in gender justice provision. Finally, I offer several recommendations for the implementation of a transformative and gender sensitive EU transitional justice policy.

TRANSITIONAL JUSTICE PROMOTION THROUGH THE WPS AGENDA

Transitional justice mechanisms and practices are directed to redress past wrongs, institutionalise the rule of law and construct new legal and normative frameworks in post-conflict contexts or in societies that have suffered occupation, dictatorship or other suppressive situations, in order to prevent violence and war from happening again. Although the United Nations refers to transitional justice measures as a set of judicial and non-judicial instruments and mechanisms, such as trials, truth commissions, lustration, memorials, reparations,[ref]Guidance Note of the Secretary-General on the United Nations Approach to Transitional Justice, 19 April 2010.[/ref] there is not a predetermined set of standards in law or policy on how and whether transitional justice should be applied. Transitional justice practice therefore varies according to the geographical contexts in which policies and discourses on retributive, restorative and even (re)distributive justice are being implemented.[ref]Retributive justice involves punishment of the perpetrator. It is generally associated with court trials. Restorative justice, by contrast, is victim-centred as it seeks to rebuild communities or relationships. It is regarded as an alternative form of justice outside the formal judicial court system, in the form of, for example, Truth and Reconciliation Commissions or Women’s Courts. (Re)distributive or socioeconomic justice provides financial and other material compensation for individual victims or the community. The aim is not only to “compensate” the victims of past wrongs, but also to promote a sustainable peace by changing the structural conditions that rendered violence possible in the first place. [/ref] Although they have been primarily focused on restoring civil and political rights, there is increasing advocacy regarding the need to also address social, economic and cultural rights, as well as collective rights to socio-economic development.[ref]Naomi Roht-Arriaza and Javier Mariezcurrena, eds., Transitional justice in the twenty-first century: beyond truth versus justice (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).[/ref] However, it has not been until recently that transitional justice has been situated as part of peacebuilding processes.[ref]Wendy Lambourne explains that the term “transitional justice” was first used in the context of societies transitioning from authoritarian to democratic regimes and that it was former UN Secretary-General, Kofi Annan, who for the first time made a link between the goals of transitional justice, reconciliation and peacebuilding in the Report of the Secretary-General on the Rule of Law and Transitional Justice in Conflict and Post-Conflict Societies, UN Doc. S/2004/616, 23 August 2004. See Wendy Lambourne, “Transitional Justice and Peacebuilding after Mass Violence”, The International Journal of Transitional Justice 3 (2009): 28-48. Other works on the linkage between transitional justice and peacebuilding are: Alex Boraine and Sue Valentine, ed., Transitional Justice and Human Security (Cape Town: International Center for Transitional Justice, 2006); Rama Mani, Beyond Retribution: Seeking Justice in the Shadows of War (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2002); Tristan Anne Borer, ed., Telling the Truths: Truth Telling and Peacebuilding in Post-Conflict Societies (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2006).[/ref] This new scholarly work suggests that analysing transitional justice as peacebuilding practices provides a more holistic perspective on the links between dealing with the past and reconstructing for the future, enabling a more sustainable peace. From this perspective, transitional justice projects and outcomes have important implications for gender relations in post-conflict societies.

Paul Kirby and Laura Shepherd identified two approaches that could inform the future of the WPS agenda[ref]Paul Kirby and Laura Shepherd, “The futures past of the Women, Peace and Security agenda”, International Affairs 92 (2) (2016): 373-392.[/ref] and that are clearly related to the two ways of combatting injustice – affirmative and transformative – identified by Nancy Fraser.[ref]Nancy Fraser identifies two contrasting approaches to remedying injustice: the first one is an affirmative approach, by which unjust situations are corrected “without disturbing the underlying framework that generates them”. The second is a transformative approach, by which remedies are set up in order to correct unjust situations “precisely by restructuring the underlying generative framework”. See Nancy Fraser, Justice Interruptus: Critical Reflections on the “Postsocialist” Condition (New York: Routledge, 1997), 23.[/ref] The first, more conservative one, consists of making the links between sexualised violence and participation in order to understand how sexualised and gender-based violence prevents women’s meaningful participation in political and governmental spaces.[ref] Similar arguments are found in Gina Heathcote, “Naming and shaming: human rights accountability in Security Council Resolution 1960 (2010) on women peace and security”, Journal of Human Rights Practice 4 (1) (2012): 82-105; Jacqui True, The political economy of violence against women (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012); Jana Krause, “Revisiting protection from conflict-related sexual violence: actors, victims and power”, in Gender, peace and security: implementing UN Security Council Resolution 1325, ed. Louise Olsson and Theodora-Ismene Gizelis (London: Routledge, 2015): 99-115.[/ref] The second approach proposes “an enmeshing of the parallel pillars of the WPS agenda in the process of peacebuilding and post-conflict reconstruction”.[ref]Kirby and Shepherd, “The futures past of the Women, Peace and Security agenda”, 381.[/ref] Kirby and Shepherd point out that this approach directly links transitional justice measures with the WPS agenda, as it focuses on reparations and development, connecting protection, prevention and participation measures at different levels and through a diversity of actors. Indeed, as they argue, if we take into account the way the provisions and principles of WPS cut across the range of institutions and complex processes of post-conflict reconstructions and peacebuilding,[ref]Christine Chinkin and Hilary Charlesworth, “Building women into peace: the international legal framework”, Third World Quarterly 27 (5) (2006): 937-57.[/ref] this second approach would constitute an enabler for gendering transitional justice on a case by case basis. Such a contextual approach is very much in agreement with the foundation of the WPS agenda as a civil society project that takes seriously individual experiences of women and indigenous women’s organisations.

