Brexit may be coming, but the terms are far from clear. In the range between the Norwegian model (membership in the customs union and single market without political participation) and a hard Brexit severing all ties with the EU, and even the long run dissolution of the United Kingdom, anything is possible. History rarely repeats itself, but some structures have a long life, writes Stefan Collignon (LSE). He argues that one of the fascinating features of the Brexit vote in 2016 was that it reflected the old trenches of the English Civil War in the 17th century.

The political map of the Brexit vote resembles the regional distribution of support for the King, Court and Tories against Parliament, Merchants and liberal Whigs. The geography of narrow conservatism and open-minded liberalism does not seem to have changed for centuries. The English Civil War reflected the tensions of early modern globalisation. During the first half of the 17th century, new technologies had created new opportunities for business, but the cost of managing the state had also increased rapidly. The traditional nobility saw a decline in its influence and a rise in the wealth of the gentry and merchants – the result of a tremendous expansion of markets.

It was from this middle class of gentry and merchants that the opposition in Parliament drew most of its support against the crown. They wished to do away with financial and commercial restrictions and resented the King’s interferences with free markets; they also wanted to have a say in such matters as religious and foreign policies, while the King sought to keep control over his traditional economic prerogatives.

Image by Tim Sheerman-Chase, (Flickr), licenced under (CC BY 2.0).

Image by Tim Sheerman-Chase, (Flickr), licenced under (CC BY 2.0).

