Green voters are not radically left-wing on economic issues nor are they primarily driven by environmental concerns, finds James Dennison. Instead, the Greens are the natural alternative for disgruntled Liberal Democrats – the party’s prospective voters appear to be of the mainstream, centre-left, but have become dissatisfied with the traditional parties.

Green voters are not radically left-wing on economic issues nor are they primarily driven by environmental concerns, finds James Dennison. Instead, the Greens are the natural alternative for disgruntled Liberal Democrats – the party’s prospective voters appear to be of the mainstream, centre-left, but have become dissatisfied with the traditional parties.

The Green Party of England and Wales has gone from unprecedented popularity to unprecedented scrutiny in 2015. Publications such as The Telegraph, The Spectator, The Financial Times, and even The Guardian have sneered at perceived shortcomings in the Party’s far-left fiscal and immigration policies. Though the Party leadership has long held radical economic views, the above newspapers failed to mention that the Greens also propose a range of consistently popular policies, such as renationalisation of the railways, increasing the minimum wage, removing the profit motive from the NHS, as well as opposition to fracking, HS2 and tuition fees. Besides their role as an environmentalist party, they also have begun to carve themselves a niche as the only party with a clearly non-conciliatory approach to UKIP’s anti-immigration rhetoric and an outright rejection of austerity as an economic policy. The Greens now have the potential to appeal to a number of different sections of the electorate and indeed their polling figures have significantly improved over the last 12 months. What is less clear is the profile of those now planning on voting for Natalie Bennett and Caroline Lucas’s party. Are prospective Green voters of the far-left or are they disgruntled with the mainstream parties? Will they be sincerely voting for the Green’s environmental and economic policies or is their vote a protest? And, if the latter, what are they protesting about?

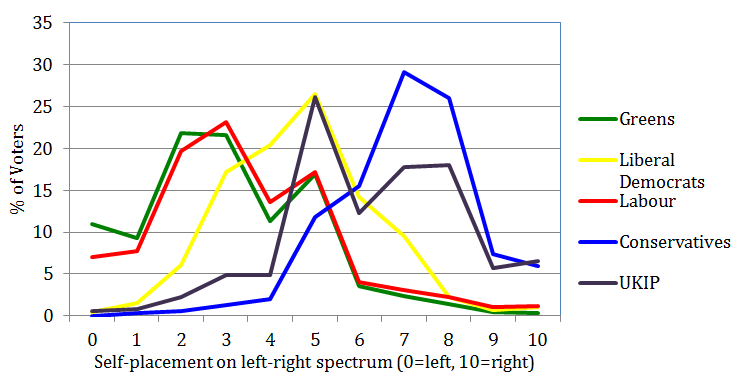

The Green Party’s manifesto is clearly far to the left of Britain’s centre-left Labour Party. While the Greens call for a maximum wage, a universal basic income and increases in social spending, Labour has vowed to cut spending, clamp down on welfare and halt any borrowing in the next Parliament. Yet the clear left-right divide between the parties is not reflected in their supporters, who place themselves almost identically on the left-right spectrum, as shown below in Figure 1. On specific economic policy issues, those planning on voting Green in 2015 tend to be less left wing than Labour voters: 64 per cent of Greens believe the government should redistribute incomes, less than the 70 per cent of Labour voters who believe so. Clearly then, contrary to their party’s policies, Green voters are not of the far left.

Figure 1: Left-right self-placement of each party’s voters

Source: British Election Study Wave 3

Perhaps Green voters’ relative centrism on economic matters is a result of their far greater interest in ecological concerns. After all, the Party’s founding principles and greatest authority are on environmental matters. By looking at what Green voters list as their most important issues, however, we can see that they share relatively similar concerns to those of other voters. Figure 2 shows that the most important issue for those planning on voting Green in 2015 is, like voters in general, the economy. At 12 per cent, the environment is held in far higher regard by Green voters than it is by the electorate in general. Still, this is plainly not a single-issue movement.