Following the first approach described by Kirby and Shepherd, a range of security tasks to combat injustice are displayed in the suite of Women, Peace and Security resolutions. For example, UNSCR 1888 focuses on access to justice, the rule of law, legal and judicial reforms, investigations and prosecutions. In turn, UNSCR 2106 talks specifically about transitional justice mechanisms, particularly concentrating in punishing sexual violence. On the other hand, several paragraphs in the resolutions composing the Women Peace and Security agenda seem to engage with the second, more transformative, approach. For instance, a crucial enabler of participation, according to UNSCR 1889, is active engagement by Member States with civil society, “including women’s organizations”, in order to address the “needs and priorities” of women and girls. These needs include support for greater physical security and better socio-economic conditions, through education, income-generating activities, access to basic services, in particular health services, including sexual and reproductive health and reproductive rights and mental health, gender-responsive law enforcement and access to justice, as well as enhancing capacity to engage in public decision-making at all levels.[ref]Laura Shepherd, “Sex, Security and Superhero(in)es: From 1325 to 1820 and Beyond”, International Feminist Journal of Politics 13 (4) (2011): 504-521.[/ref] On the same line, UNSCR 2242 recommends “reparation for victims as appropriate”, while highlighting the need to end impunity and the capacity of the Security Council to enact sanctions against those that committed conflict-related sexual violence. The Global Study on the implementation of UNSCR 1325 also calls on the UN and Member States to “[p]rioritize the design and implementation of gender sensitive reparations programmes with transformative impact”.[ref]UNWomen, Preventing Conflict, Transforming Justice, Securing the Peace, 124.[/ref]

The integration of all components of the WPS agenda in transitional justice mechanisms is developed briefly in the 2010 UN Secretary-General report, in which the global indicators tracking the implementation of UNSCR 1325 include both the “number and percentage of transitional justice mechanisms called for by peace processes that include provisions to address the rights and participation of women and girls in their mandates” and the “number and percentage of women and girls receiving benefits through reparation programmes, and types of benefits received”.[ref]Report of the Secretary-General on women and peace and security, S/PRST/2010/22, 26 October 2010, 48.[/ref] However, critical voices underline the fact that gender targeted policies, with regard to access to health services, education, economic strategies, employment opportunities, legal reforms and, ironically enough, even policies on sexual violence, are often side-lined.[ref]Ruth Rubio-Marín, ed., The Gender of Reparations: Unsettling sexual hierarchies while redressing human rights violations (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009); Rashida Manjoo and Calleigh McRaith, “Gender-based violence and justice in conflict and post-conflict areas”, Cornell Int’l LJ 44 (2011): 11-31; Fionnuala Ni Aoláin, Dina Francesca Haynes and Naomi Cahn, On the frontlines: gender, war, and the post-conflict process (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).[/ref] They claim that if we are to ensure all pillars are given equal emphasis and to avoid reproducing gendered and sexualised identities where the international community is identified as saviours of the “brown woman” from the barbaric “brown man”, implementing measures should reflect the theoretical focus on transformative approaches to transitional justice.[ref]

Gayatvi Spivak describes colonial relations between Europe and its colonies in terms of “white men saving brown women from brown men” in “Can the Subaltern Speak?”, in Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, ed. Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg. (London: Macmillan, 1988), 92. Postcolonial theorists argue that white/brown, protector/aggressor, victim/perpetrator binaries and hierarchies continued after formal decolonization, and this with the permanent victimization of the “third-world woman”. See, for example, Geeta Chowdhry, “Engendering Development? Women in

Development (WID) in International Development Regimes”, Feminism, Postmodernism, Development, ed. Jane L. Parpart and Marianne H. Marchand. (London & New York: Routledge, 1995); Jacqui Alexander and Chandra Mohanty, “Introduction: Genealogies, Legacies, Movements”, Feminist Genealogies, Colonial Legacies, Democratic Futures, eds. M. Jacqui Alexander and Chandra Talpade Mohanty (New York and London: Routledge, 1997); Geeta Chowdhry and Sheila Nair, eds. Power, Postcolonialism and International Relations: Reading Race, Gender and Class (London: Routledge, 2002). Nicola Pratt argues that the discourse portrayed in UNSCR 1325 on Women, Peace and Security reveals a continuation of the same binaries and hierarchies underpinning Western imperialism. See Nicola Pratt, “Reconceptualising Gender, Reinscribing Racial-Sexual boundaries in international security: The case of UN Security Council Resolution 1325 on ‘Women, Peace and Security’”, International Studies Quarterly 57 (4) (2013): 772-783.[/ref]

