The Leave campaign’s understanding of “freedom” as the absence of external constraints was one-sided, writes Alexis Papazoglou. The UK has autonomously decided to be bound by EU rules and so compliance with those rules has not made it a less autonomous country. Similarly, the freedoms that the UK gains from being an EU member are greater than those it is going to give up come Brexit. More importantly, once out of the EU, external constraints might indeed disappear but so will the UK’s power to freely act in the ways it wants.

The Leave campaign’s understanding of “freedom” as the absence of external constraints was one-sided, writes Alexis Papazoglou. The UK has autonomously decided to be bound by EU rules and so compliance with those rules has not made it a less autonomous country. Similarly, the freedoms that the UK gains from being an EU member are greater than those it is going to give up come Brexit. More importantly, once out of the EU, external constraints might indeed disappear but so will the UK’s power to freely act in the ways it wants.

Freedom has been the core value in the rhetoric of the Leave campaign. Boris Johnson has called for people to “choose freedom” while Nigel Farage has said that 23 June was UK’s “independence day”. But the way that the Leave campaign understood freedom was one-sided and even mistaken. In fact, the Remain campaign’s ideal was also freedom, and ultimately its claim should have been that by remaining a member of the EU, the UK would be more free than if it didn’t.

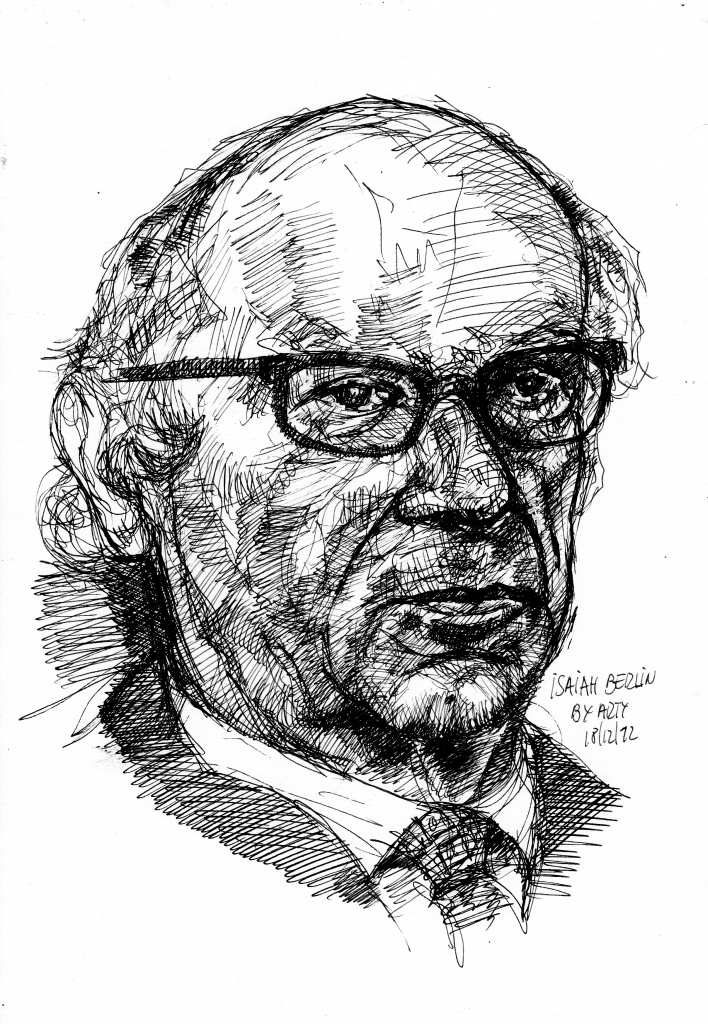

In his classic essay Two Concepts of Liberty, Isaiah Berlin made a distinction between positive and negative freedom. Negative freedom represents freedom from constraints and interferences, and positive freedom represents freedom to do things on one’s own volition. Philosophers have pointed out that Berlin’s analysis in fact contains more than just two concepts of freedom, and that the dichotomy might not be as clear-cut. But at least one way of understanding negative freedom is as freedom from external interference, and positive freedom as autonomy, the freedom to legislate for oneself, to decide the laws that one is bound by.