Figure 2: Most important issue of Green voters compared to the entire electorate

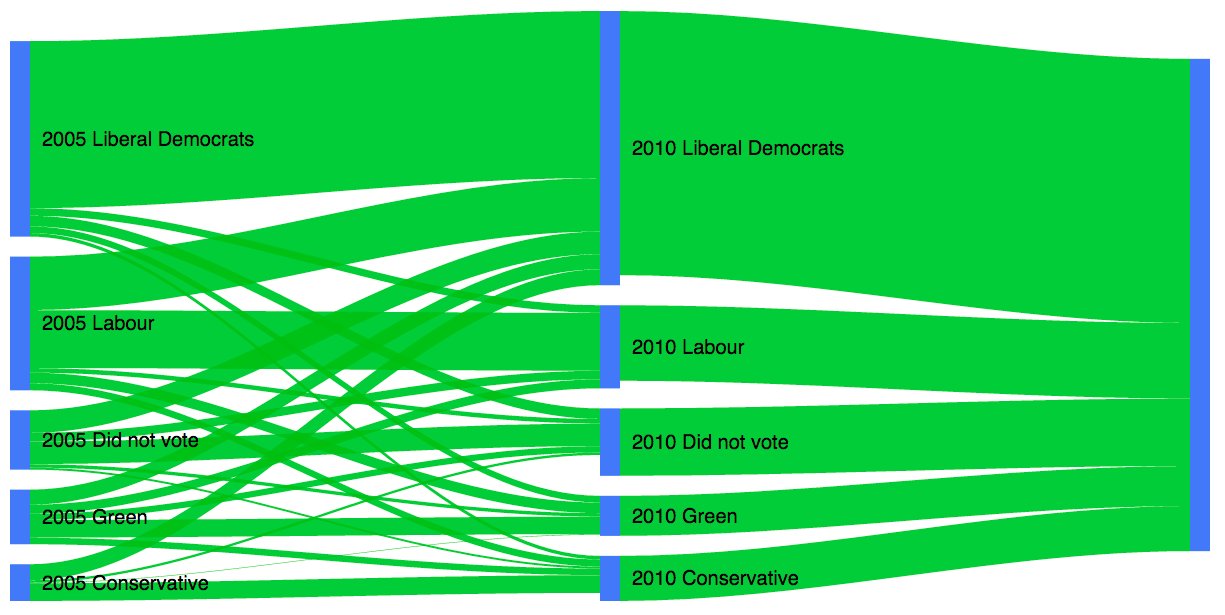

Green voters are not radically left-wing on economic issues nor are they primarily driven by environmental concerns. How, therefore, can we explain their decision to vote for a party with a far-left, environmentalist agenda? One way is to look at who prospective Green voters turned to in previous elections. Figure 3 shows the voting history of 2015 Green voters. Around half voted for the Liberal Democrats in 2010 and around a third voted for the junior coalition partner in both 2005 and 2010. There are a number of ways of interpreting this. First, Liberal Democrats and Green voters traditionally hold similar socio-demographic profiles. Both are likely to be university educated and to work in professional or managerial jobs. Second, the Lib Dems were, until the 2010 election, the protest vote of many on the left. Since entering government, they have lost this niche and, subsequently, have seen their poll ratings plummet. Third, the Greens now have a monopoly on certain policies that they once shared with Nick Clegg’s party – for example, ending university tuition fees. These three issues have made the Greens the natural alternative for disgruntled Liberal Democrats who now have no centre-left party with whom to register their protest.

Figure 3: The voting history of 2015 Green Party voters

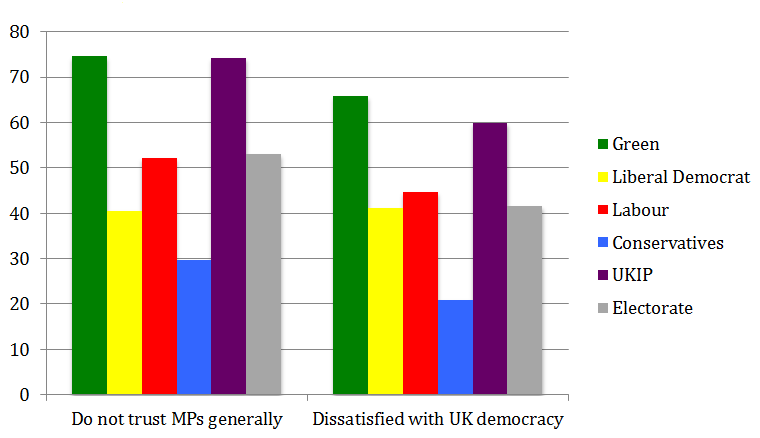

What differentiates prospective Green voters from those who have stayed loyal to parties such as the Liberal Democrats, from which the Greens are taking support? We have already seen that Green voters are to the left on the political spectrum but on policy issues they are no different to Labour voters. It is when we look at attitudes to democracy and the House of Commons that we see a stark difference between the Greens and the three centrist parties. Figure 4 shows the percentage of each party’s voters that do not trust MPs and the percentage that are dissatisfied with UK democracy. Green voters, like UKIP voters, score far higher than voters of other parties on both issues. The recent success of the Green Party may indeed be the result of protest voting against modern British politics as whole, as well as specifically the Liberal Democrats in government.