EU UNDERSTANDING OF TRANSITIONAL JUSTICE IN THE WPS AGENDA

As a global security actor and regional organisation, the EU has been increasingly perceived as a key actor in the field of gender, peace and security, both in its policy commitments and in its peacebuilding practices. The European Council published its first document on the implementation of UNSCR 1325 in 2005 in the context of European Security and Defence Policy,[ref]“Implementation of UNSCR 1325 in the context of ESDP”, European Council Secretariat Doc. 11932/2/05, 22 September 2005. See also: Check list to ensure gender mainstreaming and implementation of UNSCR 1325 in the planning and conduct of ESDP Operations, European Council Secretariat Doc. 12086/06, 27 July 2006.[/ref] effectively making the Women, Peace and Security agenda a matter of external affairs. In 2008, the European Commission and the Council ratified the Comprehensive approach to the EU Implementation of the United Nations Security Council Resolutions 1325 and 1820 on women, peace and security.[ref]Council of the European Union, Comprehensive approach to the EU implementation of the United Nations Security Council Resolutions 1325 and 1820 on women, peace and security, 15671/1/08, 1 December 2008, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/ueDocs/cms_Data/docs/hr/news187.pdf. See also Council of the European Union, Revised indicators. Comprehensive approach to the EU implementation of the United Nations Security Council Resolutions 1325 and 1820 on women, peace and security, 12525/16, 22 September 2016, http://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-12525-2016-INIT/en/pdf [/ref] The document is important as it outlines the fundamental principles of integration of the WPS agenda in projects and programmes of the EU and its Member States in the sector of security and justice in fragile, conflict and post-conflict countries. It suggests interventions in transitional justice mechanisms and acknowledges the need to integrate WPS in peacebuilding and transitional justice processes.

Although at first sight revolutionary, as it, for example, clearly understands gender as “encompassing both women and men”,[ref]Council of the European Union, Comprehensive approach to the EU implementation of United Nations Security Council Resolutions 1325 and 1820 on women, peace and security, 4.[/ref] the understanding that gender is a power structure that privileges masculinities over femininities is simplified. Even though admittedly there are several references in the document to gender differences, such as women’s exclusion from decision-making instances,[ref]Ibid., 7.[/ref] gender is conceptualised as an individual attribute that a person has and that is immutable, not as the fluid and multiple power differentials that produce structural inequalities.[ref]Deiana and McDonagh, “It’s important, but…’”, 5.[/ref] Indeed, a closer reading of the revised indicators published in 2016 shows that this conservative understanding of gender remains the same after some years. For example, very few proposed activities concern participation, as the focus is placed on the question of protection against gender-based violence. This already shows an orthodox and apolitical understanding of WPS that strips the agenda of its transformative potential, since a focus on protection makes it very difficult for policy-makers to see beyond the label of women as victims.[ref]Shepherd, “Sex, Security and Superhero(in)es”.[/ref] At the same time, the indicators also propose activities for the empowerment of women, supported through the creation of capacity-building mechanisms that will transform them into agents of their own destiny.[ref]Council of the European Union, Revised indicators. Comprehensive approach to the EU implementation of United Nations Security Council Resolutions 1325 and 1820 on women, peace and security, 18.[/ref] The Comprehensive approach, therefore, does not seek to uncover the structural dynamics that harm feminised subjects disproportionately over masculine power, but rather equip women to be prepared to fill in spaces in governance and peace building spaces whose gendered dynamics remain unchallenged.

What is more, the language contained in the few paragraphs that describe the proposed activities dedicated to participation in transitional justice and peacebuilding reproduce a problematic understanding of gender that (almost) equates it with women. For example, paragraph 14 is specifically directed to “[s]upport to empower women and to enable their meaningful participation and the integration of gender and WPS issues in peace building and transitional justice processes”.[ref]Council of the European Union, Revised indicators. Comprehensive approach to the EU implementation of United Nations Security Council Resolutions 1325 and 1820 on women, peace and security, 17.[/ref] In the language of the two indicators proposed to achieve this, gender appears only once, while women and women’s organisations appear four and two times respectively. The word “men” does not appear at all. Furthermore, the first indicator quantitatively measures the “number and type of peacebuilding and transitional justice activities in which the EU and its Member States provide specific support to enable women’s meaningful participation.” The second indicator looks at examples of best practices of “capacity building of women and women’s organisations to assist their involvement in and/or monitoring of peace building and transitional justice processes” and of “EU-supported consultations with women and women’s organisations to ensure their involvement in peacebuilding and in the design and implementation of transitional justice mechanisms”. The last part of the indicator goes back to the protection and support approach, as it looks for best practices in “addressing the challenges encountered by female victims in accessing justice or redress for violations” and in “[a]wareness raising and outreach activities to ensure that women are informed of ongoing peacebuilding and transitional justice processes and to facilitate their involvement.”

