How do Leave and Remain votes map on to the results of the General Election? Paul Whiteley, Harold Clarke and Matthew Goodwin (left to right) look at what happened to party support on a constituency level. They find Labour seats that voted heavily to Leave either stuck with Jeremy Corbyn’s party or shifted their support from Ukip to Labour. The Conservatives benefited too as voters abandoned Ukip. Ultimately the Brexit effect helped them much more than it harmed Labour. They also conclude that youth and education are currently on Labour’s side.

How do Leave and Remain votes map on to the results of the General Election? Paul Whiteley, Harold Clarke and Matthew Goodwin (left to right) look at what happened to party support on a constituency level. They find Labour seats that voted heavily to Leave either stuck with Jeremy Corbyn’s party or shifted their support from Ukip to Labour. The Conservatives benefited too as voters abandoned Ukip. Ultimately the Brexit effect helped them much more than it harmed Labour. They also conclude that youth and education are currently on Labour’s side.

The 2017 general election produced the fourth surprise in a row in British politics. In the 2014 European Parliamentary elections, the UK Independence Party (UKIP) had stunned the nation after winning the contest and becoming the first party other than the ‘big two’ to win a national election since 1906. Then, in 2015, David Cameron won a surprise majority after widespread expectations of a hung Parliament. The following year Britain shocked the world after voting to leave the European Union (EU). Finally, this year, Prime Minister Theresa May sought a large majority but ended up with a hung Parliament, in effect taking us back to the start of the Coalition government in 2010.

But to what extent was the 2017 election really a ‘Brexit election’, as some claim? The expectation early on was that Brexit would play a decisive role and favour the incumbent Conservatives who themselves had asked voters to ‘strengthen their hand’ for the Article 50 negotiations with the EU. But, as is often the case, the campaign ended up focusing on domestic issues such as pensions, social care and the National Health Service. Brexit was not totally absent but it was side-lined.

One way of exploring whether Brexit influenced the vote is to examine how voting to Leave the EU in last year’s referendum translated into support for the different parties in the 2017 election at the constituency level. Were the Conservatives helped by Brexit and Labour harmed? What role did the collapse of UKIP play in influencing the outcome? And what role did other factors play, such as the ‘Youthquake’, in boosting the Labour vote?

We can begin to address these questions by examining whether voting at the 2016 referendum predicted the party vote shares in 2017, and also looking at the characteristics of constituencies. Let’s start by exploring the influence of the 2016 referendum.