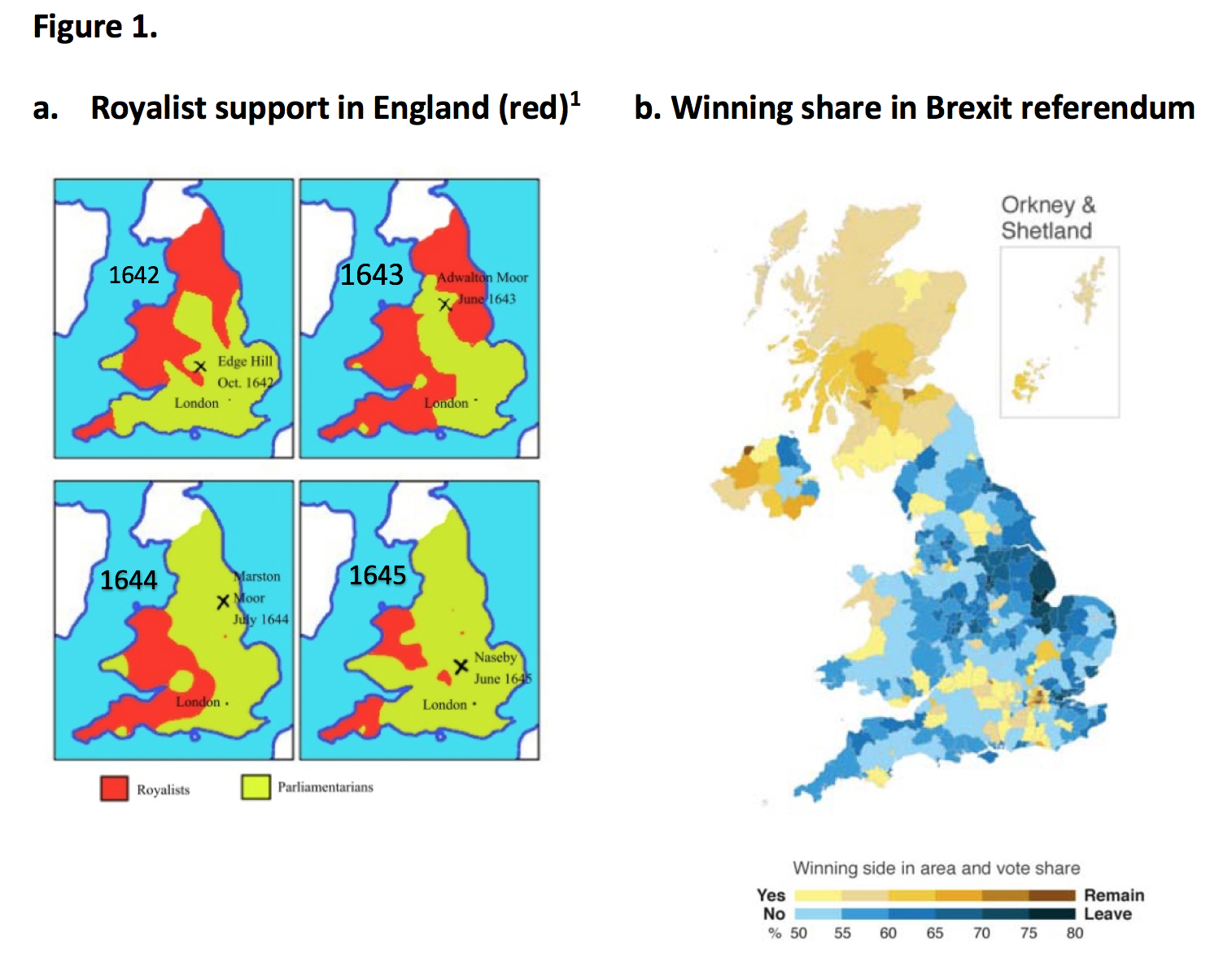

When the Civil War broke out in 1642, London’s economy was diverse and dynamic, closely connected through commercial networks with the rest of England as well as Europe, Asia and North America. But the traditional rural North and the West of England had become impoverished, and this is where the King and his Cavaliers drew support from Catholics and most of the Nobles. Even if the vagaries of the Civil War shifted over time, it is generally true that the strongholds of royalty included the countryside, the shires, and the less economically developed areas of northern and western England. However, the King had no support in Scotland and was paralysed by civil war in Ireland.

The Parliamentarians, by contrast, drew on the richer areas of the South and East, militant members of Parliament, and puritan merchants. The cathedral cities, which profited from foreign pilgrims, and all the industrial centres, the ports, and the economically advanced regions of southern and eastern England were typically parliamentary strongholds. See Figure 1a.

The Brexit vote, too, took place after half a century of accelerated globalisation. Expanding markets have transformed Britain and Europe. New elites have benefitted from fewer restrictions in Europe’s single market, while conservative Tories wish to keep the prerogatives of the nation-state. Europeanisation and globalisation have created winners in the new economy of England’s South and losers in the old industries of the North. The overlap between the maps of England during the “first civil war” in 1643 showing royal strongholds and those of the support for Brexit in 2016 is remarkable. Figure 1b indicates that the leave vote was strongly defended in the North and East and less in the South and West, while Scotland and large parts of Northern Ireland voted remain.

Source: CC BY-SA 3.0

Thus, Britain has effectively returned to the politics of the time before it was a united kingdom. The Brexit vote has opted for the closed society that hopes to preserve the old but will keep the country poor, against the “open society” of improved prosperity for which the European Union stands. It is true that some Brexiters dream about turning the UK into a deregulated “European Hongkong”, but that does not stop them from promoting xenophobic nationalism. By contrast, European integration is based on the liberal idea that opening markets will overcome nationalism and generate a common culture.

What had made Britain the beacon of freedom and democracy after the Civil War was the victory of the liberal Whigs over the conservative Tories. This would have been impossible without the crucial role of Scotland and Ireland in the drama. The Scottish Rebellion forced the King to accept limitations to his sovereignty. Ireland was, at first, a fallback position for loyalists, but coming from outside Cromwell turned Ireland against reactionary Toryism.

Shall we see a similarly decisive role for Scotland and Ireland in the Brexit negotiations? The Scottish Government is now forging ahead with its own EU Withdrawal Bill – despite being told it is beyond the Scottish Parliament’s powers. Scottish nationalists wish to stay in the customs union and the single market and aim for a Norwegian option. A constitutional conflict seems inevitable. And the danger of locking people up behind borders is nowhere more obvious than in Ireland. The UK government has repeatedly stated that it does not want trade barriers between Northern Ireland and Britain, but a hard Brexit is simply not compatible with that option.

While history may not repeat itself, geography imposes constraints on what political actors can do. Scotland and Ireland have saved England from itself in the 17th century. It may well turn out, once again, that Scotland and Ireland will keep Britain open and defeat little England.

This post gives the views of the author, not the position of LSE Brexit or the London School of Economics.

Stefan Collignon is Professor of Political Economy at Sant’Anna School of Advanced Studies in Pisa and Senior Research Fellow at the European Institute of LSE. His most recent book is The Governance of European Public Goods. Towards a Republican Paradigm of European Integration, Palgrave 2018.

A very interesting historical perspective on Brexit and while, on the face of it, it seems to work as an analysis, my own personal experiences are somewhat different. My wife and her family all believe in the roundhead cause in the civil war, but they are all strong believers in Brexit. I realise that this is anecdotal, and may be the exception that proves the rule.

Of course, the world is a different place than it was in 1642, and, hopefully, our Brexit “civil war” will not be fought on battlefields, but it does seem to point to a population evenly split on a completely opposite view of the UK’s place in the world and our path in the future. It seems irreconcilable at present, as did Parliament and the King in the 17th century. Let’s hope the outcome is less bloody.

