Two years after the vote, there is little certainty regarding the UK’s political and economic future. Brexiters themselves are split between wanting a Singapore-on-Thames or a Belarus-on-Trent. Simon Hix (LSE) assesses where the UK-EU relationship is heading. He argues that despite persisting uncertainty, a No Deal is the least-preferred option of both the UK or the EU27, and hence the least likely. He suggests that some sort of agreement will be reached before March 2019.

Two years after the vote, there is little certainty regarding the UK’s political and economic future. Brexiters themselves are split between wanting a Singapore-on-Thames or a Belarus-on-Trent. Simon Hix (LSE) assesses where the UK-EU relationship is heading. He argues that despite persisting uncertainty, a No Deal is the least-preferred option of both the UK or the EU27, and hence the least likely. He suggests that some sort of agreement will be reached before March 2019.

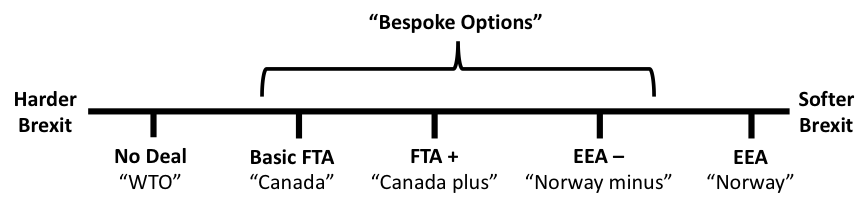

While there has been much debate about the Brexit “withdrawal agreement” and the transition arrangements there has been less discussion of the longer-term “future relationship” between the UK and the EU27. The choice between a “Hard” or “Soft” Brexit has been known for some time, but the options are better characterised as a continuum rather than a dichotomy.

No Deal – leaving the EU without a deal, and trading as a World Trade Organization member.

Basic FTA – EU-UK free trade agreement (FTA) similar to the EU agreements with Canada, South Korea and Japan, which mainly cover trade in goods but contain very little on services.

FTA+ – an FTA which includes an agreement on financial services, such as “mutual recognition” of regulatory standards, a “regulatory equivalence” agreement, or the UK applying EU regulations and EU Court jurisdiction in return for access.

EEA- – the UK remains in the European Economic Area (EEA) but secures some opt-outs, in particular on the free movement of people (such as a cap on the number of EU migrants registering to work each month or an “emergency brake”).

EEA – the UK remains in the EEA, so stays in the single market (the free movement of goods, services, capital and persons, EU rules, and EU Court jurisdiction) and pays into the EU budget, but leaves the customs union (to sign FTAs with third countries) and gains control of fisheries and agriculture.

The key question, then, is which of these options do the UK and the EU27 prefer independently and jointly? To answer this, let’s consider the economic and political interests of the two sides.

Starting with economics, the “harder” the Brexit, the bigger the likely economic impact to both the UK and EU27, as a result of the loss of trade due to new physical, fiscal or regulatory barriers. The UK would save in terms of its payments to the EU and could claim back some of the losses in EU trade with new trade agreements with third countries. But, standard trade “gravity” models suggest that agreements with countries that are further away are unlikely to compensate for any loss of trade with the EU. As a result, in the UK government’s leaked cross-Whitehall report, HM Treasury estimated that a No Deal outcome would reduce UK GDP by 8% over 15 years (relative to current trend growth), a free trade agreement along the lines of the EU-Canada agreement would reduce GDP by 5% over the same period, and the EEA option would lower GDP by 2%.

The EU is unlikely to be hit as hard as the UK. In 2016, the EU27 constituted 43% of UK exports in goods and services, while the UK constituted only 16% of EU exports in goods and services, and total UK trade with the EU27 (exports plus imports) constituted 12% of UK GDP while total EU27 trade to the UK constituted only 3-4% of EU27 GDP. As a result, analysis from the EU’s side suggests that an EEA outcome would only cost the EU27 approximately 0.1% of GDP by 2030, a basic FTA would mean a loss of 0.3-0.6% of GDP, and a No Deal outcome would cost 0.3-0.8% of GDP.

