The narrative that automation will lead to mass unemployment and thus people should settle for a basic income rather than good jobs needs to be challenged, writes Ewan McGaughey. He explains how the law can help secure fair wages and working conditions for everyone.

The narrative that automation will lead to mass unemployment and thus people should settle for a basic income rather than good jobs needs to be challenged, writes Ewan McGaughey. He explains how the law can help secure fair wages and working conditions for everyone.

Technology today lets us create a paradise on Earth, where scarcity and poverty will be forgotten, but we’re consumed by dystopian visions. Today, a tiny group of billionaires – Zuckerberg, Musk, Omidyar, and Bezos – are saying automation and robots (which they intend to own) will create mass unemployment. They propose a basic income. By contrast, international law says we all have a fundamental human right to full employment and fair incomes.

Automation will not create mass unemployment, if the law is active

There is academic support for the narrative of mass joblessness from automation. In 2013, it was estimated that 47% of American jobs were ‘at risk’ from automation. This went viral, and Citigroup, Deloitte, McKinsey, and PwC amplified the narrative. Few read the method: ‘with a group of [machine learning] researchers, we subjectively hand-labelled 70 occupations, assigning 1 if automatable, and 0 if not’ by ‘eyeballing’ different tasks. Further, their timeframe was ‘some unspecified number of years’.

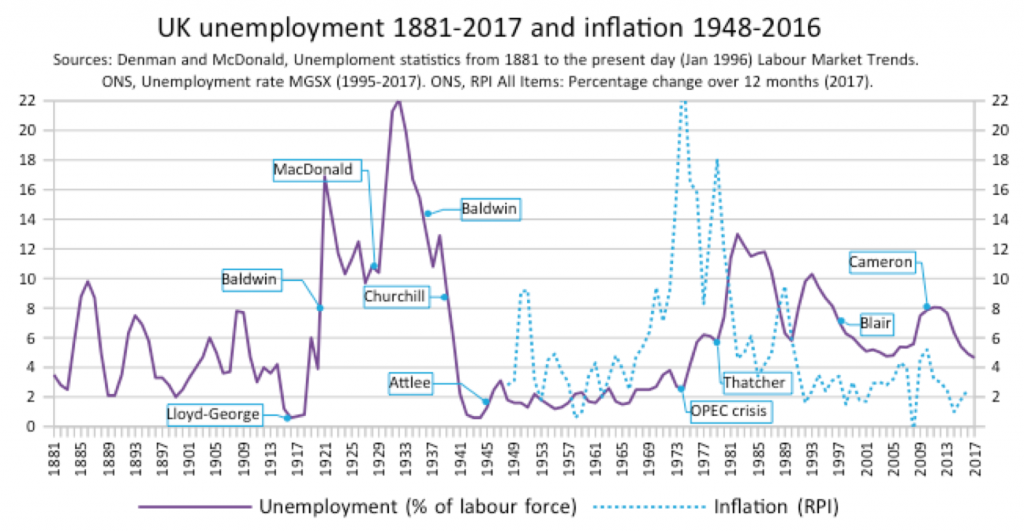

In fact, a leading economic theory was that unemployment is ‘natural’. In 1967, Milton Friedman argued the natural rate was raised by ‘legal minimum wage rates’, pro-labour public procurement and ‘the strength of labor unions’. In 1977 he added unemployment had ‘clearly been rising’ because ‘women, teenagers and part-time workers’ were entering the labour force, and welfare was ‘more generous’. There was never credible evidence for this theory. The best data we have, from Cambridge’s Centre for Business Research, shows labour rights increase employment, decrease unemployment, and spur innovation.

The dominant legal theory, which works, is that we get full employment when the law guarantees full investment: the ‘right to work’ for ‘just and favourable remuneration’ where everyone has ‘social security’. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights is excellent economics.

