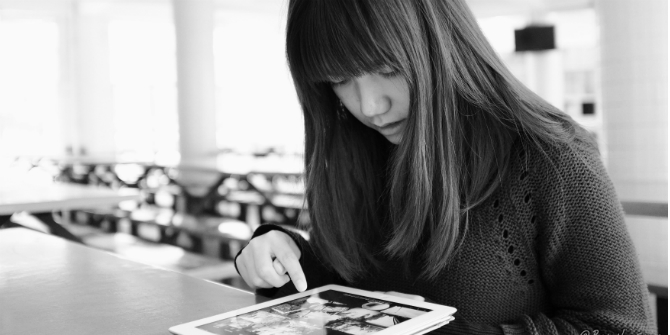

What does it mean to be an adolescent today? Julian Sefton-Green and Sonia Livingstone spent one year with a class of 13- and 14-year-olds – at school, at home, with their friends and online – to find out what they make of everyday life. The book about this research project¹, The Class: living and learning in the digital age, was just launched. Julian is an independent scholar working in education and the cultural and creative industries. He is currently leading the project Preparing for Creative Labour and is a principal research fellow at the Department of Media & Communication, LSE, a research associate at the University of Oslo and visiting professor at The Playful Learning Centre, University of Helsinki. [Header image credit: B. Chan, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0]

What does it mean to be an adolescent today? Julian Sefton-Green and Sonia Livingstone spent one year with a class of 13- and 14-year-olds – at school, at home, with their friends and online – to find out what they make of everyday life. The book about this research project¹, The Class: living and learning in the digital age, was just launched. Julian is an independent scholar working in education and the cultural and creative industries. He is currently leading the project Preparing for Creative Labour and is a principal research fellow at the Department of Media & Communication, LSE, a research associate at the University of Oslo and visiting professor at The Playful Learning Centre, University of Helsinki. [Header image credit: B. Chan, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0]

We think we know what it means to be a child these days…

Most adults reckon they know about children because they themselves were once children. This is a strange kind of qualification. First, we tend to universalise childhood as if the child you once were stands for all children. And second, the childhood you experienced is, for all its similarities to the ones being lived today, structurally, materially and existentially quite different.

At this young age, there is a strange tension between independence and constraints, with very little escaping a controlled routine – young people are frequently monitored, from the time they are made to wake up to the time they are deemed ready for sleep.

- Around a third of those in our study share a bedroom with their sibling(s), and so privacy for them is most focused on the smartphone – helping them be in touch with people of their choice.

- As is common across Great Britain, the school we were working in had a version of school uniform, so what to wear is precisely defined and evaluated.

- At school, children are kept quiet, in order, and moved from classroom to classroom, where teachers dictate the seating.

- Even talk between young people is kept to a minimum – usually being censored and, so even the simplest of social interactions becomes strangely unnatural.

And life at home for these children was beginning to fray. Many were beginning to uncouple from the routines of family life, but hadn’t settled on any other kind of focus. While those who could be engaged in regular structured activities still managed by their parents seemed perfectly happy and enjoyed most freedom, working-class boys in particular seemed at times to be lost.

Paradox of purpose

This paradox of overwhelming structure imposed from the outside and a search for internal purpose often created an existential ennui, leading to what one girl called “the boredom”. When asked about her interest in Minecraft (which at the time seemed to us defining and absorbing) she commented that it was a way to defeat “the boredom”. This, she said, was significantly a sense of isolation – of loneliness, even in the family – as well as a way to occupy time. Yet time was at a premium. Considerable efforts to set homework and to ensure at least the pretence of a meaningful activity seemed all-encompassing, but there may be a disparity between the imposition of tasks and meaning-making from the young person’s point of view.

When we began our research for The Class, a number of colleagues, and even the headteacher at the school where we were proposing to work, suggested it would never succeed. This was partly a question of practicalities: would we be able to elicit the trust of all the members of the class, and would they open up to us? Retrospectively (after we had ‘succeeded’), this scepticism also suggested a deep uncertainty on the part of the school about the possibility of understanding the day-to-day life of young people. It was certainly true that the young people worked quite hard to keep adults out of their lives, and to some extent the extraordinary compliance with daily routine acted as a mechanism to avoid scrutiny and intervention – good behaviour was a way of keeping adults away.

Defeating boredom with digital media

Obvious as it might sound, this was the primary function of digital technology in young people’s lives – a daily, simple way of avoiding scrutiny. There may have been varied investment in the seriousness with which they managed themselves online, and they certainly played with the fashions of new platforms – at the time, Tumblr and Twitter. They got themselves into scrapes with their parents when the first bill for the smartphone arrived, and it wasn’t at all clear what the point of the meaning of much of the chatter with their friends meant. Nevertheless, it was a way of defeating “the boredom”. It was a way of creating meaning and purpose for and by the individual – an existential assertion of agency.

And so, as we sat in the classrooms day after day, as we watched a succession of demands and impositions more obeyed than resisted, as we witnessed the flow of bodies through the school in the hundreds as they dispersed through the streets back to their houses and flats, we felt ever more strongly that the key to understanding childhood or adolescence lay in the meanings we could ascribe to routine. Even the pleasures of repeated contact: When are you leaving home? Where shall we meet? Every day on the way to school these were the clues to the children’s self-struggling to define themselves against all the expectations held for them.

We may all have been children once, but how many of us can put our finger on the repetitions, the boredom of everyday life, as the key to understanding the people we have become?

NOTES

¹ The class: Living and learning in the digital age, published in May 2016, is based on a research project funded as part of the Connected Learning Research Network by the MacArthur Foundation’s Digital Media Learning initiative.

An earlier version of this text was published on DML Central and has been re-posted with permission.