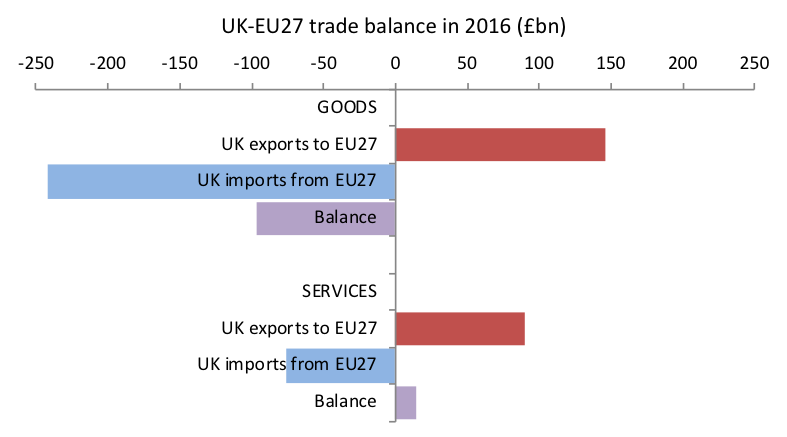

The content of the trade between the UK and EU27 is also asymmetric, as the following figure shows. In 2016 there was an overall trade deficit between the UK and the EU27 of £80 billion. Also, whereas there was a large UK to EU27 trade deficit in goods (of £96 billion) there was a trade surplus in services (of £14 billion).

This trade asymmetry has strategic implications for the negotiations. Both sides have an interest in securing a trade agreement, and any reduction in imports or exports will have negative implications for consumers and businesses in the UK and EU27. Nevertheless, at the aggregate level, which is what politicians tend to focus on, the sectoral balance of trade suggests that the EU27 are more eager to want a deal that secures as frictionless trade as possible for goods yet will be less eager than the UK for a deal that includes free trade in services.

Image by Paul Bissegger, CC Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International.

Image by Paul Bissegger, CC Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International.

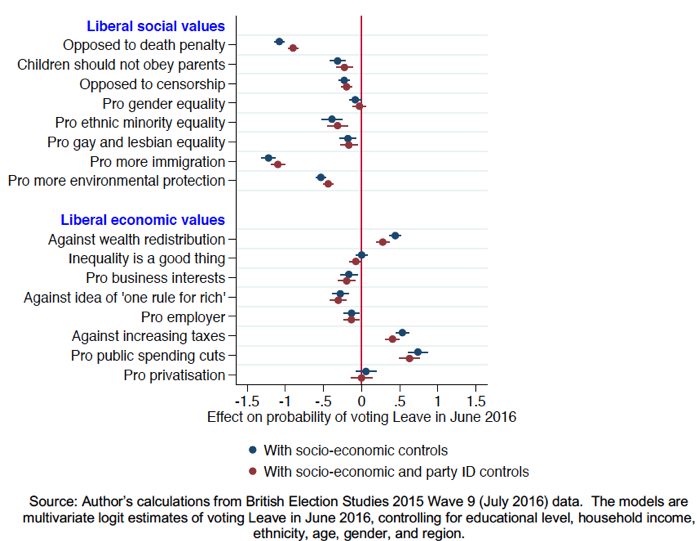

The negotiations will also be shaped by politics, of course. As many commentators have noted, the referendum outcome on 23 June 2016 was driven more by cultural and ideological values than by economic interests. The “project fear” message of the Remain campaign, which emphasised the economic costs of Brexit, was trumped by the “take back control” message of the official Leave campaign and the explicitly nationalist message of the unofficial Leave.EU campaign.

Mirroring the two Leave campaigns, there are now two competing narratives about a post-Brexit Britain. The so-called “liberal leavers” present “Singapore-on-Thames” vision: regaining sovereignty to deregulate the economy, abolishing “Brussels red tape”, pursuing a liberal immigration policy, signing free trade agreements with partners across the world, and even unilaterally cutting tariffs and quotas on imports. This narrative is often associated with libertarian think-tanks like the Adam Smith Institute, Economists for Free Trade, Legatum Institute, Institute of Economic Affairs, and Initiative for Free Trade.