This map is a much closer match

http://www.viking.no/e/england/danelaw/ekart-danelaw.htm

Royal prerogative has a modern equivalent – treaty prerogative. Inside the EU power is exercised by an overarching authority whose claims to authority override Parliamentary supremacy and which explicitly excludes democratic accountability. Support for such a retrograde and reactionary power structure cannot be described as having either a “liberal” or an “open minded” basis. It is therefore a grotesque distortion to claim that remainers are the heirs of the Parliamentary cause. When remainers can point to an EU equivalent of the Putney debates taking place within the EU structures then they can try to appropriate the mantle of the Parliamentary cause – until then they are exponents of power without accountability – just like the Royalists.

Smearing leavers as xenephobes is low rent argumentation…..

of course its a low rent arguement. the LSE is partially funded by the E.U. – thus those with a pro EU stance have a plateform under guise.

“The Brexit vote has opted for the closed society that hopes to preserve the old but will keep the country poor, against the “open society” of improved prosperity for which the European Union stands. It is true that some Brexiters dream about turning the UK into a deregulated “European Hongkong”, but that does not stop them from promoting xenophobic nationalism. By contrast, European integration is based on the liberal idea that opening markets will overcome nationalism and generate a common culture”

– laughable!- really! really- the majority of brexiters have seen the UK run into the ground through the EU policys and its nefaste influence ( which i will add are the direct principles of the 1950’s and walter hallstein vision- of creating a united states of europe , with centralized powers- concocted after ww2 in the 1950’s doctrine of cold war – what could possible go wrong trying to implement a 1950’s vision of the future, and politics in 2018-(flying cars anyone?)

– looses all credibility at this point and thus should write in the comments section of the guardianista.

– i have remarked the use of the word ‘xenophobia’ prior to brexit was a word hardly used in the press and media, but since brexit it has been used in almost every post with a brexit view written by remainers.

– its like they found a new catchword.

Exactement! Hear, hear!

That is largely because the xenophobia in, mostly English, society, had been hidden until the divisions exposed by the referendum brought it to the surface, back to more general notice.

The word was well known, but its application here was not. Sad, really – and the map correlations suggest that some views have remained entrenched for many generations. ‘Outsiders’ generally not particularly welcome.

The EU has not run Britain into the ground. Before Britain joined the then EEC it was poor, drab, miserable. We had to keep candles because of the frequent power cuts, rubbish was piled up on the streets, three day working weeks and strikes were the norm. Going to the Wimpy bar as a kid was an exotic treat.

What many Brexiters equate through dreamy eyes of life before the EEC is not how monochrome and dreary the country was but that there were fewer immigrants.

It may have been drab where you lived, myself grew up in the 70’s uk, and it wasnt as bad as you portray. Nowadays its returned to victorian styled slums- beds in sheds-people traffickers, rampant prostitution, and murders. It was never as bad as it is today in the 70’s and 80’s. Europes open door policy didn’t just welcome the educated and workers. As was stated to me by some of my polish friends “if you got big police record and can go nowhere, go to uk-they don’t check”. Europes policys have run down wages, increased job precarity, increased violent crime. A seedy, crime ridden area it has now become. Glad we are very soon out and can introduce a decent migration policy. And deport.

Historians prefer the term ‘The War of the Three Kingdoms’ today rather than “English Civil War’ to emphasise that there was more to it than England.

The English parliament beheaded Charles I; he was also King of Scotland, then an independent country, and of Ireland, then a quasi-independent English fiefdom.

Brexit is likewise about English nationalism; the Scots and the Northern Irish rejected it.

Now, the EU negotiators are saying to the English ones, ‘get on with sorting Ireland, and once that is done we can discuss things further’.

Wales also voted for Brexit, as indeed did 1 million Scots and 400,000 Northern Irish.

“The Brexit vote has opted for the closed society that hopes to preserve the old but will keep the country poor, against the “open society” of improved prosperity for which the European Union stands.”

Now there’s a loaded and unfounded statement if ever I saw one. I could retort with the EU is dragging 8.5 billion net out of our economy, and mass immigration from poorer countries dragging down our wages, sending their money abroad and thus ‘keeping the country poor.’

But all this pales into insignificance compared to the effects of mass immigration by non-EU citizens on our way of life in our crowded island. Many of us know what the EU’s plan is (as directed by the UN) – turning Europe into Eurabia. But of course it never gets a mention from you LSE people. Is that because you are unaware of this very obvious fact? Or are you party to the plan? I see nothing but trouble ahead and if civil war does occur then the entire blame falls on the EU, our utterly pathetic governments over the last few decades, the lefties & liberals, apologists and handwringers and all those suffering from some sort of guilt complex who actually believe that the current invasion by young Muslim males are “refugees.”.

