Throughout the West, patriotism is on the rise, writes Victoria Bateman. During the EU referendum, the issue of sovereignty was high up the agenda. An outpouring of patriotism came along for the ride – a patriotism that Theresa May has since found herself defending on behalf of Brexiteers. But just how much of a threat is patriotism to the economy? Is it truly dangerous, or does it have a hidden economic value? She argues that it can indeed be useful, provided a country is sufficiently outward-looking and the rules of trade are observed.

Throughout the West, patriotism is on the rise, writes Victoria Bateman. During the EU referendum, the issue of sovereignty was high up the agenda. An outpouring of patriotism came along for the ride – a patriotism that Theresa May has since found herself defending on behalf of Brexiteers. But just how much of a threat is patriotism to the economy? Is it truly dangerous, or does it have a hidden economic value? She argues that it can indeed be useful, provided a country is sufficiently outward-looking and the rules of trade are observed.

For many, patriotic sentiment is anathema to global thinking. Being patriotic in a global world is seen as a badge of backwardness: as something distasteful, emotional and unsophisticated. Patriotism and international openness are commonly thought to be at odds with one another – one is either a patriot or a citizen of the world. Yet history shows that there is no need to choose. Patriotism and outward orientation can be successfully combined. Patriotism is not the thing we have to fear. It is our failure to value it and to show how it can be successfully combined with outward orientation that is the problem.

While patriotism brings to mind street parties, a sea of Union Jacks and the Last Night of the Proms, it also has an important economic side. The idea that patriotism can be economically beneficial should be apparent to any member of a successful organisation. Companies thrive where employees have faith in their managers, are united by a clear vision, and can pull together through choppy waters. Educational institutions, such as my own college at the University of Cambridge, have their own identities – identities in which people take pride and which helps motivate their members. Like organisations, countries can also benefit from a healthy dose of patriotism.

To begin with, and to provide foundations for economic growth, it helps to have a state that is able to coordinate and fund vital infrastructure. This requires a wide enough tax base consisting of citizens who are happy to sacrifice hard earned cash, and politicians and civil servants who feel they have a responsibility to the wider country – making for a state which taxpayers can, therefore, trust. As Adam Smith argued in The Theory of Moral Sentiments, we each have an “impartial spectator” sitting on our shoulder, judging our actions from the point of view of others. That explains why in a country that lacks the gel that binds people together, people don’t feel shame when evading taxes or taking bribes. The economy suffers. Where national identity is strong, we tend to be more cooperative, the state is better able to fund vital works and public sector corruption is minimised.

To quote the economic historian Peer Vries:

“The big upheavals that are part and parcel of economic modernisation and international competition can be weathered much better by people who feel they are unified in a nation than by a polity whose population lacks a clear sense of cohesion, identity and purpose”.

While they seem to have been forgotten by modern day growth theorists, both Walt Whitman Rostow’s Stages of Economic Growth and Alexander Gerschenkron’s Economic Backwardness in Historical Perspective emphasised the positive role patriotism plays. And, according to Liah Greenfield’s The Spirit of Capitalism, what unites the economic success stories of Britain, the Netherlands, France, Germany, Japan and the US was the commitment of “masses of people to an endless race for national prestige” which in turn brought an emphasis on “economic competitiveness”.

When patriotism turns nasty is when countries turn inwards. Not only is that politically disastrous, it is economically very painful. Success requires humility. No matter how advanced an economy, and how strong its national identity, there are always ways in which it can improve – which means keeping an eye on the policies and techniques being developed abroad, and welcoming those with ideas and skills that complement the domestic resource base. In the marketplace, companies have little choice but to compete with one another, making it impossible for them to turn their backs on outside developments. While having a strong identity with their own college, academics frequently collaborate and are driven by curiosity about the world outside.

However, countries can lack either the pressure and curiosity needed to resist turning inwards. Humility can be lost in a sea of pomposity.

History shows just how quickly a leading economy can fall behind if it stops being outward looking. For millennia, China led the world technologically and economically. In a drive to catch up, Europeans sought connections eastwards. Unfortunately, the knowledge flow was very much in one direction, allowing Europe not only to catch up but to overtake. Of course, as the richest economy in the world, one can understand why China felt it had little to learn. But it was a major mistake in the longer term.

Lacking competition from neighbouring countries (unlike in Europe), there was little immediate pressure on China to keep an eye on what was going on in the world outside. Ultimately, this left the region vulnerable when distant Europeans made it to Chinese shores carrying silver but also gunboats. The Opium Wars followed and China was literally left addicted.

While some historians have taken to disputing this “inward-looking” story of China’s ultimate decline, the evidence is difficult to ignore. Vries makes one particularly startling point: that China did not come to the defence of thousands of its foreign merchants when they were massacred abroad, including in Manila in 1603, 1639-40 and 1763, and in Batavia in 1740. Britain, by contrast, went to war with Spain in 1739 after they cut off a single captain’s ear. Britain both valued and felt a duty to defend its foreign merchants, including the captain of this particular merchant vessel. China clearly did not.