The purpose of the indicators is clearly to develop strategies that ensure empowerment and participation of women in government and peace-building. Yet, this is done by constructing women as a homogeneous group that has the gender attribute of femininity and therefore, that shares an imaginary woman’s standpoint equated with victimhood and with peacefulness. This silences and naturalises differences and inequalities amongst women. What is more, the indicators that directly link transitional justice with the WPS agenda clearly correspond to the first approach identified by Kirby and Shepherd on the future of WPS, where the important task is to uncover the mechanisms by which sexualised and gender-based violence prevent women from participating in public life. The Comprehensive approach and its implementing document do not merge the three pillars, connecting protection, prevention and participation measures at different levels, as required by a transformative approach to peace-building and justice. In failing to do so, they are ill-equipped to challenge “the underlying structural causes of armed conflict, in particular the inequitable distribution of global power and wealth, which continues to be reflected in poverty-stricken peacekeeping economies”.[ref] Diane Otto, “Women, Peace and Security: A Critical Analysis of the Security Council’s Vision”, LSE Women, Peace and Security Working Paper Series 1 (2016), 26-27. [/ref]

GENDER IN THE EU FRAMEWORK ON TRANSITIONAL JUSTICE

In this section I conduct a discourse and textual analysis of how the EU constructs gender in its framework on transitional justice and related documents that make reference to gender justice and gender mainstreaming. I analyse which issues are considered to be gendered and how this conceptualisation informs which solutions are proposed. This means that I analyse not only to what extent roles are attributed to both men and women and to what extent standards, norms and behaviour of men and of women are questioned, but also to what extent there is a particular normative understanding of what gender sensitive transitional justice is and is not. Here I contrast and compare the EU approach with the trivalent model of gender justice based on recognition, representation and redistribution offered by Nancy Fraser.[ref]Nancy Fraser, Scales of Justice: Remaging Political Space in a Globalizing World (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009).[/ref] The model, which is also employed by Louise Chappell in her analysis of the politics of gender justice at the International Criminal Court,[ref]Louise Chappell, The Politics of Gender Justice at the International Criminal Court: Legacies and Legitimacy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016).[/ref] aims to tackle what Fraser’s identified as the three dimensions of gender (in)justice: economic, socio-cultural and political. In order to combat socio-cultural injustices, Fraser upholds recognition through “revaluing disrespected identities and the cultural products of maligned groups”.[ref]Fraser, Justice Interruptus, 19.[/ref] Second, she advocates for economic redistribution through “redistributing income, re-organizing the division of labour” and third, in order to overcome the political dimension of gender injustice, she highlights the need for better representation of women and their interests in terms of the decision-making rules and procedures designed to claim justice and also in terms of individual and collective access to claim for recognition and redistribution.

I reach the conclusion that the discursive subtext remains similar to the Comprehensive approach to the EU implementation of the United Nations Security Council Resolutions 1325 and 1820 on women, peace and security, showing not only a narrowing down of the future of the WPS agenda, but also a conservative understanding of what constitutes gender sensitive transitional justice. This has implications both for the recognition of transitional justice local ownership and agency, as well as on the future of transformative approaches to justice more broadly. I do this by using NVivo 10.[ref]NVivo is a software used for qualitative data analysis.[/ref] The methodology is based on an understanding of policy documents as containers of two dimensions: a diagnosis (what is the problem?) and a prognosis (what is the solution?).[ref]For a similar methodological exercise on EU Development policy, see Petra Debusscher, “Mainstreaming gender in European Commission development policy: Conservative Europeanness?” Women’s Studies International Forum 34 (2011): 39-49.[/ref] In both dimensions, there is an implicit or explicit understanding of what constitutes the problem, who is responsible for solving it and what policies and solutions are needed and possible.[ref]Emanuela Lombardo and Petra Meier, “Framing gender equality in the European Union political discourse”, Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society 15 (1) (2008): 101-129.[/ref] Other solutions and policies are left out as they are deemed impossible or inefficient.

Overview of the EU Framework on transitional justice

The EU’s Policy Framework on support to transitional justice sets out the way in which the EU can engage in helping ensure transitional justice for correcting situations of past abuses in partner countries. It does so by bringing together in a single document references to various aspects concerning principles, policies and instruments on transitional justice scattered in different EU external policies, from the EU Common Foreign and Security Policy to the EU policy on Human Rights and Democracy promotion. In the document, the EU indicates that the EU Policy Framework has two objectives: “to strengthen the EU’s position on transitional justice” and “to promote a comprehensive approach to transitional justice” in order to achieve “peaceful, just and democratic societies.” In its introduction, the Council proposes a very progressive approach to transitional justice, claiming that any such justice must be “locally and nationally owned, inclusive, gender sensitive and respect states’ obligations under international law”.[ref]General Secretariat of the Council of the EU, EU’s support to transitional justice – Council Conclusions.[/ref] The EU Policy Framework is divided into four distinct parts (see table 1). In the first part of the document, the EU relies to a great extent on the UN Secretary-General’s report “The Rule of Law and Transitional Justice in Conflict and Post-conflict Societies”, in which four mechanisms for providing justice are enumerated. As far as the second part of the document is concerned, the Council highlights at numerous occasions the need for a “flexible” approach, which it understands as a combination of a study of the context and the viability of the mechanisms proposed. The third and the most interesting part of the document proposes actions for implementation of the EU Policy Framework, in particular at the European External Action Service (EEAS) and in EU missions. The last part deals with annual reporting, monitoring and evaluation activities.