The problem for these “liberal leavers” is that most Leave voters actually prefer a “Belarus-on-Trent” vision of Britain: more socially conservative and more economically protectionist. For example, the above figure shows the relationship between liberal social and economic values and the probability of someone voting to Leave the EU. Every “socially liberal” value in the survey is negatively correlated with voting to Leave the EU, and Leave voters do not have clearly “liberal” economic values. Indeed, following their own survey of public attitudes, the Legatum Institute reluctantly conceded that the British public post-Brexit generally supports higher taxes, more public spending, nationalisation of key industries, and more regulation of markets and labour markets in particular.

The EU27 also have some key political interests. In particular, the EU27 does not want to undermine the integrity of the four freedoms (of goods, services, capital, and persons) in the single market. One aspect of this “no cherry-picking” line relates to the current agreements the EU has with third countries. Any special arrangement for the UK, for example for financial services access, would lead Switzerland, South Korea, Canada, and others to demand similar arrangements, under the WTO Most-Favoured-Nation rules.

A second aspect relates to the potential unravelling of the EU itself, driven by a fear of Brexit contagion. Support for anti-EU populist parties has grown in a large number of member states since the mid-2000s. Regardless of how painful the process of Brexit will be for the UK, once the UK is out the other side, there will be a new exit model: a “British model”. This model might be attractive to several countries who, like the UK, are not members of the Euro nor support deeper political integration, especially if the new “British model” means considerable access to the EU single market, a special customs relationship, and some control on the free movement of people.

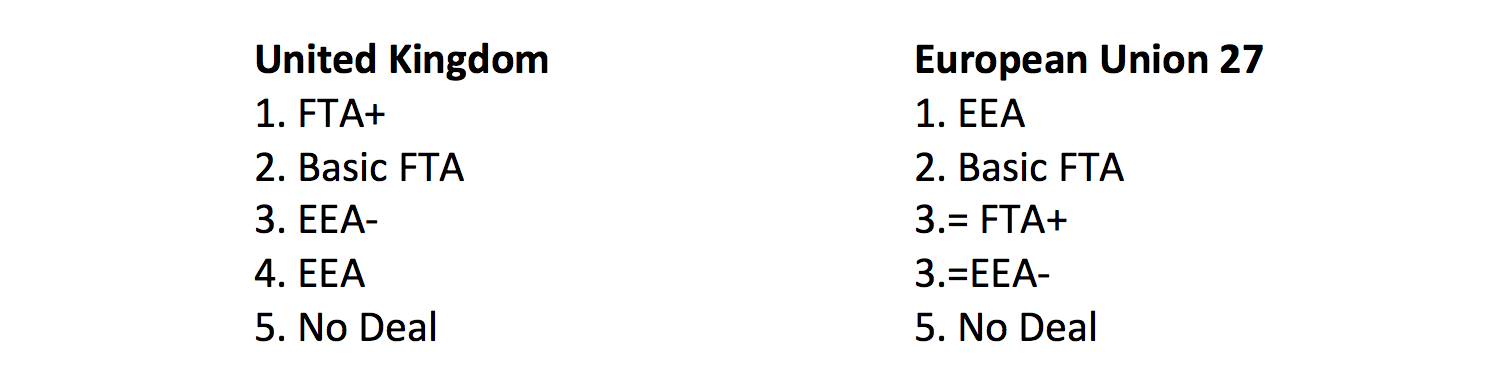

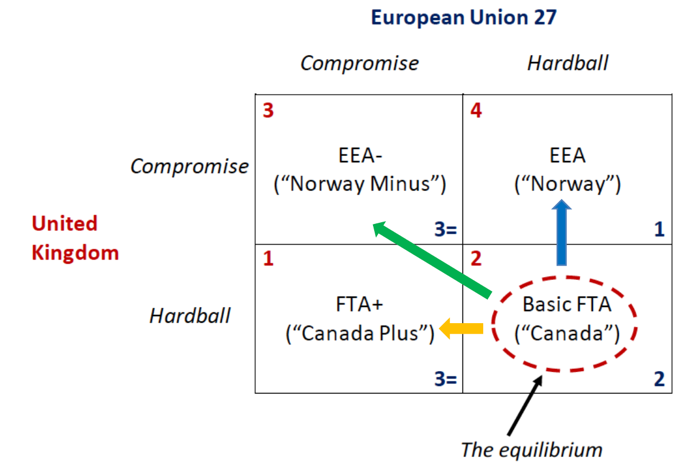

This discussion suggests the following rank-ordering of the options by the UK and EU27:

From the UK’s side, on the assumption that political interests – and particularly the “red-lines” on sovereignty and ending the free movement of people – over-ride economic interests, the FTA+ and FTA options outweigh the EEA- and EEA options. Meanwhile, from the EU27’s side, the two most preferred outcomes, in terms of maintaining the integrity of the single market, are the EEA and a Basic FTA, whereas the EU is largely indifferent between the FTA+ and EEA- options, as either would involve a potentially dangerous precedent. Encouragingly, though, No Deal is the least-preferred option of both the UK or the EU27, which suggests that some sort of agreement will be reached.

These preference-orderings produce the following bargaining situation:

There is only one equilibrium in this game: a Basic FTA. The EU27 would play “hardball” because they prefer an EEA or a Basic FTA to any other outcome. The UK’s “best response” to this strategy would be to also play hardball, as they prefer a Basic FTA to the EEA. Furthermore, neither the EU27 nor the UK have an incentive to deviate from this equilibrium; so neither side has an incentive to “compromise”.

This does not mean that other outcomes are not possible. In fact, this analysis helps us focus on what would have to change for a different outcome to emerge. For example, for an FTA+ rather than a Basic FTA (as indicated by the orange arrow), the EU27 would need to compromise, to allow UK “cherry-picking”. Alternatively, for the final outcome to be the EEA rather than a Basic FTA (as indicated by the blue arrow), UK domestic politics would have to shift, so that the “red lines” on ECJ jurisdiction, adhering to EU regulatory rules, and the continued free movement of people are removed. This is unlikely given the preferences of Theresa May, the composition of the UK Cabinet, or the views of the majority in the House of Commons. Nevertheless, these preferences could change, for example, if public attitudes on the free movement of people change, or if there is a sudden and significant economic shock that shifts Conservative MPs’ views about staying in the single market.

Then, for an EEA- rather than a basic FTA (as shown by the green arrow), the EU would need to allow UK “cherry-picking” and UK domestic politics would need to shift to remove the key red lines.

Finally, even if the preferences of the UK or the EU27 change, a further limitation is the ratification hurdle for the final agreement: unanimity in the Council and ratification in more than 30 national and regional parliaments. Every “veto player” would need to prefer the same alternative to a Basic FTA for a different deal to emerge. And, there will be not much time to agree and ratifying an agreement: between March 2019 and the end of the transition period at the end of December 2020.

I have tried to focus on is how political bargaining over the final Brexit deal might play out, based on underlying economic and political interests. This analysis suggests we are heading for a basic free trade agreement, which includes zero tariffs and quotas on goods and some special customs arrangements, but with not much on services trade.

It will be difficult to agree the “plus” part of a free trade agreement on financial services. The EU27 would suffer an economic hit if there are limitations on the access of financial service providers in the City of London to the single market. However, the economic impact for the EU27 would be much smaller than for the UK. In the medium-term, large parts of the UK financial services industry could move to Frankfurt, Paris, Dublin, Amsterdam and Luxembourg. And, the political cost for the EU27 of compromising in this area could damage the integrity of the internal regulatory and mutual recognition frameworks of the single market, which the EU seems determined to avoid.

On top of all that, the negotiating time will be short and the ratification hurdles will be high. Put another way, now is not the time to propose to the Wallonia parliament or the French National Assembly a trade agreement that gives City of London bankers easy access to the single market, without the UK applying EU rules or being subject to ECJ jurisdiction.

This is a summary of the Annual Lecture of the Journal of Common Market Studies. The full text of the lecture is available online. This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of LSE Brexit, nor of the London School of Economics.