“Now there’s a loaded and unfounded statement if ever I saw one” is a bit rich coming from someone who goes on to say “Many of us know what the EU’s plan is (as directed by the UN) – turning Europe into Eurabia.” As to “obvious facts”, it sounds like you need to get out a bit.

Clearly you have absolutely no idea what is going on. I should feel sorry for you, but on the contrary I feel utter disdain for those with their heads buried in the minutiae of the EU, without being able to see the overall plan. You will eventually wake up when it’s far too late to find Europe destroyed. You need to do a lot more research.

As for ‘you need to get out a bit’ – “Always accuse the other side of which you are guilty.” (Josef Goebbels).

Although a Remain campaigner, I seized on this, in the hope of it providing something to smooth the hard edges off Brexit division on my area (Romney Marsh, Kent), where many people take an interest in history.

Unfortunately the Brexiters will pick up on the Remain biased paragraphs and conclusion and the maps, well, don’t map. I should also say that some of the Brexit voters’ comments here invite contempt, the very thing I had hoped to dispel.

I took this article as tongue in cheekish but my 2 pence is that we could also look at it from a political view as opposed to an economic one.

One of the drivers of the Civil War was that the Pope at the time was granting more powers to the Kings across Continental Europe and the Catholic King here wanted those powers here. Parliament did not want to Grant them. This is akin to more political powers being exercised over the UK people today with the agreement of the establishment (akin to the Royal Court of old).

Of course the stalwart people of the British Isles saw off these blatant interfering in their lives and took back control and the rest is history. A period of very successful innovation and wealth creation.

As they say history repeats.

I should proof read – I meant to write “This is akin to more political powers being exercised over the UK people today, by the EU, with the agreement of the establishment (akin to the Royal Court of old).

History can be troublesome. Having dispatched Charles I, the English then dispatched the Catholic James II, though not quite so literally. James’s last stand, as it were, was at the Boyne, when he faced the protestant King Billy. And Billy was supported by, er, the Pope.

If you extend that idea. then Parliament took power. Theresa May is more akin the Charles with her divine right to personally choose red lines for Brexit and taking back powers of law making from Parliament. If Parliament were really to take control, not Party Politics, we might very well be in for a period of innovation.

If you extend that idea. then Parliament took power. Theresa May is more akin the Charles with her divine right to personally choose red lines for Brexit and taking back powers of law making from Parliament. If Parliament were really to take control, not Party Politics, we might very well be in for a period of innovation.

Our school text books telling us that a civil war that involved Wales was the ‘English’ Civil War was one of those things that drove teenage Welsh Nationalism when I was at school.

Alas for our leftist tradition, Christopher Hill et al, it also follows, vide the exhibition of his collection at the RA, that Charles 1 was the last non Brexit leader, oh irony, and Cromwell an old model Corbyn, if much more generous on immigration.

I live in the county of Ceredigion, a county that voted REMAIN by 10% (55% to 45%). I am also interested in the English Civil War as I have decided to take my interest in living history and apply it to the life of a fictional Welshman called Henry Cardigan who becomes Henri de Ceredigion, a member of the King’s Musketeers of France, in order to prevent the dalliances between the Duke of Buckingham and Queen Anne from becoming public knowledge in France and is therefore firmly in the Royalist camp.

If, as Stefan suggests, we are entering a new Civil War, then I would not honestly know which camp to be in, as I voted REMAIN but just want Brexit over and done with so that we can talk about slightly more important things in life such as the chronic underfunding of the NHS, the re-establishment of power sharing government in Northern Ireland and perhaps most important of all, tax evasion.

Hi Harry. I live in Cambridge City, where Oliver Cromwell was educated. He lived in nearby Ely and we count ourselves firmly in the Parliament camp. Cambridge City centre had the ward with the highest remain vote in the country 88.8% and South Cambridgeshire also bucked the national trend for a rural county voting remain.

I understand people’s impatience with Brexit, but the only short Brexit is no Brexit. It will take a huge amount of time, a huge amount of manpower and a huge amount of money todo. And if we give way on most of Theresa May’s red lines, we may just end up not very much worse than we are now. However, that is not how it’s going.

For now, Brexit is the most important thing facing our country. Until we know where we are going and if we can get there, everything else is on the back burner. The crisis in the NHS, education, prisons, probation services, etc etc will have to wait. If we just exited Brexit and agreed to stay in the EU, then we could finally tackle the real problems in the country, none of which have been caused or even exacerbated by our membership of the EU. Then we could forget all about it.