Table 1: The EU’s Policy Framework on support to transitional justice: elements, guiding principles and main actions.

Table 1: The EU’s Policy Framework on support to transitional justice: elements, guiding principles and main actions.

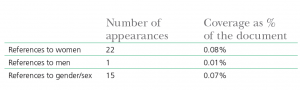

Formal grounds

Two formal aspects of the text The EU’s Policy Framework on support to transitional justice are analysed. First, I conducted a text search on the document to references that relate only to women (looking for terms such as woman, women, girl(s), mother, female), terms related only to men (looking for terms such as man, men, boy(s), father, manhood, male) and references that refer to both (gender, sex, sexual, parenthood). This word count is the first step in assessing the formal presence of a gender sensitive approach and provides an indication of whether there has been a formal shift from the use of “gender” with “women” interchangeably of the Comprehensive approach to the EU implementation of the United Nations Security Council Resolutions 1325 and 1820 on women, peace and security[ref]Guerrina and Wright, “Gendering Normative Power Europe”, 309.[/ref] and towards the understanding of gender as hierarchical power relations. Secondly, I examine whether gender issues are incorporated into all the separate parts of the EU Policy Framework. The text is scanned for references linked to gender. For so doing, I identified terms such as gender, sex(es), woman, women, female, girl(s), maternal, sexual, reproductive, mother, father, men, man, boy(s), masculinity, femininity, patriarchy/al, feminism, domestic violence, rape, sexual violence, and their location inside the document. From this, I assess to what extent a gender sensitive approach has been adopted in the three main parts of the document.

As seen in table 1, content analysis of the EU Policy Framework shows that there is an overrepresentation of references that relate exclusively to women compared to references that relate exclusively to men. This is evidence of the fact that a gender sensitive approach is understood as proposing solutions to include women in transitional justice rather than to offer a genuine gender mainstreaming approach that involves both women and men equally in transitional justice processes. These results confirm those that Guerrina and Wright had obtained in their analysis of the Comprehensive approach, indicating that there has not been a clear improvement. Although the label is “a gender sensitive approach”, the language analysis reveals that gender is used to refer to women, which contributes to “associate gender issues with women’s ‘problems’”.[ref]Marta Martinelli, UNSC Resolution 1325 fifteen year on (Brussels: European Union Institution for Security Studies, 2015) http://www.iss.europa.eu/uploads/media/Brief_29_Gender.pdf [/ref] Meanwhile, men, masculinities and forms of masculine power are never explicitly problematised. They are only mentioned once in a general phrase referring to equality between men and women. This finding is confirmed and analysed further in the normative grounds section that follows.

When conducting a text search to examine whether gender issues are incorporated into all the separate parts of the EU Policy Framework, I detected that 29 out of 43 references to gender or related terms are found in the paragraph dedicated to the principle of gender mainstreaming. The rest of references to gender are to be found in the introduction. Indeed, gender is nowhere to be found in part 3 of the document that contains implementing measures or in part 4 on reporting, monitoring and evaluation. From this gender analysis, we can therefore conclude that there are no linked action items – no specific mechanism or particular financial means – allocated to make sure that the EU gender sensitive transitional justice is more than just a declaration of principles. The actions to be taken are therefore only those contained in the Comprehensive approach previously analysed and in the Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment: Transforming the Lives of Girls and Women through EU External Relations 2016-2020 documents. This second document does not mention transitional justice once.

Normative grounds

The formal aspects analysis conducted in the first part of this section show that there have been limited efforts at including a gender perspective in every aspect of the EU Policy Framework. Rather, gender is addressed in line with “add women and stir” approaches, as there is one single paragraph (containing principle 7) that mentions the need to comply with other policies pertaining to the Women, Peace and Security agenda.

How is the “gender dimension” framed?

In principle 7, the EU recognises the importance of pre-existing gender inequalities in explaining the nature of the crimes committed and their consequences. Additionally, although the principle understands that victims’ experiences of conflict include sexual-based violence, it recognises that victims also go through “socio-economic violations and gender-differentiated impacts of forced disappearances, torture, loss of family members and other violations or abuses”.[ref]The EU’s Policy Framework on support to transitional justice, Joint Staff Working Document, 15 November 2015, 29.[/ref] It appears to be a very progressive understanding of gender that does not conflate gender with women. What is more, as children are provided a complete different section in the document (principle 8 regards a child-sensitive approach to transitional justice), the document seems to have overcome the syndrome of “womenandchildren” that infantilises women, making them immature creatures unable to make their own decisions and, therefore, in need of protection and tutelage.[ref]Cynthia Enloe, “Womenandchildren: Making Feminist Sense of the Persian Gulf Crisis”, The Village Voice 25 (9) (1990).[/ref] However, in this brief paragraph of 24 lines, the phrase “women and girls” or “girls and women” appears five times. In three of them, “women and girls” are identified as victims in need of protection while in two of them the Council advocates for the need to ensure access to justice and women’s empowerment. This seems to be a step back from the framing of women in the Comprehensive approach and its implementation document that framed women as decision-makers more frequently (41 times) than as victims (31 times).[ref]Guerrina and Wright, “Gendering Normative Power Europe”.[/ref]