In his classic essay Two Concepts of Liberty, Isaiah Berlin made a distinction between positive and negative freedom. Negative freedom represents freedom from constraints and interferences, and positive freedom represents freedom to do things on one’s own volition. Philosophers have pointed out that Berlin’s analysis in fact contains more than just two concepts of freedom, and that the dichotomy might not be as clear-cut. But at least one way of understanding negative freedom is as freedom from external interference, and positive freedom as autonomy, the freedom to legislate for oneself, to decide the laws that one is bound by.

Positive freedom

One of the Leave campaign’s main arguments was that by being a member of the EU, the UK has not been free to be the maker of its own laws. In Berlin’s distinction, being a member of the EU undermines Britain’s autonomy. This is to some extent true: some of the laws that the UK is bound by are not voted in Westminster. Yet that does not mean that the UK is not an autonomous, free country. The UK has freely decided to bind itself to the laws of the EU. This is a voluntary participation, and one that can be terminated at any point by a UK government. At the same time, had the UK voted to stay, this would have not have signaled a loss of autonomy, but an autonomous choice to continue to bind itself to EU rules.

The Leave campaign’s claim that the UK’s autonomy is compromised because it is bound by EU legislation was also mistaken because of the way that legislation is made. EU legislation is not conjured up by some arbitrary despot, or ‘faceless bureaucrats’ as it is often said. These laws are democratically decided upon in the European parliament, with the participation of the UK’s representatives, who are directly elected by the citizens of this country. The UK is active in the decision-making process that shapes EU legislation, and as in any democratically-governed institution, it is wrong to claim that participants are not free because they are bound by democratically-arrived decisions.

Negative freedom

So much for positive freedom, but what about negative freedom – that from external interference? Leavers claimed that the EU doesn’t allow the UK to always do what it wants, and that amounts to limiting the UK’s freedom. That’s certainly true. So if the UK government wants to turn away EU citizens who arrive at its borders, for example, it currently cannot. But the limiting of one’s negative freedom in a political context usually also means a gain in negative freedom: the UK might have given away its freedom to close down its borders to other EU citizens, but at the same time UK citizens gain the freedom to cross the borders of all other EU countries without any interference, freely. So one way that the Remain campaign could have responded to that argument was this: the freedom that the UK gains by being a member of the EU is greater than the freedom it gives up. Having access to the common market, having the freedom of movement, of trade, freedom of selling services and so on is far greater a gain in freedom than the freedom the UK gives up.

Most of those on the Leave side of the campaign recognised the enormous benefits that come with the freedoms that the common market provides. The argument was that somehow the UK would be able to negotiate its way into enjoying these freedoms, without giving up any of its own. That would be the equivalent of wanting to live in a society where I am the only citizen enjoying all the negative freedoms everyone else does, but without giving up any of my own corresponding freedoms.

Effective freedom

At the start of this piece I defined Berlin’s concept of positive freedom as autonomy. There is at least one more way of understanding positive freedom, and that is as effective freedom. Effective freedom amounts to having the power and ability to act in the way one wants, and not merely as the absence of an external constraint. Even if one grants to the Leave campaign that the UK’s freedom would be increased in the negative sense if it left – in that it will be free of the external constraint that is the EU – its effective freedom might in fact diminish.

The argument that the Remain campaign often made was that the UK will be less powerful to do the things it wants, including strike international trade deals and influence global issues such as climate change. So even though the UK would be nominally free to do so, effectively it wouldn’t, as it wouldn’t have the power to strike such deals or the capacity to influence the rest of the world. By being a member of the EU, then, the UK’s effective freedom is greater than if it were not, as being a member of the EU makes the UK more powerful and able to ultimately achieve its goals.