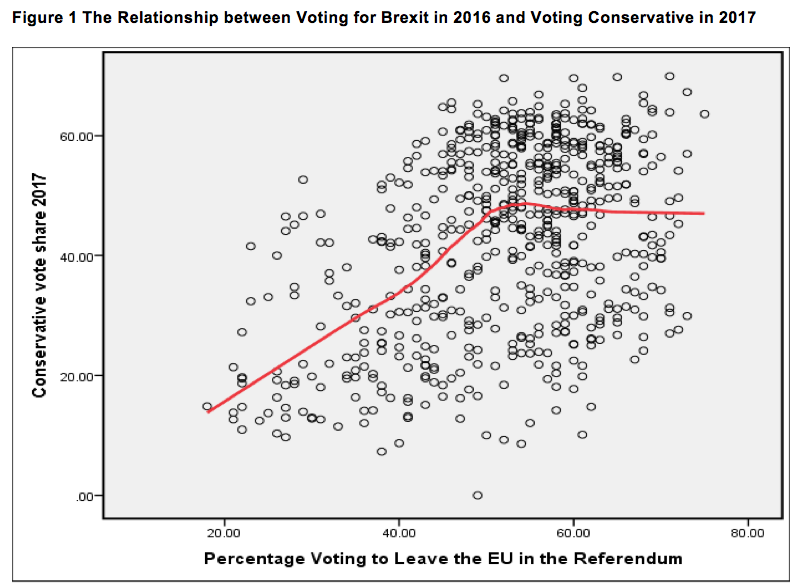

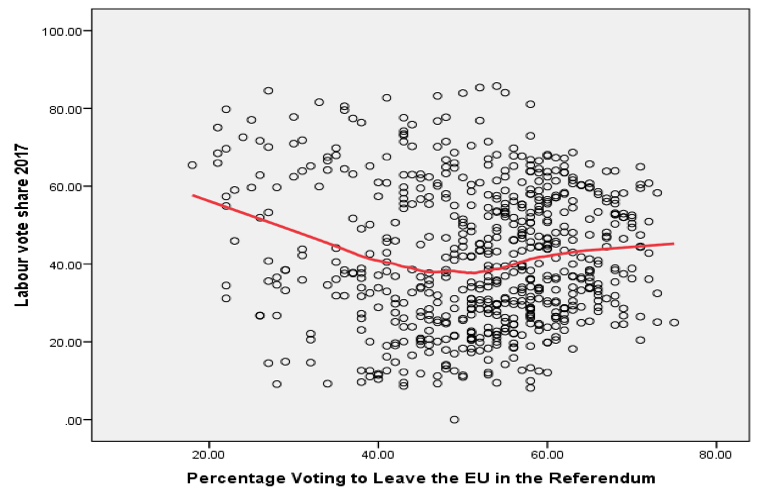

The two charts below show the relationship between the Labour and Conservative vote shares in the 2017 general election and the size of the Brexit vote in the 2016 referendum in all 632 constituencies in Britain. Each dot represents a constituency and the lines summarise the relationship between voting in the two elections. These charts are revealing about the effects of Brexit on the election.

In the range of seats where the vote to leave the EU was below 50 per cent, Labour’s vote in the general election was reduced as support for Brexit increasingly approached the half way mark. But in seats where support for Brexit was well above 50 per cent the Labour vote in 2017 was unaffected. This reveals how voters in safe Labour seats in the North, Midlands and the North East, where Brexit is also popular, did not desert Jeremy Corbyn and his party in the general election. Instead, they stayed loyal.

The pattern of Conservative support is very different. The Conservatives gained support in the constituencies voting to remain as the size of that vote shrank towards a Brexit majority. Once again, as the Brexit votes piled up beyond that, the referendum vote had no influence on Conservative support. That said, the slope of the line summarising the relationship between these measures shows how the Conservative vote was boosted much more by Brexit in the relevant range than the Labour vote was reduced. So, it would be fair to say this was a Brexit election up to a point, but it helped the Conservatives much more than it harmed Labour.

This of course was linked to the collapse in the vote for UKIP, a party that had polled almost 13 per cent of the vote in 2015. If we estimate the relationship between changes in the vote shares between 2015 and 2017 for the four main parties, then a fall in the UKIP vote of 10 per cent increased the Conservative vote by 9 per cent and the Labour vote by just over 5 per cent. Put simply, the Conservatives gained about twice as much as Labour did from the collapse of public support for UKIP. At one stage it seemed likely that almost all former UKIP voters would go to the Conservatives, but this did not happen. Quite a few traditional Labour voters who had supported UKIP in the past and voted Brexit returned to the fold.

Figure 2 The Relationship between Voting for Brexit in 2016 and Voting Labour in 2017

What of the ‘Youthquake’? Data from the 2011 Census allows us to see how a large youth vote in a constituency influenced the election, since it identifies the percentage of people in each constituency aged 18-25 years old. The other side of the coin is to look at the percentage of electors who are over the age of 65.

Estimates show that a 10% increase in the under-25s reduced the Conservative vote by 8% and increased the Labour vote by about 4%. On the other hand, a 10% increase in the over-65s translated almost into a 10% rise in the Conservative vote, pretty much a one to one relationship. However, a 10% increase in retired voters in a constituency had the effect of reducing the Labour vote by 14%. Thus, Labour captured the youth vote but the level of support from this source was eclipsed by support for the Conservatives from the over-65s.

Finally, education gave Labour a strong advantage in 2017. A 10% increase in the population with no educational qualifications gave Labour a boost of 12% in support and reduced the Conservative vote by 16%. These people are by and large unskilled workers who have been longstanding Labour supporters. Given this, one might expect the Conservatives to do well among graduates, but this was not the case. A 10% increase in graduates in a constituency increased the Labour vote by 5% and reduced the Conservative vote by 9%, so many educated voters went for Labour.

These findings have implications for the future. Youth and education are on Labour’s side at the moment. It will be a challenge for the Conservatives to refresh their voter base in the future and avoid being catapulted out of government by a resurgent, left-wing Labour party that has demonstrated surprisingly broad appeal. This presents a big strategic dilemma to the Conservatives –while they appear to have benefitted from a Brexit effect in pro-Leave areas, many of the voters who they need to win over are instinctively pro-Remain or less committed to their Brexit views.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE.

Paul Whiteley, Harold Clarke and Matthew Goodwin are the co-authors of Brexit: Why Britain Voted to Leave the European Union (Cambridge University Press, 2017).

Matthew Goodwin is Professor of Politics and International Relations at the University of Kent.

Paul Whiteley is a Professor in the Department of Government at the University of Essex.

Harold Clarke is Ashbel Smith Professor, School of Economic, Political and Policy Sciences, University of Texas at Dallas, and Adjunct Professor, Department of Government, University of Essex.

Why Britain voted to Leave (and what Boris Johnson had to do with it)

Listen to Matthew Goodwin, Simona Guerra, James Ball & Marta Lorimer discuss why Leave won

1 Comments