What is more, participation is restricted to access to justice as victims and as witnesses, which is the aim of principle 6, directed at encouraging “a victim-centred approach”, somehow equating women and victims. At least, this provides the much needed explanation on what was meant by the vague “to enable women’s meaningful participation” in transitional justice proposed by the indicators in the Implementation document on the Comprehensive approach. This effectively demonstrates a lack of understanding of the various and often conflicted roles that women play during conflict and waters down the most transformative pillar of the WPS agenda. The paragraph finishes off by insisting on the need to end sexual and gender-based violence in conflict and post-conflict situations.[ref]See, for instance, Sara Meger, “The fetishization of sexual violence in international security”, International Studies Quarterly 60 (1) (2016): 149-159. [/ref] In so doing, this concluding sentence seems to relegate other human rights and gendered-differentiated socio-economic violations to the bottom of the agenda, reflecting on the inability to overcome the prioritisation of sexual violence as the consequence of armed conflict in order to extend the focus beyond specific events and single human rights violations. Moreover, there is no explanation whatsoever as to how the “pre-existing gender inequalities” provoke sexual violence in conflict or how these are connected to the differentiated impact of conflict in men and women, persisting post-conflict wider structures of inequality and ongoing harms.

Another important principle of the EU Policy Framework is the idea that peacebuilding and transitional justice measures need to be locally owned. In the EU Policy Framework, it seems as if the connection between local ownership and a gender perspective were in practice easy to achieve together, assuming that local civil society and local government are open to generate the structural changes needed in order to ensure gender justice, concerning for example how rape has been dealt with in traditional courts.[ref]Catherine O’Rourke, “The Shifting Signifier of “Community” in Transitional Justice: A feminist analysis”, Transitional Justice Institute Research Paper 09-03 (2008): 269-291.[/ref] Moreover, in the proposed actions, there is no reflection concerning the design of measures directed at ensuring an upholding of both principles without a prioritisation of one over the other. I am thinking, for example, about institutional reform – one of the four mechanisms composing the EU Policy Framework. More particularly, security sector reform (SSR) and disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration (DDR), which for their most part concentrate on refurbishing the police and the military without challenging gender power relations.[ref]See, for example, Claire Duncanson, Forces for Good: Military Masculinities and Peacebuilding in Iraq and Afghanistan (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013); Maria Eriksson Baaz and Mats Utas, eds., “Beyond ‘Gender and Stir’: Reflections on Gender and SSR in the aftermath of African conflicts”, Policy dialogue n. 9, The Nordic Africa Institute (2012), http://nai.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:570724/FULLTEXT01.pdf [/ref]

Perhaps in an effort to comply with principle 9 and situate transitional justice within the security-development nexus paradigm, the paragraph not only mentions the Comprehensive approach, but also the Joint Commission/EEAS Staff Working document Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment: Transforming the Lives of Girls and Women through EU External Relations 2016-2020. However, although this document focuses on the economic and social empowerment of women, there is no reference to transitional justice mechanisms or economic reparations. What is more, although the document seeks transformation of women’s lives in four pivotal areas – ensuring girls’ and women’s physical and psychological integrity; promoting economic and social rights; strengthening girls’ and women’s voice and participation and shifting EU institutional culture to more effectively deliver on commitments – the EU Policy Framework only refers to the first area. That is, it only engages with the area that specifically deals with physical or sexual violence to women and girls, essentially separating socio-economic challenges from bodily harm.

How transformative are the solutions proposed?

The actions proposed in the document are directed at both EU internal dynamics, and the projects supported on the ground. However, they are much more directed at the internal dynamics of the European External Action Service, the European Commission and EU missions, such as reporting and information sharing procedures, and do not clearly propose actions directed at creating the conditions for the flexible, victim-centred, gender sensitive and child sensitive policy the EU Policy Framework advocates for. Two important consequences can be drawn from this. First, although principle 7 recognises the gender-differentiated impact of conflict and acknowledges survivors of conflict-related sexual violence, it does not propose to transform the “underlying cultural-valuational structure”[ref]Fraser, Justice Interruptus, 24.[/ref] by recognising that identities are multiple and non-binary, fluid and ever changing. That is, there is a simple affirmative recognition that can lead to an essentialisation of differences, constructing at the same time the category of women as homogeneous. As Fraser put it, affirmative recognition strengthens differentiation and promotes reification.[ref]Ibid., 14.[/ref]