This idea that China lost its original economic leadership by turning inwards has received renewed interest from Vries. As he points out, China also lacked the kind of patriotism that was common in the newly emerging nation states of Europe, particularly Britain. Unsurprisingly, its tax take was significantly lower than that in Britain (see chart). What China was lacking, Britain certainly had in spades. It was, Vries argues, Britain’s combination of patriotism and outward orientation which allowed it to usurp China and become the leading economy in the world by the nineteenth century, despite having been little more than a backwater to ancient civilisation.

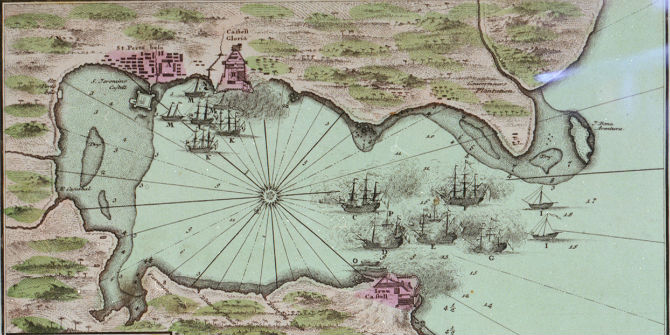

Britain stumbled on the winning formula. As a result, the state was able to raise the funds it needed to finance infrastructure, including the Royal Navy. And, having come from behind, and buoyed by a national spirit, Britain recognised the importance of keeping an eye on economic developments elsewhere, and realised that by trading with the rest of the world and welcoming foreign workers – whether skilled or unskilled – the country could grow in strength. With this economic strength, the state would, they knew, be in a better position to defend itself from foreign incursions and keep its citizens safe.

Per capita tax revenue in grams of silver, 1650-1899

| China | England | |

|---|---|---|

| 1650-99 | 7.0 | 45.1 |

| 1700-49 | 7.2 | 93.5 |

| 1750-99 | 4.2 | 158.4 |

| 1800-49 | 3.4 | 303.8 |

| 1850-99 | 7.0 | 344.1 |

Of course, where “rules of the game” are lacking, the combination of patriotism and outward orientation can lead to international engagements that go too far: moving away from market exchange and towards force. Europe’s colonial past cannot and should not be easily forgotten. However, that doesn’t mean throwing the baby out with the bathwater. Instead, it requires international cooperation, as came in the twentieth century with the United Nations, the International Declaration of Human Rights and bodies such as the European Union, all of which have helped to ensure international dealings were better-mannered.

To defeat the dark side of patriotism, we don’t have to defeat patriotism itself. Instead, we have to make sure that patriotism is combined with outward orientation, along with the international “rules of the game” that ensure these interactions are market-based.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE. A shorter version of this article was originally published in CapX.

Victoria Bateman is a College Lecturer and Fellow in Economics at Gonville and Caius College, University of Cambridge.

Also by Victoria Bateman:

Brexiteers on the left are following a Yellow Brick Road, destined for disappointment

Let’s not conflate Jingoism with Patriotism. True patriotism is taking the hard decisions for ones country and national identity and being comfortable and confident in ones national skin. Jingoism is eschewing all others in simplistic acts of denial and is derived from an overwhelming sense of hubris originating in bravura founded in personal inadequacy. Brexit is jingoism writ large in easy to read print and storybook language.

No Brexit isnt jingoism, its simply a desire to run our own affairs. More worrying is the huge surge in people in the UK who would happily tie our future to a foreign power, the Eurozone, without any understanding of the consequences of being in large nation with one small currency, the pound, and another huge currency, the Euro. The situation is obviously unstable and even if this Referendum had been won by Remain it would only have been a decade or so before the political union of the Eurozone would have created another Referendum where Brexit would have been inevitable.

As it stands, a Lithuanian who cannot read or write or speak English can come to Britain, with no work, and offer his or her services without the employer needing to get a work permit. He or she can compete on equal terms with a British person.

An Australian or Malaysian or Filipino who speaks fluent English and has a PhD cannot. He or she needs to persuade an employer to get a work permit – a barrier for many employers.

if that counts as a fair arrangement as between one group of immigrants and another, it this is what entails an open country, and if this is what is good for the UK, then I am a banana.

I have nothing against Lithuanians, but don’t know why they should have preferential treatment over foreigners from other countries.

“Patriotism having become one of our topicks, Johnson suddenly uttered, in a strong determined tone, an apophthegm, at which many will start: “Patriotism is the last refuge of a scoundrel.” But let it be considered, that he did not mean a real and generous love of our country, but that pretended patriotism which so many, in all ages and countries, have made a cloak of self-interest.”

A real and generous love of our country involves microeconomics and a determination to put country first.

The Remain economic argument is now dead after Q3 growth of 0.5%. All Remain economic forecasts predicted a large reduction in GDP between June and December 2016, its obviously not going to happen. Which leads us to wonder whether the Remain economists were acting under orders…or prejudice.

https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/brexit/2016/10/27/isaiah-berlin-and-brexit-how-the-leave-campaign-misunderstood-freedom/

I think this explains and addresses many concerns more eruditely than I am capable of.

Why do you equate colonial loot with economic progress?