“The political map of the Brexit vote resembles the regional distribution of support for the King, Court and Tories against Parliament, Merchants and liberal Whigs. “

It also represents university towns versus the rest, university towns being pro-remain either because they’re happy with the status quo or because they’re unblooded students who fear the new compounded by being under the tutelage of those who are doing very nicely thank you very much courtesy of EU finding. Meanwhile the rest of the country is pro-leave because they’re not so secure and unhappy with the Westminster and Brussels bureaucracies.

An interesting comparison to make!

On the History side I think the blog is a little weak. Remember the Whigs and Tories didn’t exist during the Civil War, ‘political parties’ as we know them today did not develop until later in the seventeenth century.

Also I’m rather skeptical as to whether the post-Civil War settlement can usefully be described as ‘free’. Yes, people were not subject to a monarch, but the successive regimes were based on a limited franchise and hinged on the political support of the army and Cromwell, whose time as Lord Protector could fairly be described as a sort of early modern benevolent dictatorship.

Something else to bear in mind is that individuals’ political preference was only one factor which impacted upon side-taking. Also highly important was a tendency to conform with others in a locality, in order to avoid reprisals, as well as a sense of duty in which irrespective of one’s own preference, an individual was obligated to follow their kith, kin or patron.

This being said I think the maps do bear a cursory resemblance to one another. The principal reason for this is in my opinion is that the location of England’s large urban clusters by and large have not changed since the seventeenth century, and that the cosmopolitanism of such areas both de-emphasizes the importance of feudal notions of hierarchy (the Civil War) and facilitates acceptance of ‘the other’ (the EU referendum).

“Scotland and Ireland have saved England from itself in the 17th century. It may well turn out, once again, that Scotland and Ireland will keep Britain open and defeat little England.”

I resent the idea that Scottish and Irish nationalism = good, and English nationalism = bad.

The basic premise of the article is wrong: namely that the referendum was a choice between narrow conservatism and open minded liberalism.

I am a classical liberal, a moderate libertarian. Therefore I voted Brexit, as I believe in free world trade, not in a social-democratic protectionist bloc called EU.

This (wrong) basic premise is typical remainiac stereotyping.

The problem with unilaterally attempting free world trade is that you can cut you import duties, but this doesn’t make anyone else do so. So your uncompetitive industries get out competed, and your competitive ones can’t grow because of other people’s tariffs.

It also doesn’t help with the biggest issue with international trade, which is different standards. Fixing which seems to be the second thing that annoys most Brexiteers.

@JP Floru. Several other commenters, including myself, were also slow to appreciate the tongue-in-cheek nature of this article.

For ‘corroboration’ see my article of 2016: https://kjohnsonnz.blogspot.co.nz/2016/06/the-second-english-civil-war-2016-round.html

I do believe Brexit and the falior of our leaders to deliver it for the people will usher in a second civil war in this country,the historical comparison with the English civil war is a strong one because actually it is the same issue at steak,in 1642 it was King at odds with Parliament in 2019 it’s parliament at odds with the people there is i believe an interesting parallel to be drawn to the American civil war and it’s cause in that war you had a southern population who firmly believed it’s culture identity and way of life was about to be destroyed by a liberal North,in modern England it’s reversed a northern population feeling it’s values and identity are being disregarded by a liberal South.Let the Nations divisions be tried by blood.

An industrial revolution happened between the 1640s and Brexit, which should have altered the map completely. But, one might argue, that places that are now post-industrial have reverted to their original status of being outside the economic mainstream and that the central thesis still holds true. I currently do a lot of work in Yugoslavia, I am, therefore, not at all confident that England will keep the peace over Brexit. We should pay close attention to these kind of theories, we may need to try and understand better what happened in the 2020s.

Not sure what point the article is making – surely in the end the monarchy was restored – which would seem to put the Brexiteers ultimately on the winning not losing side using the comparative model in the article

All irrelevant. Once the ice melts, the methane trapped in permafrost is released and the global warming tipping point has been passed it will only be a question of time, and not much of it, before Europe is a heap of ash. Whether Great Britain is part of that heap or a separate smaller heap won’t matter very much. Global warming (as the name suggests) is global, and the only issue regarding Brexit is whether we can do more to arrest it in the short time available as part of a strong reformed European Union in which we play a leading role (not whingeing about opt outs and refunds) or as a bunch of selfish, small minded half witted nationalists with our collective head stuck in the sand.