Second, and related to the first point, although the third part of the document tries to translate the principles underpinning the EU Policy Framework into actions, the Council proposes no action concerning principle 7 on the respect of gender equality and gender justice commitments of a gender sensitive approach. For example, the Council proposes that EU Special Representatives’ mandates include the promotion and support of transitional justice, as they support stabilisation and reconciliation processes and contribute to negotiation and implementation of ceasefire agreements. However, the EU does not have a Special Representative on Women, Peace and Security, and therefore, no representative that will carefully look at how the provisions of the agenda are translated and respected in the implementation of gender sensitive transitional justice mechanisms. That is, top-down representation is still lacking. Bottom-up representation is only partially present, as even when participation of civil society or victims is addressed, it is to a great extent directed at producing input on EU policies. Although the document acknowledges the importance of local civil society’s participation and encourages the “active participation of the victims”, little attention is paid to the work of grassroots activists, or even citizens, who lack a formal institutional platform and who organise in more informal initiatives for the construction of transitional justice. For example, local gender justice practices may have similar goals to but predate the arrival of EU or other international peacebuilding and reconstruction efforts. The EU presents its gender sensitive approach as a model of virtue that assists victims of sexual and gender-based violence in transitioning countries who cannot speak or help themselves. There is no real place for the voices of women or their organisations to shape what kind of transitional justice is needed and which measures should be implemented. In addition, the narrative fails to recognise the plurality of actions already taking place on the ground, delegitimising the achievements of a whole range of feminist activists. This is also evidence of a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach towards gender equality that is not context sensitive, in contradiction with another one of the principles of the EU Policy Framework.

Third, as far as redistribution is concerned, although there is a growing understanding that men and women experience conflict differently and that therefore, they have “differentiated needs with respect to accessing and benefiting from transitional justice mechanisms and processes,”[ref]General Secretariat of the Council of the EU, EU’s support to transitional justice – Council Conclusions, 13.[/ref] there is no specificity as to how the design of reparation programs could redress women in a fairer manner. What is more, the Comprehensive approach does not mention reparations or redistribution, and although we could suggest that Transforming the lives of Women and Girls is the legal framework for action on socio-economic rights, the document seems to adopt a very instrumental approach to gender, in which the inclusion of women is not a matter of justice, but rather serves to achieve other goals in a more effective way. In this respect, it marks a departure from the understanding of a rights-based approach of the EU Policy Framework enshrined in principle 5 and which sees gender equality as an end in itself, towards a neo-liberal consideration of why integrating a gender dimension in external policies matters. Indeed, the Transforming the lives of Women and Girls working document assumes that women, due to their sex differences, will increase operational effectiveness, implying for example that women inclusion is related to less corruption and more economic growth.[ref]European Commission, “New framework for gender equality and women’s empowerment: transforming the lives of girls and women through EU external relations 2016-2020”, Joint Staff Working Document, SWD (2015) 182 final, 21 September 2015, http://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/sites/devco/files/staff-working-document-gender-2016-2020-20150922_en.pdf[/ref] This runs contrary to a transformative transitional justice project. In such a project, EU-sponsored collective measures to achieve significant redistribution of material resources are needed in order to improve the social status of war-affected women.

CONCLUSION

This working paper has done two things: First, it has offered an overview of the EU Policy Framework on support to transitional justice and its understanding of gender justice. Second, the paper has demonstrated that the EU has a conservative normative approach towards gendering transitional justice. It is clear that, although the EU labels its approach as inclusive, flexible and gender sensitive, the actions proposed do not follow suit. In 2017, the EU and its Member States continue to be the world’s largest aid donor and a champion in normative international peace and security. Despite the relative decline of the EU in the global scene, the aspiration of being a global political actor remains, with the clear aim of promoting justice and human rights values and principles, and leading on peacebuilding and transition to peace policies. Pending the first monitoring and evaluation reports on the implementation of the EU Policy Framework, the paper argues that as it stands now, the EU Policy Framework is ineffective in empowering gender sensitive transitional justice solutions in war-torn and post-conflict regions. A discourse analysis of the EU Policy Framework has shown that the EU offers a conservative understanding of gender, following the same narrative used in the Comprehensive approach to the EU implementation of the United Nations Security Council Resolutions 1325 and 1820 on women, peace and security. Although there are some successes in terms of language, such an understanding of gender as a relational approach, the framing of, and roles attributed to, women and men, and the possibilities imagined for equal participation exposed serious shortcomings.

Although aware of the perils of an overarching ambitious transformative goals on the EU transitional justice agenda,[ref]Pilar Domingo, Dealing with legacies of violence: transitional justice and governance transitions, ODI Background note (2012) https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/7686.pdf[/ref] more specific actions pertaining to representation, recognition and redistribution directed at transforming the gender dynamics that contributing to conflict are needed. If that is not the case, when confronted with concrete situations that require paying closer attention to gender dynamics, the European Union will continue to face great difficulties in ensuring coherence and reconciling its objectives and policies on the ground, including its financial mechanisms. If the EU directs its normative potential and high levels of expenditure on retributive and restorative transitional justice that limits the understanding of what is a “gendered sensitive approach” to crimes concerning (only) sexual violence, it also perpetuates the idea that the WPS agenda is directed at protecting women from (sexual) violence and at empowering women as participants and democracy promoters as key to security, development and international stability.[ref]Hillary Clinton, Remarks at the 10th anniversary of UN Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security, 26 October 2010, http://www.operationspaix.net/DATA/DOCUMENT/4123~v~Women_as_Peace_Builders__On_the_Ground_and_at_the_Table.pdf[/ref] In what follows, the paper gives a series of recommendations in order to ensure the EU implements the EU Policy Framework in a truly gender sensitive manner and reorients its focus from tokenistic inclusivity of women and minorities towards social transformation.