Simon Hix is the Harold Laski Professor of Political Science at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

There is something not looked at in the article which is that FTA+ and EEA- are not options the EU can give. The reason is that if the EU gives the UK and FTA+ style agreement it is bound by its other FTAs with Canada, Japan and Singapore to extend the same privileges granted in the FTA+ style agreement to the UK to those countries as well. So Japan, Singapore, Canada, etc will then also get financial services included in their FTAs. The EU can’t reasonably offer this.

As for EEA-, any emergency break or limits on the registration of EU nationals coming to work would likewise need to be extended to the EFTA/EEA partners and basically bring an end to the EEA’s single market.

The only realistic options are: 1. No Deal – WTO; 2. Basic FTA – Canada; 3. DCFTA – Ukraine, 4. EEA (no deviations) and 5. shadow EEA + customs union or BINO – single market plus customs union (basically EU membership without voting rights).

The UK doesn’t want options 4 and 5 or 2 or 1. The EU doesn’t really want option 1 but can work with any other option once Northern Ireland remains in customs union and single market with the Republic of Ireland. This really only leaves option 3 but with the provisio that NI must remain in a customs union and the single market with Ireland. The UK won’t agree with that. Hence option 1 (No Deal) seems the most likely to happen by default despite both sides finding it the least desirable outcome.

I agree with Hunter – for the reasons he gives, No Deal is the only logical outcome.

However, unless the UK is on a suicide mission to become a Third World country following the sudden and violent changes an overnight exit would bring, any government of the day will have to ask for an extension period – i.e. the can will have to be kicked down the road and possibly more than once.

Once the can is far enough down the road, a future government is very likely to go to the country yet again with a new referendum and this asinine debate can start all over again! Perhaps a future electorate will come to a different conclusion.

I feel like a layman in such expert company but I would at least question one assumption: if there is no deal on services, “large parts of the UK financial services industry could move to Frankfurt, Paris, Dublin, Amsterdam and Luxembourg.” I don’t think it’s that easy to move a large chunk of London’s services abroad. More likely, surely, is that companies will move the minimum, such as trading desks and front-office, where required by law, but leave the rest in the UK. If the EU tries to impose banking 100% made-in-EU they will find little enthusiasm for this among businesses, as there is already a lot of cooperation with, for example, New York.

Also many service sectors may be hardly effected. If a US company is looking for an agency to coordinate a European advertising campaign, I guess it might well choose one based in the UK. Does Brexit make any difference to this?

So I guess an agreement on services is not that critical and that means we will end up with something like Basic FTA.

As I say I am not an expert so please explain to me in simple language why I am wrong.

@Anonymous the thing with a basic FTA is that it will effectively split the UK off from the Single Market in services, much more so than for goods. The city is probable big enough and has deep enough pockets to do fine for the time being, but the UKs service export is much more varied than being dominated by financial services (see here https://www.ons.gov.uk/businessindustryandtrade/internationaltrade/bulletins/internationaltradeinservices/2016). A basic FTA would most likely put up significant barriers for most service exports to the EU and one would expect a decline in service exports. At that point the UK will have the same level of market access to the Single Market as Canada, so why would you pick a UK company that’s outside the Single Market to run an advertising campaing for the Single Market? But as the last few days have shown I don’t think there is a majority for a FTA in the HoC anyway as that would involve coming to terms with the Irish question.

Hi Christoph,

Thanks for your reply.

“At that point the UK will have the same level of market access to the Single Market as Canada, so why would you pick a UK company that’s outside the Single Market to run an advertising campaign for the Single Market?” I actually said European (which includes the UK, in or out of the EU). Why would even a hard Brexit make any difference? Are there taxation reasons or what? Someone please tell me.

Why not pick a Canadian agency to coordinate a European campaign? Maybe geographical reasons (time zones and flight times would be a nuisance) and social (a European agency is more likely to have access to European culture or cultures than a Canadian one). Is the Single Market a factor at all?