The Leave campaign had had a monopoly over the value of freedom at the rhetorical level. But when it comes to actual arguments, the campaign’s understanding of freedom is one-sided and misleading. The Remain campaign had focused on the economic benefits that come with EU membership, shying away from engaging with arguments to do with freedom. Freedom, however, is an emotive ideal, which has proven to be capable of motivating voters, especially those who feel less powerful in society and who yearn for some control over their lives.

This article was originally published on the BPP. Read the original article. This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE. Image credit: Arturo Espinosa CC BY

Alexis Papazoglou is lecturer in philosophy at the Department of Politics and International Relations at Royal Holloway, University of London. For a list of publications see here.

You don’t seem to have “got it” at all. The freedom that you are describing is the freedom that selfish, careeristic individuals such as you and I enjoy and desire.

What Leave wanted was not “freedom”, it was attention. The bulk of philosophers and macroeconomists tend to talk about the world in broad terms, expecting it to be a kaleidoscope that might be configured to have an optimum pattern. The small zones in the pattern that are non-optimal are only transient so do not matter. A group of people in a Nation are a “zone” that would prefer to be protected from the macroeconomic kaleidoscope.

Is that possible? Obviously, even the fact of enhanced separation provides a measure of protection for cultural and behavioural practices that are valued by a population. This separation to be different was the reason for establishing many nations in the first place.

It is almost a macroeconomic orthodoxy to declare that Nations are better off within megastates but when the IMF, OECD etc. came to analyse Brexit they were forced to focus on a hypothetical, devastating “uncertainty” between the Referendum and Brexit as the only real economic reason for supporting Remain. As Q3 economic growth came in at 0.5% this hypothetical uncertainty is now known to be tosh. Inspect WTO vs EEA vs EU long term outcomes and, like the IMF, we find it hard to prove which has the economic advantage for the UK. Of course, it is easy to work out which has the economic advantage for the EU, or for you.

I believe that the key to this whole debate lies in an easy axiom: diversity is simply a good idea.

Good argument! It is a pity stuff like this is only coming out AFTER the referendum result.It was simply assumed during the campaign that most Conservatives, supporting freedom, would support the Leave argument. Yet many arguments supporting freedom could be made by those supporting Remain as well. By giving up some power to the supra-national EU, the United Kingdom’s freedom to act is actually INCREASED overall.

After all the SIngle Market was invented by a British Conservative Commissioner, Lord Cockfield, in the 1980’s and enthusiastically supported at the time by the Conservative PM – one Margaret Hilda Thatcher.

Nations are essential for the exercise of real, public, cultural freedoms. A culture that believes that women must not wear revealing clothing in public, or believes that the land should be at peace on a Sunday or that excessive wealth is an insult to workers etc. cannot coexist in a public space with its antithesis. As homogenising economists, committed to the maximization of output we would label these cultures as “extremist” but we should not have so little self insight that we cannot see that, to another, truly different culture, we are the extremists.

Even where cultures are not so different that they cannot coexist what we achieve by combining them all in a megastate is a new culture that is not any of the original cultures.

Diversity is simply a good thing. Dont destroy it just because the culture where we were born is at its peak of power and can destroy anything that stands in its way.

The natural reason for a nation to exist had never been the need to manage diversity, but to overcome transaction costs in governance. This is why nations in “old Europe” seem to coincide with cultural preferences, religion and language.

Only if transaction costs of governance fall, it becomes natural for supra-national structures to emerge. The USA provides an example of a society that has managed a coexistence of cultural preferences, ethnical roots, religion etc. This was possible because emigrants to the US could self-select themselves into that nation, which was an implicit strategy to achieve low TA cost of governance.

The problem in Europe is that transaction costs in governance have fallen at much slower rate than transaction cost in infrastructure, trade etc. Therefore, economic integration in Europe tends to run ahead of political integration. The outcome is a flourishing economic EU and a stumbling political one. The welfare maximizing solution would be to work on lowering the TA costs of governance. Managing diversity towards symbiotic coexistence might be one way of achieving that.