+ RECOMMENDATIONS – towards a transformative gender sensitive EU policy on transitional justice

As the EU Policy Framework is still in its infant years, and the first report regarding its implementation has not seen the light of day, this section offers recommendations for the development of actions directed at facilitating a transformative approach that restructures the generative framework of gender inequalities. This approach is based on an understanding there is a need to avoid depoliticisation of gender mainstreaming through toolkits, checklists and other box-ticking mechanisms as well as to acknowledge institutional and even individual complicity inside the EU in reproducing gender power relations. Such an approach helps identify the continuity of violence from wartime to peacetime and to avoid binaries, as it privileges ethnographic sensitivity, contextual specificity and a sophisticated understanding of the similarities but also the differences across individual experiences of gender and power.

On representation – overcoming political injustices

- That the EU informal task force develops a clear set of guidelines that will help translate the WPS commitments more clearly in the EU transitional justice policy. This can be done through the creation of a coordination platform for those involved in the implementation of WPS in the EU. The direction of the platform could be shared between a representative of the EU informal task force on transitional justice and a representative of the EU informal task force on gender and human rights.

- That the EU gives consideration to the creation of a Special Representative on Women, Peace and Security. Although a positive step, the appointment of a Gender Adviser within EEAS does not go far enough. Higher seniority, direct contact with the EU High Representative and visibility are needed in order to strengthen EU’s commitments of gender mainstreaming in peacebuilding and development policy.[ref]For a longer and more developed rationale on this topic, see Guerrina and Wright, “Gendering Normative Power Europe”.[/ref] Indeed, other regional organisations, such as NATO and African Union have appointed a Special Representative and a Special Envoy respectively, and have been considered as examples of best practice for other regional organisations to follow by the Global Study on the implementation of UNSCR 1325.

- That the EU prioritises strategic planning and robust institutional support in the field for gender mainstreaming in order to overcome dominance and subordination schemes in transitional justice processes that can (re)produce gender hierarchies in the transitional society.

- That the EU Policy Framework identifies the elements that prevent women and other minorities from taking part in legal proceedings and tries to take those into account. For example, the distance between the location of women who need to give testimony and the court; the arrangements these women might have to make in order to leave dependents attended, etc.

On recognition – overcoming socio-cultural injustices

- That the EU makes its implicit bottom-up approach much more explicit in practice by reaching out to an alternative set of actors and taking seriously community-based justice, memory-making and reconciliation proposals, in particular women’s and LGBTQI groups, that appear disruptive and transformative. Informal truth-telling initiatives are deployed more and more by grassroots groups in order to challenge and reinterpret dominant understandings of gender justice.[ref]Christine Chinkin, “People’s Tribunals: Legitimate or Rough Justice.” Windsor Yearbook Access to Justice 24 (2) (2006): 201-220; Alison Crosby and M. Briton Lykes, “Mayan Women Survivors Speak: The Gendered Relations of Truth Telling in Postwar Guatemala”, International Journal of Transitional Justice 5 (3) (2011): 456-476; Shelby Quast, “Justice Reform and Gender”, in Gender and Security Sector Reform Toolkit, eds. Megan Bastick and Kristin Valasek (Geneva: DCAF, OSCE/ODIHR, UN-INSTRAW, 2008); Niamh Reilly and Linda Posluszny, Women Testify: A planning Guide for Popular Tribunals (New Brunswick, NJ: Center for Women’s Global Leadership, 2005).[/ref] Only acknowledging and reaching out to these initiatives can ensure that we do not marginalise and exclude specific individuals or groups, in this case, women and sexual minorities from participating in decision-making processes and institutions.

- That the EU makes available mechanisms through which interactions with civil society and in particular women and indigenous organisations can occur in EU Delegations on a regular basis.

- That the EU finds more creative ways of putting forward alternative readings of women’s and men’s roles in society. For example, peacebuilding and development programs could fund projects in the arts, in media and in popular culture, which are more likely to transform societal views on gender than traditional transitional justice mechanisms.

On redistribution – overcoming economic injustices

- That the EU considers the creation of a reparations fund through an Instrument for Justice, similar to the Instrument for Stability.

- That funds be made available to build links with research centres, strategic organisations and universities. The EU could leverage the extensive research expertise in this area, in order to ensure that the implementation of the EU Policy Framework pays due attention to gender as a power dynamic as well as the roles and representation of women in transitional justice mechanisms.

This is paper 5/2017 in the LSE Women, Peace and Security Working Paper Series. Thanks to Laura J. Shepherd and Paul Kirby, for their engagement, careful reading and insightful suggestions.

Open PDF version.

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed in this blog post are those of the author(s) only, and do not reflect LSE’s or those of the LSE Centre for Women, Peace and Security.