More paid days off, fair pay

Ironically, John Maynard-Keynes popularised the term ‘technological unemployment’ but knew it was not inevitable. If, like on Animal Farm, machines could work, workers have more leisure. Keynes said we could work just 15 hours a week by 2030. This was plausible. Around the 1920s the word ‘weekend’ was invented, because unions collectively bargained for two rest-days, not just Sunday. Social democracy created ‘childhood’ and ‘retirement’ for everyone. All three are now under stress.

Fair working time and pay requires unions, and democracy in the economy: the right to vote for the boss, and in our pension capital. If we revive voice at work, in a decade we could ‘progressively’ achieve a three-day weekend, triple paid holidays to 84 a year, because it’s been done before. When we unionise, and get votes at work, we get a more equal, prosperous society:

The right to work and job security

To get fair pay and time, we need jobs. That’s why the Universal Declaration guarantees everyone the ‘right to work’ at fair wages, with universal ‘social security’. The idea goes back to Sir Thomas More’s ironically titled Utopia (1516) where he said we must ‘Stop the rich from cornering markets’ and ensure ‘there is plenty of honest, useful work for the great army of unemployed’.

Full employment is possible even despite massive social rupture. After the Second World War, 42% of workers were redundant upon victory from the front and munitions factories. Full employment lasted a quarter century, till evidence-free theories of ‘natural’ unemployment took hold.

Compared to demobilisation, technology is not complex. Take the story of horses and cars. As they rolled out of Ford’s factories, Mr H.B. Brown wrote in the 1908 Yale Law Journal that when cars ‘cease to be a fashionable fad, the public will probably return to carriage and horses’. People would want ‘the companionship of the horse’, not the ‘cold and heartless mechanism of the automobile’. Brown’s prayers were dashed. Mass horse unemployment became a reality, and horse jobs galloped away.

Yet even though one ‘technology’ (the horse) became completely obsolete, left to the market, motorisation took 45 years. This informs the hype around driverless cars: transition may be slow. The proportion of driving jobs is just 4% of the UK workforce. More importantly, people are not like horses. Unlike horses, we vote. We can ensure the right to better jobs on fair pay. Driving can be lonely and stressful. Driving is dangerous: 84,589 dead in avoidable traffic collisions in Europe every year. When we end the bloodshed, the gains can be made green: a ‘no smoking’ policy for motor vehicles.

So, imagine a world where everyone has a good job, with fair wages, and a three-day weekend. Everyone can have a safe, clean, living planet. The only thing that stops us is defective social organisation. But the answers are already there: a consistent set of principles in law and politics since the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

_________

Note: the above draws on the author’s working paper for the Centre for Business Research, University of Cambridge.

About the Author

Ewan McGaughey (@ewanmcg) is a Lecturer in Private Law at King’s College, London and a Research Associate at the Centre for Business Research, University of Cambridge.

Ewan McGaughey (@ewanmcg) is a Lecturer in Private Law at King’s College, London and a Research Associate at the Centre for Business Research, University of Cambridge.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Public Domain.

it happened in the early 1800’s, when you only have to produce for the country with a much lower population in your community you can take more time off, the problem is when you have a capitalist economy where the banks create money and in order to produce you have to pay off “debt” for issued capital as the economy grows so does the “debt ceiling”, instead imagine that the banks can no longer issue money that they don’t physically have and the growth of the economy pays out national dividends to the people based on economic growth performance from a central entity, effectively turning the country into a giant cooperative enterprise, in this example as the efficiency of automation allows productivity to be maintained with less participation the profit of the economy is routed back to the people. such thinking was that of C H Douglas in his book Social Credit written in 1924

I agree with the central thesis that there is no reasonable prospect of technological unemployment, but struggled to understand the rest of the article. It seems to be arguing that we can have full employment if we legislate for it. We can, apparently, also have 84 paid holidays a year because it “has been done before” (where and when?) or that this would magically be achieved if we just had strong unions. In fact, we could have all of these things tomorrow, but only if the population was willing to accept a much lower standard of living.