Hi Anonymous,

I am not an economist by training and I just did a very short literature review for publicly available resources (no point in quoting someone behind a 40$ pay wall), so take everything I say with a grain of salt but according to Mustilli and Pelkmans 2013 (https://www.ceps.eu/system/files/Access%20Barriers%20to%20Services%20Markets.pdf) there are four broad categories of barriers to trade in services under WTO rules: a) Quotas, local

content, prohibitions b) Price-based instruments such as visa fees and price regulation c) standards, licensing, and public procurement and d) discriminatory access to distribution

networks which is probably the most important for our advertising agency example.

So in the case of the advertisement agency, it might very well be the case that UK agencies would only have sub-par access to the Single Market distribution networks. That’s why you would probably want an UK agency to run your UK campaign and another one to run your campaign within the Single Market. And then another one to run your campaign in, let’s say Russia. In that view there is not really a European market for services, there is the Single Market and a few other national markets.

I mean there should eventually be a new equilibrium once the trade in services has shifted to take the new trading barriers into account.

Hi Christoph,

I am also not an economist and have nothing to do professionally with either advertising or the WTO, but my interpretation of the following is that the EU is committed to not discriminating against any other WTO member when it comes to advertising across borders.

http://i-tip.wto.org/services/GATS_Detail.aspx/?id=23125§or_path=0000100018

Would you agree?

By the way I didn’t know about this when I picked the example of advertising, which Christoph has kindly followed. If anyone would like to discuss the effect of a hard Brexit on other service industries, please don’t let me stop them.

Hi Christoph,

sorry, the link I gave to the WTO website doesn’t work. I think it is using cookies. I don’t know how to get a corresponding permanent link.

I went to

http://i-tip.wto.org/services/Search.aspx

and entered the European Union into the “Members” part and ‘”advertising” into the text search, to get the page I referred to.

I get

– 1 BUSINESS SERVICES

Mode of Supply : 1) Cross-border supply 2) Consumption Abroad 3) Commercial presence 4) Presence of natural persons

European Union (partner code)

1 BUSINESS SERVICES

1.F Other Business Services

a) Advertising

(CPC 871)

Limitations on Market Access Limitations on National Treatment

1) None 1) None

2) None 2) None

3) None 3) None

I’ve omitted 4) (“Presence of natural persons”) as there are restrictions there and I don’t think they are so relevant to this discussion.

Hi Anonymous,

Did you mean this link http://i-tip.wto.org/services/DetailView.aspx/?cid=C899§or_path=0000100018? For whatever reason the one you posted didn’t work, but you still have the horizontal overarching limitations, but admittedly those do not look too onerous for advertising. So I concur, in case of advertising you are probably right and the effect of relying on GATS would not be too bad for the UK.

I also looked at a few other sectors within the EU’s GATS commitments and while financial services has a bunch of restriction, the picture looks much better for professional services.

One interesting thing to figure out would be how discriminatory laws can be without running foul of the GATS commitments and how burdensome it is for a service oriented company to comply with the different GATS limitations of the different member states.

Hi Christoph,

Thanks, that’s the one. Thanks also for the additional research.

As for the last paragraph, maybe it would be interesting to figure that out, but I lack the qualifications. My gut feeling is that while the whole Brexit thing will be incredibly bothersome for companies in the service sector who do business in both the EU27 and the UK, there are not going to be many parts of the UK services industry which will be forced by Brexit to move lock stock and barrel to Frankfurt or anywhere else. I suppose such service industries are largely about information processing, which makes it very difficult to impose border controls. And all multinationals will be expert at setting up complicated shell company structures to dodge tax obligations, so they should be able to do the same to dodge any restrictions on service providers the EU27 may try to impose.

So in essence Brexit will be most burdensome for the small service businesses that either lack the manpower or resources to adapt to the new regime. Thanks for all your research as well; especially for digging out and correcting me on the WTO/GATS implications of a FTA-style hard Brexit.

How can Mr Hix make no mention of Ireland!? How can there possibly be a “basic free trade agreement” while avoiding a hard border, especially as it is now illegal for Northern Ireland to be in different customs territory from rest of UK. There is absolutely no possibility of there being a “basic free trade agreement”.