Figure 4: Attitude to democracy and MPs by party voters

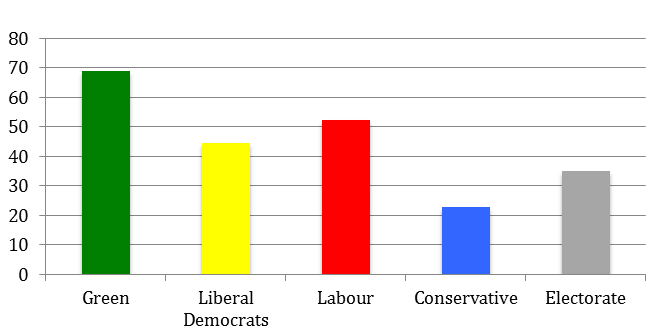

The Green Party leadership have notably avoided the conciliatory stance of the other parties to the rise of the populist, Eurosceptic UKIP and some interviews have suggested that the Greens may benefit from their new niche as the anti-UKIP party. Indeed, as we can see in Figure 5, Green voters are the most likely to strongly dislike Nigel Farage’s party. The increasingly tough immigration rhetoric of the Labour Party may, therefore, have cost them votes to the only vocally pro-immigration party – the Greens. In sum, we can see three protests that Green Party voters are voicing – against the actions of the Liberal Democrats in office, against British politics in general and against the appeasement of Farage’s party by the three centre parties.

Figure 5: Per cent of party voters who strongly dislike UKIP

While the media have profiled the Green Party leadership as ‘completely bonkers’ and ‘pie-in-the-sky’, the party’s prospective voters appear to be of the mainstream, centre-left, but have become dissatisfied with the traditional parties – particularly the Liberal Democrats – over the last Parliament. They are more concerned by environmental issues than most parties’ voters are, but still consider the economy the most important issue currently facing the UK. Though Green voters may be disappointed with the Liberal Democrats in office, it would seem that their grievances with British politics are more systematic, suggesting that their erstwhile motivation for voting Lib Dem was, perhaps already, out of protest. However, their fellow democratic malcontents, UKIP, represent not their ally but, quite possibly a third source of concern around which Green Party voters rally.

Overall, somewhat contrary to the media stereotype of ‘hippie gap year students’ or far-left socialists, Green Party voters look like Lib Dems, think like Labour voters and are as dissatisfied as ‘Kippers. The Green’s current popularity may, therefore, be fragile. If another party is able to both offer a less radically left manifesto while alleviating Green voters’ misgivings about British democracy, the rapidity of the ‘Green surge’ may prove temporary.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

James Dennison is a PhD researcher at the European University Institute. He has previously worked at the Houses of Parliament and completed an MSc in Political Science and Political Economy at the LSE.

James Dennison is a PhD researcher at the European University Institute. He has previously worked at the Houses of Parliament and completed an MSc in Political Science and Political Economy at the LSE.

Please could you provide the source (and link) for the data in figure 2; particular for the “electorate’s most important issue”?

The data you provide is wildly different to a recent bbc/populus poll.

Nicole, sure, it’s the third wave of the 2014-2015 British Election Study.

Jack S, I agree to an extent – LR self placement is about identity but that in itself is a finding and the fact that the two distributions are practically identical is important. I tried to add a policy aspect with the redistribution issue (the defining characteristic of the far left) and found that Green voters were less left than Labour. The conclusion could be applied to any party but is partly derived from the fact that a more established party has the robustness and habitual voters to take knocks.

Re: Labour being to the right of its voters, that may well be true but this article is about the Green Party! Re: Labour not being a centre-left party, well, you might think that but the average Brit places themselves at 5.1 on the spectrum and places Labour at 3.2. All relative I suppose!

Do you have a link for the source of the data for Figure 4?

James, it might be worthwhile subjecting the “self-placement” survey technique to a bit more critique. This sort of survey information produces results that are more about identity than policy preferences and are of limited use in terms of this kind of evaluation. It’s perfectly possible to define one-self as a 5 on the scale and still believe in a lot of the things you’ve described as “Far Left”. The “should the government redistribute income” question is also a potentially fuzzy one in that it’s not linked to any understanding of what exactly that would entail.

Finally, the conclusion seems to have been dragged out of nowhere. Surely, if Labour Party voters think like Green Party voters you could just as easily conclude that the danger was to the former, rather than the latter.

For Populus’s analysis of Green Party supporters based on our polling data, see our Green Index: http://www.populus.co.uk/item/The-Green-Index-Who%E2%80%99s-Voting-Green/

The Green Party gathers momentum because it attracts people who are intelligent enough to understand what is going on out their with man and the planet as well as realising most of need to live at a sustainable level. The Greens are tuned into reality where as Labour comes across as not knowing its backside from its elbow.

Whist finding this article very informative , like other commentators , I’m concerned about the application of the terms, left wing and right wing .

Left and right are fundamentally about stance on “equality”/”inequality”. (originating as such after the French Revolution)

Neo-liberal parties have moved the UK to greater inequality over the last third of a century and that includes New Labour (1997-2010). New Labour was clearly to the right of centre.

Significant distribution of income and wealth would occur under a Green administration making it clearly left of centre.

But the present Labour Party’s policies still don’t seem ones to move things for citizens to greater equality. If this is so Labour is either in the centre or centre right.

The thing is, of course, that it’s not that the Green Party is way to the left of its voters; it’s that the Labour Party is way to the right of its voters.

Anthony Eden, Harold MacMillan, Alec-Douglas Home and Ted Heath were all far to the left of Britain’s “centre-left” Labour Party.

The centre ground has moved so far to the right Clem Atlee may as well have been from another planet.